Robotics Rebuilds Manufacturing Landscape

By Josh Medore

YOUNGSTOWN, Ohio — With the press of a button, a plasma torch swings into place. With another press, a protective screen slides down to shield the shop floor at Hickey Metal Fabrication from sparks. And, with a third touch, the torch trims the ends off 20 eye pins.

At the end of the couple of minutes it takes to do all this, the pins are trimmed to the length the customer of Hickey wants.

“This used to all be cut by hand,” says Vice President of Operations Adam Hickey as he shows the result. “It’d be maybe one or two at a time.”

The movements of the torch, from a resting position to a ready position to the line it moves along as it cuts the pins, are all preprogrammed. It’s just one of robots Hickey Metal Fab uses on its shop floor in Salem.

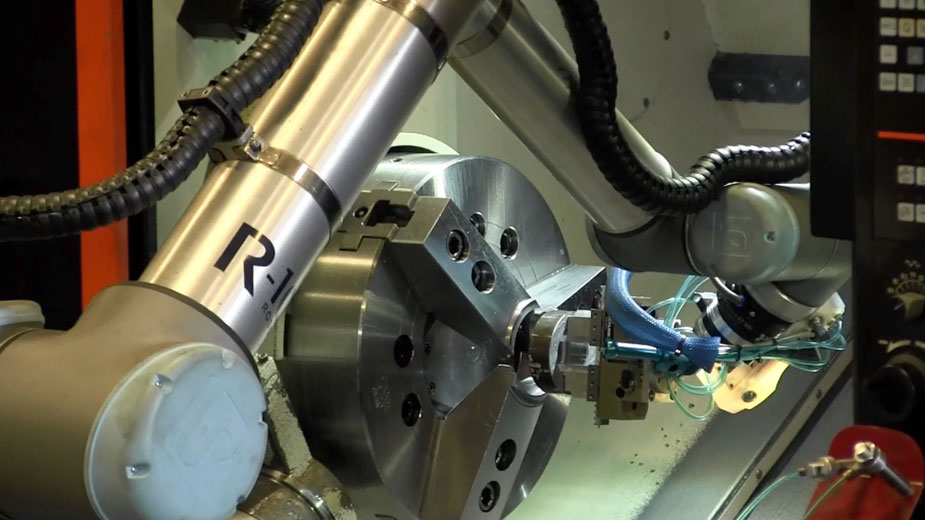

Elsewhere, there’s a machine with the sole task to load metal discs into a lathe, wait for the disc to be trimmed and then remove it before placing the part into a crate.

Another machine, one that’s still being set up, will weld brackets onto a customized metal plate. Yet another, one that hasn’t been installed yet, will be fully automated. All the operator will have to do is load materials into the machine. The robot, manufactured by Trumpf, will then cut the parts, remove them from the sheet of material and load the parts onto a palette, ready for it to be shipped out.

Taylor Winfield Technologies projects range from this seven-cell system to a machine for spot welding cookie cutters, says Blake Rhein.

“There’s equipment out there that is truly automated where a person doesn’t touch a part until it’s done,” Hickey says. “We really don’t need a guy standing there all day putting a part in and out [of a lathe]. I’d rather use him on something that requires experience on something a robot couldn’t do.”

Adds Secretary-Treasurer Suzanne Hickey: “Some people have the misconception that robots put people out of work. What we’re trying to do is automate a process for the high-volume stuff and give the complicated stuff to an employee. They’re intelligent. We can put them on a job that’s more complicated.”

The metal shop in Salem started using its first robot in 2004, says President Leo Hickey, and now has around 10, either in use or in the planning phase. The adoption of robotics by Hickey Metal Fab is by no means an outlier in the manufacturing industry.

The International Federation of Robotics estimated the number of robots in use worldwide was 1.83 million in 2016.

That number, the organization said in its 2017 executive summary, is expected to reach 3.05 million by 2020. In North and South America, the number of industrial robots sold has risen every year since 2009 except for a slight dip in 2012, including 41,000 sold in 2016.

The skyrocketing rate of adoption is “the confluence of a lot of factors,” says Jay Douglass, chief operating officer for the Advanced Robotics for Manufacturing Institute in Pittsburgh.

“Among the economic factors is that hardware, software and implementation is getting cheaper. Technologically, robots are reaching new levels of functionality with vision, perception and manipulation,” Douglass continues. “The social factor is that the economy is reaching full employment. In the area of advanced manufacturing, there’s a big skills gap.”

The purpose of the institute is to develop solutions to close that gap through training programs such as apprenticeships, as well as research into new applications of robotics.

Every manufacturing robot requires some computer skills because operators must be able to adjust the programming of a robot. But that doesn’t eliminate the need for the traditional machine shop skills, says Leo Hickey.

“Computer skills are important. What I like is a guy that knows welding because he knows what kind of joint he wants and he knows where he wants to position the torch,” he says.

At Hickey Metal Fab, George Firth operates a robot that cuts the tips of eye pins.

At Hickey Metal Fab, George Firth operates a robot that cuts the tips of eye pins.

Welding is among the tasks the industrial robots are best suited. The process is easily repeatable because the robot can weld the same spot on a sequence of parts over and over and over again, not faltering on position or quality as long as everything is in place and the machine is maintained properly.

“We apply them to tasks that have repeatability, sort of mundane types of tasks,” says Marty Linn, principal robotics engineer at General Motors Co. “Over the years, there have been all kinds of attempts to use robots for exotic applications. But understanding what robots really do well – repetitive tasks – has been the sweet spot.”

Worldwide, GM factories use roughly 34,000 robots through every step of the manufacturing process, from the foundries where parts are produced to the final assembly at places such as its Lordstown Complex.

GM has used industrial robots since 1961 when one was added to the line at the Ternstedt Plant in Trenton, New Jersey, making the company first in the industry to use robotics.

What robots are capable of is largely a function of money and time, says Blake Rhein, vice president of sales and marketing for Taylor Winfield Technologies in Austintown. If a company is working with an unlimited research and development budget and has a long enough timetable, then anything is possible. But that’s rarely the case.

“Robots run the gamut from micro-processing robots all the way to machines that are lifting truck frames and spinning them around,” he says. “What customers are after is repeatability, better quality, a higher output and labor cost reduction.”

Taylor Winfield is an integrator, working between robot manufacturers – the primary three the company works with are Yaksawa, Fanuc and Kawasaki – and industrial companies.

While the manufacturers develop their robots and end-of-arm tools for them, it’s companies such as Taylor Winfield that work out the processes, positioning and programming.

The Austintown company’s projects have ranged from those as small as an automated process for spot welding on cookie cutters to one as large as a seven-station setup that manufactures parts.

“We create a whole cell. We test it. Customers send parts in to us and we’ll do a runoff. They’re looking for the exact placement of a part, the cycle time, the repeatability,” Rhein says. “Then, all the equipment ships to their factory. We send test and service guys to commission the equipment on-site.”

With Taylor Winfield, customers often approach the design firm with a task that they need automated and allow the company to find the appropriate machines and design the cells. That’s not the only route, however.

Hickey Metal Fab has found machines through trade shows and journals and also discovered pieces that it has explored adding. In that setting, there’s always a bit of extrapolation needed to determine if it’s the right fit, says Nick Peters, a vice president and engineer with Hickey.

A new addition at Hickey Metal Fab is a material-handling robot, says Nick Peters.

A new addition at Hickey Metal Fab is a material-handling robot, says Nick Peters.

“You can see it in a [show] setting but you also have to think about how someone uses it,” he says. “There’s always a learning curve and figuring out the little details you didn’t expect. There are things that guys may be doing to make the process smoother that you don’t know about. Now, you have to find a way to automate that process.”

Among the technological advancements in industrial robotics is the streamlining of programming. It’s still complex, but is more accessible.

The machine at Hickey that loads a lathe, for example, has a screen that displays the steps of the process in order, from pauses to turns to the adjustment on its clamps. Steps can be added, removed or adjusted through the touchscreen. To learn to use the machine, operators are sent to training programs offered by the machine makers, says Suzanne Hickey.

“There’s always training. With new equipment, they give you options for different levels of training, say operation or programming or maintenance,” she says. “When we get new equipment, we get a couple parts that we want on there and programmed, to get the guy running it familiar. Then, we send them to school for the training.”

At Taylor Winfield, a team of electrical engineers handles the programming of machines as well as the addition of software that allows them access to the machines should a problem arise after it’s been installed.

“They are extremely customized, to the point that you can’t just take them out of the box, plug them in and expect them to do what they’re supposed to,” says Katie Denno, marketing manager. “We don’t have to travel 3,000 miles to diagnose their machine. Customer uptime is critical. If they’re down, they aren’t making parts.”

Feedback from machines will play an increasingly larger role in the future of robotics, Rhein adds, allowing companies to centralize some operations such as quality control.

“One of our core focuses is the integration of welding and manufacturing with the internet of things, data feedback,” Rhein says. “Robots will be able to report back on what they’re doing, verify that a process is complete, that tolerances were met.”

At General Motors, the future of robotics is in collaborative machines that work alongside employees. One such endeavor, IronHand, is being done with Bioservo Technologies. The machine is a glove fitted with a small, battery-powered robotic system that aids workers in gripping materials.

“We’re very interested in advanced manufacturing technologies that keeps workers safe and helps us deliver quality vehicles,” GM’s Linn says. “There are all kinds of technologies, like collaborative robots, and we’re working hard to use wearable robots that help workers do ergonomically challenging tasks better.”

For smaller companies, the Advanced Robotics for Manufacturing Institute’s Douglass says robotics are trending toward affordability.

“It’s not just about what the robot can do. It’s about how you integrate it into your operation. Do you have to shut down for a month to install the thing? Well, most small companies can’t shut down for a day without taking a hit,” he says.

“You’re going to see more robots at smaller companies because robots are smaller and cheaper, plus they can be repurposed.”

Copyright 2024 The Business Journal, Youngstown, Ohio.