Rock Photographer’s Classic Shots at the Butler

YOUNGSTOWN, Ohio — Larry Hulst would bring his camera to rock concerts so that he would have photos to keep as personal souvenirs.

Over a 30-year span beginning in 1970, he shot just about every great act, from Jimi Hendrix to Van Halen.

His hobby eventually turned into a side job, and then a career as a photographer for the US. Air Force Academy in Colorado Springs, Colo. But those photos of rock stars remained his most appealing body of work.

In recent years, a part of his collection of rock concert photos – shot with high-contrast black and white film – has been touring museums as a traveling exhibition titled “Front Row Center: Icons of Rock, Blues and Soul.”

Youngstown audiences can check it out beginning April 6. The 70-piece show will go on display that day at The Butler Institute of American Art, and will run through June 27.

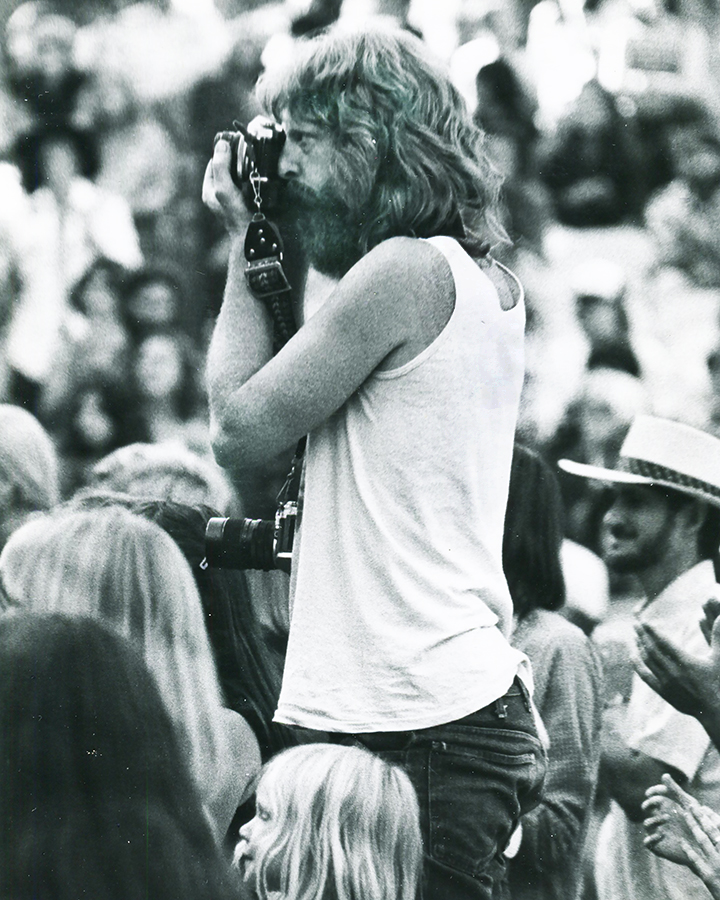

Hulst’s photos, which include Pete Townshend, Janis Joplin, Tom Petty, Muddy Waters and many others, are all tightly focused on the musicians. He wasn’t interested in what was going on elsewhere on the stage or in the arena.

During a phone interview from his home in Colorado, Hulst talked about the circumstances that shaped his work.

It all started in 1969 when the then-Navy corpsman returned home to Sacramento, Calif., after completing a tour of duty in Vietnam. Rock music was his passion and he started attending a lot of concerts at The Fillmore in San Francisco.

“I went in as a fan and took photos, the same as any person in the audience today with a phone,” Hulst said. “I wanted a picture for myself to remember the show, as opposed to buying a T-shirt.”

Bringing a camera to a concert has been taboo for years but there was no rule against it in those days. There wasn’t even a problem selling photos outside the building, although Hulst did get told to desist if he was actually on the Fillmore property.

Hulst would sell his photos before and after concerts for $1 to $3 apiece. His break came in 1973 when he sold a photo of Muddy Walters to Rolling Stone magazine. “That motivated me to get more published,” he said.

He began working with a photo agency that was able to sell more of his work to publications.

Up until then, the 6-foot-5 Hulst never bothered to secure a photo pass. He would shoot from the seats or standing area in front of the stage, getting as close as possible.

“It was easier to buy a ticket than to get a photo pass back then,” he said, explaining the passes were in high demand and usually required him to prove he had been hired by a publication to shoot the concert.

After he started getting published, Hulst had an easier time getting passes to shoot from the photo pit in front of the stage. He also had no interest in going backstage before or after concerts; his focus was always on the stars on the stage.

His photos are action closeups that show the artists and nothing else. It’s a style he learned from his greatest influence, Jim Marshall, who was a leading rock photographer of that era.

“When I did my studies of great photographers and how they approached concerts, it was always Jim Marshall, and it was always to emphasize the artist, as a portrait,” he said.

Another reason for his tight shots is that there wasn’t a wide choice of lenses back then. Because he was shooting from the floor, Hulst generally just carried a 135mm lens.

“I’m standing 15 to 18 feet back from the stage, which was maybe six feet tall, and I’m 6 foot 5, so I had an elevation angle that was better than most photographers.” he said. Hulst never bothered to even bring a wide-angle lens to a show. “I saw no reason to,” he said.

As to why he only used black and white film, again it was mostly due to the circumstances of the era.

“When I first started out, I was told that to get your work into a museum, color wasn’t an acceptable medium,” Hulst said. “Most of what was on the walls at museums were in black and white.”

Hulst did also use color film at concerts, but only submitted black and white photos because they tended to reproduce better in print. Most magazines at the time, he said, mainly purchased black and white photos.

“Back then, stage lighting was bad,” he explained. “If you shot in black and white it looked better… It brought the artist to the forefront and separated the foreground from the background, and there are no muddled colors.”

A final reason was personal economics. “I could print my own black and white photos, whereas I would have to send the negative to a developer if I wanted color.”

In 1972, the owner of Tower Records in San Francisco asked Hulst if he would sell his photos on the sidewalk in front of his store. It was a steady way to make sales while boosting his career. “I did that for 18 years,” Hulst said, adding he met a lot of fans and rock insiders along the way who would stop to talk about shows.

The concert photography world gradually began to change in 1973 when David Bowie became the first artist to prohibit fans from bringing cameras to concerts. The practice become more widespread around 1979, when security guards started confiscating cameras at the gates.

That didn’t deter Hulst. “To keep the story of rock from being told by more than just a few photographers in New York or Los Angeles, some of us were sneaking in cameras,” he said, adding that he only got caught twice.

“There were no metal detectors back then and it got to be a cat and mouse game,” he said. “I got thrown out of a Van Halen concert twice in one night. I was taking photos from the fifth row. You could smoke all the pot you wanted, but you could not bring in a camera.”

In 1983, Hulst took a job as a photographer with the U.S. Air Force Academy but continued to shoot concerts in the evening. “I would photograph a general in the day, and a rock star at night,” he said.

Today, Hulst’s photos can be found in many places. The Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in Cleveland has purchased four of his photos and has included them in displays. His work has also been included in many album art designs, including releases by Jimi Hendrix and Bruce Springsteen.

Louis A. Zona, executive director of the Butler, described Hulst’s exhibition as “a wonderful reminder of the extraordinary contribution made to our culture by rock, blues and soul music. It also reveals much about the colorful nature of the performers who created this musical magic.”

Those who check out the “Front Row Center” exhibition at the Butler can take home samples, as prints of Hulst’s photos will be sold at the gift shop.

Hulst said he might even visit the museum for a closing reception in June, if COVID-19 regulations permit.

The Butler, 524 Wick Ave., is open Tuesday through Saturday from 11 a.m. to 4 p.m.; and Sunday from noon to 4 p.m. Admission is free.

Pictured above: This photo by Larry Hulst shows Tom Petty and Bob Dylan performing together at The Greek Theater in Los Angeles in 1986.

Copyright 2024 The Business Journal, Youngstown, Ohio.