ShaleNET Supplies Skills for Industry Pipeline

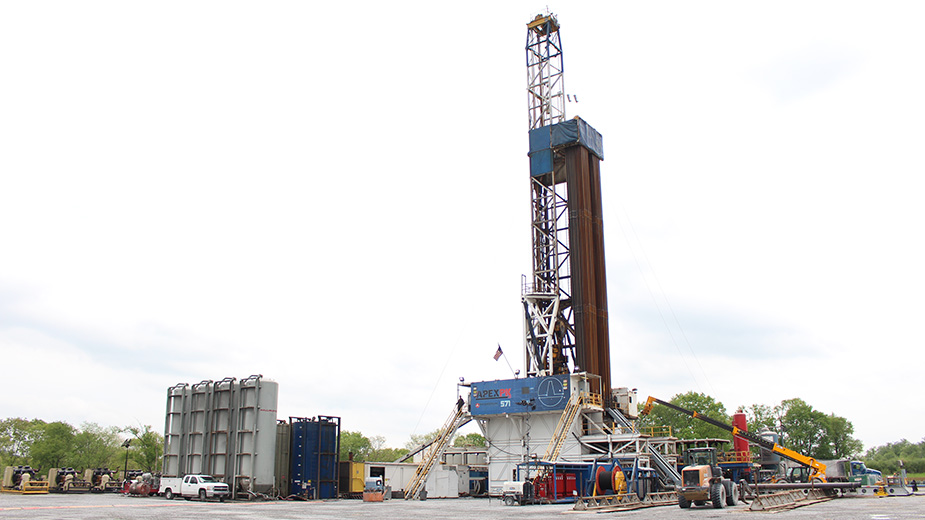

NORTH CANTON, Ohio – Conventional wisdom holds that the downturn in the oil and gas industry several years ago snuffed out much of the opportunity across the Utica shale in Ohio, or at least stunted its economic impact.

While the slump hit tube manufacturers hard, and drilling programs were curtailed, demand for workers in other segments of the industry never tapered off as pipeline projects moved forward and the growth of a vibrant end-user market started to settle in.

“Recruitment was not what you would have expected,” observes Daniel Schweitzer, director of oil and gas and environmental at Stark State College in North Canton. “We experienced high demand throughout the downturn.”

Stark State participates in Shale-NET, an initiative launched in 2010 that was leveraged from a $4.9 million U.S. Department of Labor grant. The first was awarded to Westmoreland County Community College in Youngwood, Pa.

The grant covered the cost of instruction for new training programs in response to the quickly developing oil and gas plays in the Marcellus shale in Pennsylvania and West Virginia. A $14.9 million follow-on grant issued by the U.S. Department of Labor in 2012 enabled the program to establish a new credential model and expand its capacity to other institutions, including Stark State, as exploration in Ohio’s Utica shale intensified.

The money helped to establish a training curriculum where students learn foundational skills such as applied mathematics and computer literacy, acquire entry-level and industry certification programs, and earn an associate’s degree in petroleum technology – even pursue a baccalaureate in technology management.

Those grants have since expired but ShaleNET is still going strong, thanks to private-sector partners.

Leading the charge is Chevron. In January, its Chevron Appalachia subsidiary announced it would give $630,000 to support ShaleNET programs at Stark State, Westmoreland, the Pennsylvania College of Technology and Pierpont Community & Technical College in West Virginia.

“Our success is linked to the region’s progress,” Trip Oliver, manager for policy, government and public affairs for Chevron Appalachia.

Since 2014, Chevron has awarded more than $2.1 million in grants to the program. In January, Stark State received a grant for $118,269, $90,000 designated for scholarships, the remainder for new equipment for Stark State’s ShaleNET training lab in downtown Canton.

Much of the demand comes from midstream distribution and end-user development, Schweitzer says. Across the Utica, midstream pipelines and compressor stations remain under construction, their purpose to transport the large volumes of dry and wet gas from the shale play to systems owned by energy companies such as Dominion and Marathon.

“Demand was so high, students were getting hired right out of class,” Schweitzer says. “Dominion asked us if we had a problem hiring students before they were finished with the program.”

Marathon pursues a different track where they hire through an internship program, while midstream companies such as Williams have hired one or two people a year from the program, Schweitzer says. “Companies partner with us in different ways,” he says.

To date, Stark State has graduated 62 from the program. While most graduates find employment in the energy sector, the skills they acquire such as welding and industrial maintenance are portable to Ohio’s manufacturing sector. “We haven’t had a problem placing students,” he says.

Still, it’s not easy to recruit students, Schweitzer says. “We’re still dealing with some of the negative connotations in manufacturing and applied industrial careers,” he says. “So, we have to do a lot of outreach.”

The objective of ShaleNET is not to teach students concepts such as hydraulic fracturing or drilling techniques, Schweitzer says. Instead, the program is more focused on developing a labor force around the residuals of the oil and gas play – such as midstream infrastructure or downstream projects like the Lordstown Energy Center, a natural gas-powered electrical plant under construction.

“Companies like Dominion have hiring needs and the union halls are picked clean,” Schweitzer says.

Rocky DiGennaro, president of the Western Reserve Building & Construction Trades Council, says his locals are fielding calls from outside the Mahoning Valley to help with ongoing Utica infrastructure projects.

“We’ve been getting calls from Marietta and West Virginia from outfits looking for manpower on the Nexus pipeline,” DiGennaro says. More recently, tradesmen completed a natural gas source pipeline that runs from Austintown to the new Lordstown Energy Center.

The real work is in upgrades to natural gas distribution lines across the Mahoning Valley and Ohio, DiGennaro says. “We have about 30 guys just working on pipeline distribution around here,” he says, and DiGennaro understands Dominion has set aside a hefty capital budget to upgrade its lines over 25 years. That means more work for pipefitters and laborers.

In the Columbus area, DiGennaro says, 25 crews are performing upgrades to that area’s pipeline network.

This is precisely the type of future ventures for which Schweitzer wants to groom ShaleNET graduates. “We’re training the next gas and utility workforce,” he says.

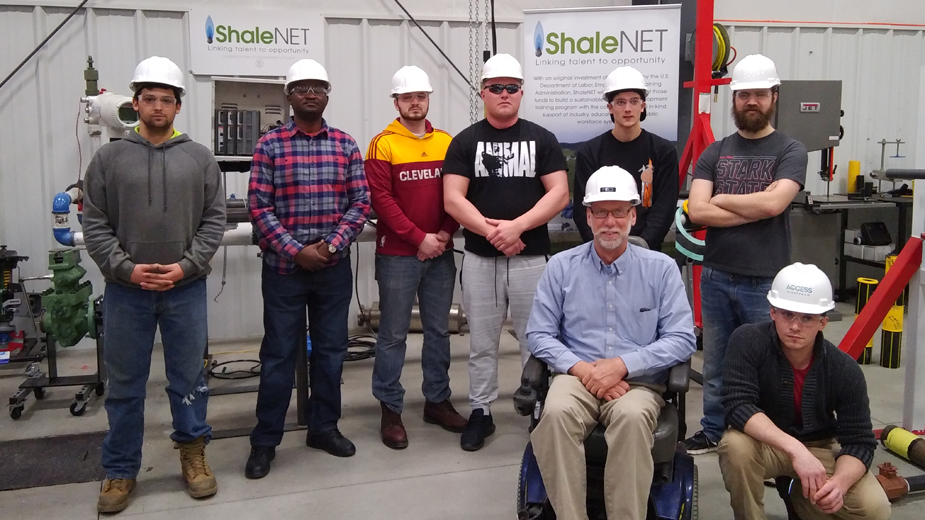

Pictured: Seated are Stark State College instructor Fred Albrecht and student John Peterson. Standing: Mitchell Stutler, Stanley Ekobi, Quinn Hill, Austin Thompson, Kyle Cattarin and Brandon Floyd.

Copyright 2024 The Business Journal, Youngstown, Ohio.