Sleepy Village of Lowellville Boasts a Raucous Past

LOWELLVILLE, Ohio – The village of Lowellville is the kind of town that smacks of idyllic charm. Antique lighting and renovated historic buildings line its main business district. A quaint gazebo anchors a small park with neatly bricked walking paths in the center of the village.

It’s mostly a quiet town – a community bisected by the Mahoning River with a little more than 1,000 residents who genuinely know one another. Few industries are left, but restaurants, small businesses and well-groomed neighborhoods dominate the village’s character today.

Yet Lowellville wasn’t always known for this bucolic image. Indeed, during the latter decade of the 19th century and well into the Prohibition era, the village earned a reputation as one of the rowdiest towns in Ohio, according to a former resident and local author who looks back with fondness on her hometown.

“Lowellville was one crazy place during the early 20th century,” says Roslyn Torella, who graduated from Lowellville High School in 1984 and today lives in Maryland. “Most of it was fueled by liquor.”

Torella is the author of Lowellville, Ohio: Murder, Mayhem and More, published in 2014. The book consists of a collection of newspaper accounts and photographs of the village spanning the 1850s to the present.

As a teen growing up in Lowellville, Torella knew little of the history of the community. As she investigated more, Torella became fascinated with the cultural, economic and social forces that shaped this small northeastern Ohio town.

“My favorite period to write about is around 1911, when Struthers and New Castle, Pa., voted to go dry,” she says. Lowellville, a community then of about 2,500 people, was sandwiched between the two cities and in a prime position to capture the “wet” market, which it did.

“Lowellville turned into one of the rowdiest towns in Ohio,” Torella says. In 1913, the village once again voted to uphold its “wet” status and business among the local bars flourished on the weekends, attracting patrons from across the region.

According to an article dated Dec. 18, 1913, in the New Castle News, which is referenced in Torella’s book, a reporter chronicled the moment the election results were tallied. “Persons who worked indefatigably for the moist cause stood last night in groups with one foot on the brass rail, and between gulps discussed glories of victory.”

The bar business was hopping and Lowellville fast became the destination spot for residents of nearby communities that had recently voted to ban the sale of beer, wine and liquor, Torella says.

“There was a streetcar line that ran from New Castle, and they would be packed on Fridays and Saturdays,” she says. “The streets were just jammed.”

And, there was enough business to go around. According to a Youngstown Vindicator account dated Aug. 3, 1915, even pickpockets saw plenty of action as they hit Lowellville during the weekends:

“Pickpockets were busy in Lowellville Saturday night and are reported to have reaped quite a harvest. The light fingered gentry found easy picking among the crowds that frequent the saloons of the village especially on Saturday nights, when lovers of the cup come in large numbers from New Castle and other dry territory in western Pennsylvania.”

One victim, Richard McCann, reported he lost $9.

Moreover, the Prohibition era apparently had little effect on quelling liquor sales or consumption in the village, Torella writes. On March 25, 1929, The Plain Dealer reported that a raid on an illegal distillery in Lowellville netted 80 barrels of liquor and a 100-gallon still.

And, on March 21, 1925, the Youngstown Telegram ran this item: “Charged with having used a teapot as a still, C.I. Brantz, former police chief at Lowellville was fined $100.”

Lowellville’s reputation as a rough and rowdy town during the early 20th century came along with its importance as an industrial center as well.

Among the first settlers in the region was John McGill, who for several months served in the American War for Independence and staked out a claim in the Western Reserve, purchasing 200 acres on the southern banks of the Mahoning.

According to industrialist Joseph G. Butler’s History of Youngstown and the Mahoning Valley, McGill established a gristmill and was followed years later by his brother, Robert, who founded a sawmill nearby. For much of the century, this section of town was known as McGillsville. Across the river, a separate community, named Lowell, emerged.

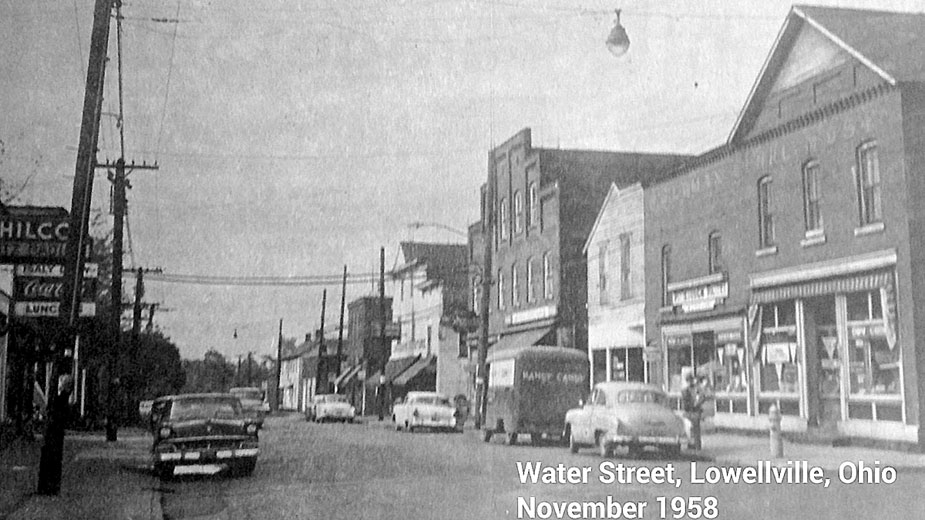

By the 1830s, the area became well known as a center of flour production and coal, which was recently discovered in a nearby hillside named Mount Nebo, Torella says. The real economic shot in the arm arrived with the construction of the Pennsylvania-Ohio Canal, which ran parallel with what was then known as Canal Street, today Water Street.

Pictured: A view circa 1958 of Water Street in Lowellville, originally called Canal Street.

“The canal was lucrative,” Torella says. “Merchants could place goods on boats and send them to Cleveland or Philadelphia. It was becoming quite a city.”

By 1872, the canal era was dead, and that year a boat by the name of The Telegraph shipped the last load – an order of flour and coal from Lowellville – along the Ohio-Pennsylvania canal. By that time, the railroad had replaced the canal system as the dominant means of mass transportation across the country, and the Pittsburgh and Lake Erie Railroad purchased the Pennsylvania-Ohio Canal’s rights of way. Today, those tracks run along the path of the original canal, now filled in.

In 1890, the two communities of McGillsville and Lowell were incorporated as Lowellville, by now a small but thriving microcosm of the industrial age. During the late 19th century, thousands of immigrants from eastern and southern Europe arrived in the Mahoning Valley seeking work in the iron and steel industry.

Lowellville became home to a large concentration of Italian immigrants, an ethnic heritage that still thrives in the community. “My family came here in the 1890s,” Torella says. Her grandfather, father and uncle all worked in what was the industrial anchor of the entire community, the Sharon Steel Corp.

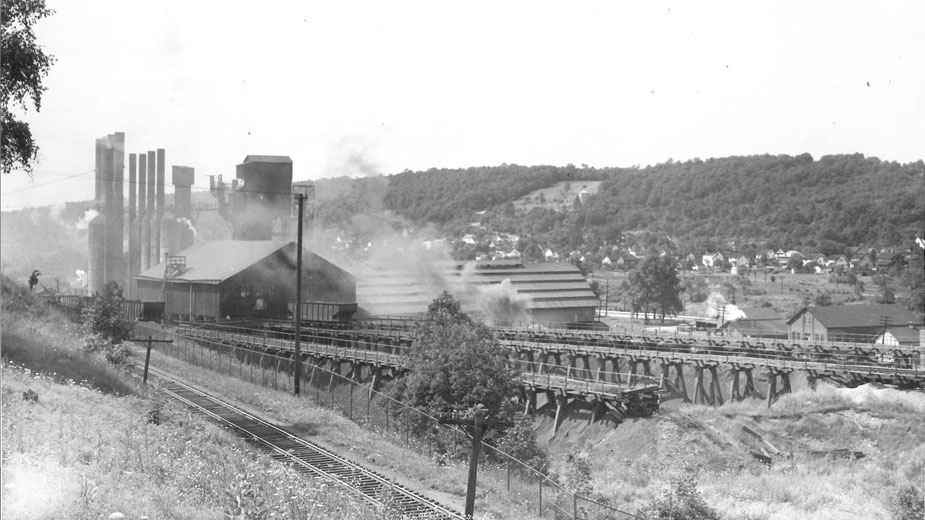

Initially known as the Ohio Iron & Steel Co., in 1845 the plant established the first blast furnace – nicknamed the “Mary Furnace” – to use raw bituminous coal in the iron-smelting process, Torella says. In 1917, the Sharon Steel Hoop Co. purchased the factory, and in 1936 it became Sharon Steel Corp. The mill was idled in 1961 and was closed in 1963.

“There were around 400 employees there,” Torella recalls. “My grandfather, father and every one of my uncles worked there. Entire families were impacted.”

Lowellville also earned a reputation as a community that didn’t shrink from duty, especially during the Second World War. An article written by former Vindicator politics editor and one-time Lowellville resident, Clingan Jackson, dated Oct. 25, 1942, illustrates how the war affected the village.

“The war has come to every American community, but Lowellville has been hit harder than any like community in the Mahoning Valley,” Jackson wrote. “Nearly 15%, it is unofficially reported, have already answered the call to colors.”

That number would increase to about 20% of the city’s population by the war’s end in 1945, Torella says, many of whom were the children of Italian immigrants that had not as yet received U.S. citizenship.

“It’s ironic. As these immigrants were registering as enemy aliens, they sent their sons out to fight,” she says.

Pictured at top: The former Sharon Steel Co. plant in Lowellville served as the village’s industrial base until 1961, when the mill was idled. It formally closed in 1963.

Copyright 2024 The Business Journal, Youngstown, Ohio.