Supreme Court Case Changed Grove City College Forever

By Nick Hildebrand

Senior Editor Marketing & Communications, Grove City College

GROVE CITY, Pa. – Forty years ago this week, a U.S. Supreme Court decision heralded a defining moment in Grove City College history.

On Feb. 28, 1984, the high court issued its ruling on Grove City College v. Bell, putting an end to the nearly decade-long legal battle over federal funding and the College’s right to self-determination. It marked the beginning of a new era, one in which Grove City College was recognized as much for the courage of its convictions as its reputation as one of America’s best Christian liberal arts colleges.

The court’s finding that financial aid awarded to eligible students constituted federal financial assistance to the college was a loss that put Grove City College at a crossroads. Accepting federal funding would subject the college to government control and political influence that could run counter to its longstanding commitment to faith and freedom.

“It blurred the line between public and private education when it comes to government control. If students used grants to attend GCC, the college would cease to be truly independent. We would be giving the Department of Education a regulatory blank check, so to speak,” GCC President Paul J. McNulty said.

The college’s decision to exit the federal student aid programs rather than surrender its autonomy made GCC the standard bearer for academic freedom and independent higher education.

“The Court Case,” as it has become known, began in 1977, when then GCC President Charles S. MacKenzie refused to sign a form that indicated the college would comply with Title IX, the federal law prohibiting discrimination against women in education.

While the college, which as a matter of Christian conscience has never discriminated against women or anyone else, didn’t object to the law, its leaders maintained the form was an attempt by the government to take control of private education. They firmly believed that signing off on it would subject the school to unwanted and unwarranted federal regulation.

Since, as a matter of principle, the college has never accepted any federal assistance, the government’s position that institutions that refused to sign off on Title IX compliance would lose their federal funding wasn’t initially alarming. In late 1977, the government identified federal grants and student loans as aid to the college and threatened to withdraw that support from GCC students.

On Nov. 8, 1978, the college and four students sued the Department of Education (T.K. Bell was the secretary when the case went to court) to save students’ financial lifelines.

“We feel somewhat like David facing Goliath on this issue. Yet because we believe we are right in seeking to maintain our integrity as an independent college, we will continue to reject both government funding and this type of government intervention,” MacKenzie said at the time.

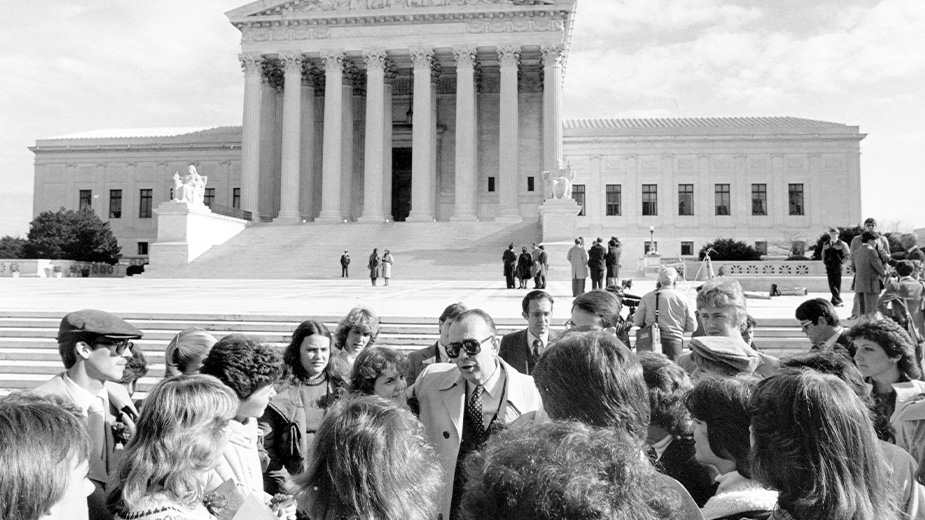

The case wound its way through lower federal courts – with one judge wondering why the government was “hounding” a school that supported women’s rights – until it reached the Supreme Court in fall 1983.

The college argued that Title IX, which governs education programs receiving federal financial assistance, didn’t apply to GCC because of its longstanding refusal to take federal money. It maintained that loans and grants were aid to students, not the college, and that taking them away from students because of the college’s actions was unfair. Despite sympathetic words from several justices – and support from a wide spectrum of the public and the media – the college lost the case.

Rather than comply with regulations that could threaten its core commitment to faith and freedom, GCC withdrew from federal education grant programs immediately, replacing the money that helped needy students cover their tuition with its own financial aid system.

The loss in court, however, wasn’t seen as a victory for those who advocated government control of education. The Civil Rights Restoration Act – known as “the Grove City bill” – was passed by Congress to expand Title IX to every aspect of college life. The bill was vetoed by President Ronald Reagan.

“The truth is, this legislation isn’t a civil rights bill,” Reagan said. “The Grove City bill would force court-ordered social engineers into every corner of American society. I won’t cave to the demagoguery of those who cloak a big government power grab in the mantle of civil rights.”

Congress managed to override Reagan’s veto, but that law had little impact on GCC, which severed its last connection to the federal government in 1996 when it withdrew completely from federal student loans programs.

Turning off the federal money spigot required “enormous determination and sacrifice,” McNulty said, noting, “Our deeply held convictions come at a price.” Over 40 years, the college has passed up millions in federal support that other schools rely on to remain open, but that has helped the college in the long run.

“Losing the Supreme Court case was one of the best things that has happened to Grove City,” McNulty said. “It seems counterintuitive to assert that declining federal funding has strengthened the college’s financial sustainability and affordability, but this is truly the case. Our alumni and friends have stepped up magnificently to support the college’s independence and allow us to build a financial aid program that far exceeds what the federal government currently offers and raise millions to replace federal grants for research and facilities.”

Pictured at top: In this 1983 photo, then Grove City College President Charles S. MacKenzie talks to students and reporters outside the U.S. Supreme Court before the college argued its case before the justices.

Published by The Business Journal, Youngstown, Ohio.