think[box]: Thinking Inside the Box

Case Western’s Maker Space Takes Ideas From Conception to Launch

By Dan O’Brien

Imagine a portable device that provides critical medical information within minutes by reading a drop of blood. Or, a high-end fashion garment that changes colors but whose technology could enhance safety protocols in the construction industry. Then, consider an adhesive strip that one day might transform the aeronautics, wind turbine and transportation industries.

It’s just a sample of what has emerged from those who think inside the box – in this case, a seven-story idea factory in the intellectual heart of Cleveland.

“From the very beginning, we envisioned this as more than a maker space,” says Malcolm Cooke, executive director of the Larry Sears and Sally Zlotnick Sears think[box] on the campus of Case Western Reserve University. “We see us as an ecosystem around innovation and entrepreneurship. It’s really a catalyst for a change in culture within the university and around our community.”

The Sears think[box] was established four years ago with the intent of creating an advanced, hands-on innovation and entrepreneurship laboratory accessible to students, companies and the general public. The operation is funded entirely through philanthropy; gifts have ranged from $50 to several million dollars.

But it’s think[box]’s egalitarian business model, Cooke says, which has encouraged a level of interaction and collaboration that entrepreneurs and thinkers relish so they can take their ideas to the next level.

![Think[box] hosts 6,000 visitors a month, says Malcolm Cooke, executive director.](https://businessjournaldaily.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/cooke.jpg)

Think[box] hosts 6,000 visitors a month, says Malcolm Cooke, executive director.

“What drives us is that we are open-access,” Cooke says. “A student might be working on something that is a challenge, but next to them might be someone with the skill set they need to look at these challenges and problems. Those serendipitous interactions become exceedingly valuable.”

Absent this model, those collaborations would be very limited, notes Cooke, also an associate professor of mechanical and aerospace engineering at Case Western. Since the initiative was launched, the operation has grown from a 6,000-square-foot space to a 50,000-square-foot building seven stories high that houses just about every type of operation vital to the development, marketing and launch of a new product from the ground up.

Indeed, think[box]’s new building is designed precisely along these lines, each floor dedicated to a specific function that serves product development, research and marketing. As such, it’s possible that a burgeoning entrepreneur could take an idea and march it up think[box]’s seven flights of stairs through iteration, prototyping, fabrication, business planning and product launch.

The first floor is an unfinished community room while the second floor is devoted to collaborative discussions – a wide-open space furnished with round tables absent any encumbrances in an effort to encourage the free-flowing exchange of ideas.

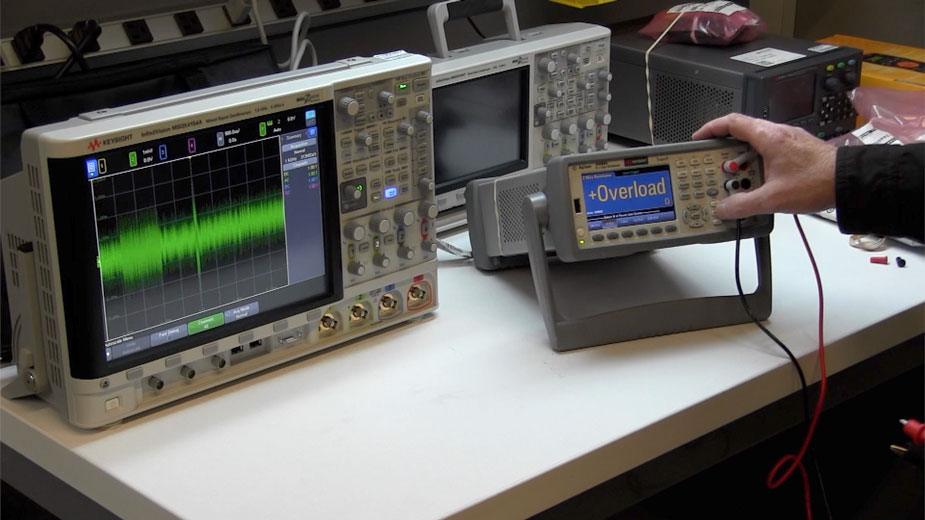

It’s the third and fourth floors, however, that draw the most activity, observes Ian Charnas, manager of think[box]. The third floor is dedicated entirely to prototyping through the use of some of the most sophisticated equipment on the market today. “On this floor, we have our higher-end machines,” he says, such as 3-D printers, laser cutters, vinyl cutters, computers, and soldering and testing equipment used in electronics.

The third floor contains a series of larger, high-resolution 3-D printers and a select number of desktop printers for components that are first digitally rendered and then formed through additive manufacturing, Charnas says. And, in the electronics section of the third floor, patrons can use a 3-D microscope to peer into the miniature world of circuit manufacturing.

“You’re looking at the silicon that makes up a microchip,” he says, demonstrating the magnification power and 3-D capabilities of the microscope.

Such equipment would be an asset for any university, Charnas says. However, he emphasizes, the use of these machines is free and open to the public, a concept that has amazed some of the tech world’s most influential and creative minds.

About three years ago, Steve Wozniak, the co-founder of Apple, took time to visit think[box], Charnas relates. While he was impressed with the precision and scale of the organization’s equipment, he was floored by the prospect of opening these machines for public use.

“He was blown away at that idea,” Charnas recalls.

Think[box]’s fourth floor is reserved for fabrication processes. Welding stations, lathes, CNC machines – traditional manufacturing equipment that might be necessary to complete a component or project – are located here. The fifth floor is designated for student projects that range from engineered dune buggies to rockets, and robots.

![Benjamin Lindstrom says all the work on his team’s robots is done at think[box].](https://businessjournaldaily.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/lindstrom.jpg)

Benjamin Lindstrom says all the work on his team’s robots is done at think[box].

“Think[box] houses our entire team,” says Benjamin Lindstrom, a junior at Case Western and member of its robotics team. The squad has nine months each year to build a robot that will be entered into NASA’s Robotics Mining Competition in May.

“We did most of our manufacturing and fabrication work on the fourth floor,” Lindstrom says. When finished, the Case robot will navigate through an obstacle course and dig through dirt resembling Martian soil before driving back to an area where it deposits the dirt.

“Last year, we achieved fifth place overall, first place for our systems engineering paper, and second for our presentation,” Lindstrom says.

Charnas says accessibility to these tools and think[box]’s mentorship culture has helped to launch more than 100 companies first conceived at Case Western.

Apollo Medical Devices, for example, used the resources at think[box] to develop and launch its product – a hand-held mobile device that uses a less painful method to extract blood from a patient and measure levels such as pH, potassium and creatinine – which could prove vital to first responders or military personnel. Those tested get results in about five minutes.

“There are a lot of different projects,” Charnas says. “You’ll see social entrepreneurship, art, basic science. It’s not just engineers.” Indeed, engineers make up 49% of the visits, so more than half of those using think[box] are from other disciplines.

A collaboration between the Cleveland Institute of Art and Case Western, for example, yielded a fashion garment that gradually changed color as the model moved. “An incubator approached them to see if they could use this technology and make vests for the construction industry,” he says.

Think[box] averages 6,000 visits a month, making it the third-most used building on campus, after the gymnasium and the library, Charnas says. Often, people use think[box] to make single gift items for friends or family.

Those who commit themselves to the entire process may reap the benefits of having devised industry-changing technology.

Prince Ghosh, a third-year undergraduate in Case Western’s mechanical and aerospace engineering program, conceived his idea in his first-year physics class. It was during this course that he became intrigued over ways to reduce drag and resistance on aircraft, wind turbines and tractor-trailers.

“What me and my co-founders have created is a solid-state electrode in the form of an adhesive strip,” he says. The strips could be affixed to an aircraft wing, a wind turbine or a semi truck and replace the bulkier fixtures that today house the same components. “When hooked up, this transforms the way air flows around the blade, wing, or truck,” he says.

Thus, this new application stands to reduce drag and lower overall energy use, Ghosh says. “All of the 3-D printing, circuit facilities – all of the prototyping and testing – was done at think[box],” he says.

Ghosh first came across decades-old research on the subject performed by Soviet-era Russian and NASA scientists, he says, but the studies never emerged from the laboratory. “They never had hard evidence or a product that entered the marketplace,” he says. “I saw this as an opportunity to put forth a value proposition that would make a difference not just in one industry, but across multiple industries.”

Today, Ghosh’s company, Boundary Laboratories LLC, is searching for strategic industry partnerships in aerospace, energy and transportation. “We’re looking to form partnerships with a renewable energy company in Chicago. And we’re working with NASA Glenn to validate the idea,” he says. “By the end of the summer, our goal is to have a functional prototype on a semi-truck trailer.”

Still, not all ideas work. Staying on course to see a product come to fruition isn’t for everyone, says Bob Sopko director of LaunchNet, which provides business, marketing and financing help to turn these ideas into real scalable products and services.

“Think[box] makes, I sell,” he says, then laughs. LaunchNet has space in the building and is slated to occupy more office space once renovations on the sixth floor are finished. The seventh floor, which will house a full-service incubator, is also under development.

Sopko says students who might have a good idea often retreat from taking it further once they are informed of the hard work and long hours it will take to launch their business. “First, we see if there is a next level,” he says. “I tell them to have fun with it, enjoy it, and I’ll work with you if you have something.”

Outlets that have proven successful are industry competitions where these ideas are proven directly before those most likely to use them, Sopko says. “Competitions are a good way to expose your idea, to get feedback, and possibly some funding,” he says.

Apollo Medical, for example, has raised about $1.2 million — $225,000 of which was from the National Science Foundation, Sopko says. Another venture, Everykey.com, a small fob capable of unlocking everything – your computer, phone, house and your car – has raised $2 million.

“It was a student project, and now they have 11 employees,” Sopko says. Today their offices are in the Little Italy section of Cleveland. “We encourage these students. You may have an idea,” he says, “but founders need help.”

Pictured above:Ian Charnas, manager of think[box], stands in the prototyping room on the third floor. It houses 3-D printers and laser cutters.

Copyright 2024 The Business Journal, Youngstown, Ohio.

![ian charnas, think[box], prototyping, 3D printers](https://businessjournaldaily.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/ian-charnas.jpg)