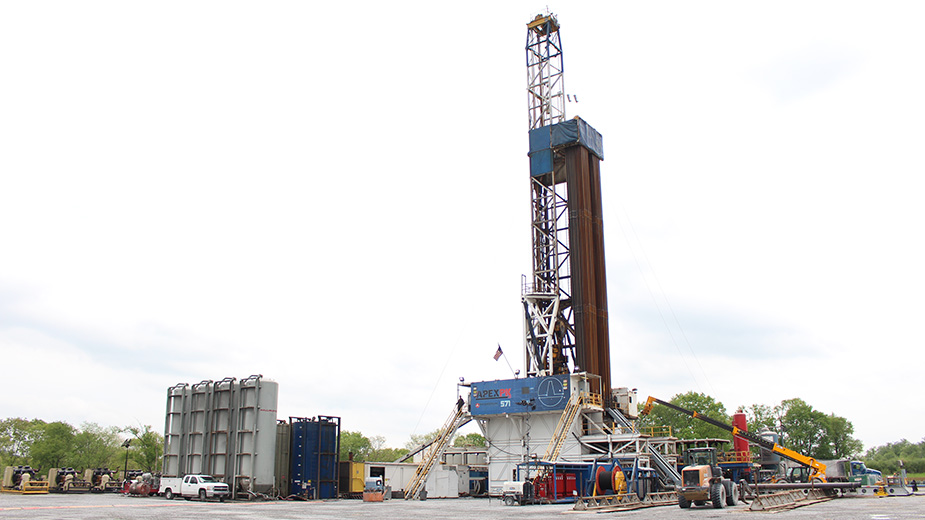

US EPA Sued over Disposal of Fracking Waste

WASHINGTON – A coalition of community and environmental organizations sued the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency Wednesday, calling for regulations to stop oil and gas companies from handling and disposing of drilling and hydraulic fracturing – or fracking — waste in ways they say threaten public health and the environment.

The suit was filed in U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia.

The organizations are pushing the EPA to issue rules that address practices such as the disposal of fracking wastewater in underground injection wells. Such wells, they say, have accepted hundreds of millions of gallons of oil and gas wastewater and are linked to earthquakes in Arkansas, Colorado, Kansas, New Mexico, Ohio, Oklahoma, and Texas.

“Updated rules for oil and gas wastes are almost 30 years overdue, and we need them now more than ever,” said Adam Kron, senior attorney at the Environmental Integrity Project, in a prepared statement. “Each well now generates millions of gallons of wastewater and hundreds of tons of solid wastes, and yet EPA’s inaction has kept the most basic, inadequate rules in place. The public deserves better than this.”

The coalition consists of the Environmental Integrity Project, Natural Resources Defense Council, Earthworks, Responsible Drilling Alliance, San Juan Citizens Alliance, West Virginia Surface Owners’ Rights Organization, and the Center for Health, Environment and Justice.

The lawsuit calls on the court to set strict deadlines for the EPA to comply with its obligations to update waste disposal rules.

“Waste from the oil and gas industry is very often toxic and should be treated that way,” said Amy Mall, senior policy analyst at the Natural Resources Defense Council, in a prepared statement. “Right now, companies can get rid of their toxic mess in any number of dangerous ways — from spraying it on icy roads, to sending it to landfills with our everyday household trash, to injecting it underground where it can endanger drinking water and trigger earthquakes.

“EPA must step in and protect our communities and drinking water from the carcinogens, radioactive material and other dangerous substances that go hand-in-hand with oil and gas waste,” she said.

The organizations would have the EPA ban the practice of spreading fracking wastewater on roads in winter and fields and require landfills and ponds that receive drilling and fracking waste to be built with liners. They say the liners should be sufficient to protect the structural integrity of the ponds and prevent spills and leaks from getting into groundwater and streams.

The lawsuit contends that the acceleration of oil and gas exploration for shale gas over the last 10 years has led to “an enormous amount of solid and liquid waste resulting from drilling and hydraulic fracturing.” This waste, the groups assert, poses a direct threat to the environment and public safety, that the EPA has done little to regulate its disposal.

“In 1988, EPA promised to require oil and gas companies to handle this waste more carefully,” said Aaron Mintzes, policy advocate for Earthworks, in his statement. “Yet neither EPA nor the states have acted. Today’s suit just says 28 years is too long for communities to wait for protections from this industry’s hazardous waste.”

The lawsuit cites several examples the groups say are problems caused by the improper disposal and handling of fracking and drilling waste. Among them is an underground injection well in Youngstown, Ohio, that the complaint says triggered 77 earthquakes, the largest a 4.0 magnitude quake that hit the Mahoning Valley on New Year’s Eve 2011.

Other seismic tremors were detected in Alabama, Oklahoma, Arkansas, Colorado, Kansas, New Mexico, Oklahoma and Texas, the groups say. Additional environmental problems and contamination associated with drilling and oil and gas transportation have occurred in Pennsylvania, West Virginia, North Dakota, and Colorado, the groups posit.

“A major reason for the industry’s use of injection wells to dispose of toxic fracking waste is the low disposal cost,” said Teresa Mills, director of the Ohio field office for the Center for Health, Environment and Justice. “We reject this reasoning because the public’s health and safety must come first.”

Copyright 2024 The Business Journal, Youngstown, Ohio.