Flashback: Turbulent, Deadly Vietnam War on Display

By Pat Springer

PITTSBURGH — By most accounts, it was an unwinnable war. Its divisiveness tore apart our country. It caused pain, grief, and anger. No ticker tape parades greeted returning veterans. No jubilant Times Square photos celebrating victory splashed across the front pages.

If World War II defined the greatest generation, then the Vietnam War laid bare the patriotism, mistrust, duty, and loyalties of the baby boomers. All this emotion and history are captured in a highly personal and groundbreaking exhibit, The Vietnam War: 1945-1975, at the Senator John Heinz History Center in Pittsburgh.

The exhibit, which opened April 13 and runs through Sept. 22, showcases one of the most controversial conflicts of the 20th century. Indeed, disclaimers about graphic and disturbing content unsuitable for children are posted. Developed in partnership with the New-York Historical Society, the exhibit spans the duration of U.S. involvement in Indochina, presenting stories, photography and artifacts that tell the deeply personal stories of the men and women, including Pittsburghers, who were impacted by the war.

Those who were there the day I attended included a veteran who stood with his wife in front of Tet Offensive video footage, pointing out where he was during the fighting. Groups of veterans sat in silence. Some visitors came in wheelchairs. Some came with younger family members, sharing a few memories many would prefer to forget.

It begins in 1945, when President Truman, reacting to the threat of a Cold War pitting American capitalism against communism, contributes arms and money to France’s effort to recolonize French Indochina (Laos, Cambodia, and Vietnam).

Using wall murals, video footage, personal interviews, and extensive maps, the exhibit leads the visitor through the next 30 years, from the partition of Vietnam in 1954 that divided it into north and south to the signing of the Paris Peace Accord in 1973 and finally, to the fall of Saigon in 1975.

The major players are all there. Communist leader Ho Chi Minh. South Vietnam President Ngo Dinh Diem. U.S. Presidents Truman, Eisenhower, Kennedy, Johnson, and Nixon. Gen. William Westmoreland. Gen. Vo Nguyen Giap, leader of North Vietnamese Army. Defense Secretary Robert McNamara. But it’s the story of the 58,351 Americans who died and the thousands more who fought alongside them.

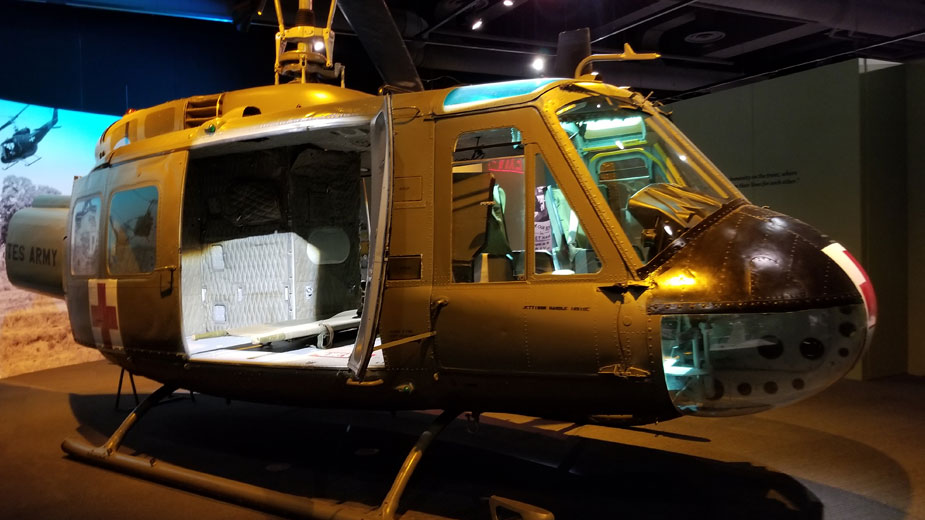

Permeating the exhibit is the constant chilling sound of the whirring blades of a UH-1H “Huey” helicopter deployed by the U.S. Army from 1967 through 1970. The Huey is, in fact, the centerpiece of the exhibit.

A Vietnamese bicycle shows the rudimentary way the North Vietnamese Army, in its guerilla insurgency against the south, delivered supplies and goods via human transport along the Ho Chi Minh Trail.

What began as a civil war between North and South Vietnam in the 1950’s became a rallying call by the U.S. to prevent the spread of communism throughout Southeast Asia. As early as 1964, however, the policy was failing. Senior U.S. government officials, believing that if one country, Vietnam, fell to communism, its neighbors, Laos, Cambodia, Thailand and Burma, would swiftly follow. This domino metaphor became the justification for all escalating U.S. involvement.

Neither Eisenhower, Kennedy, Johnson — nor ultimately Nixon — wanted to be criticized as soft on Communism so each succeeding president continued to up the ante sending more weapons, advisers and soldiers. Kennedy sent the Green Berets. Johnson sent the Marines.

Johnson’s decision to keep fighting is well documented. McGeorge Bundy, Johnson’s military adviser who was in Vietnam in 1964, wrote the president after the Gulf of Tonkin confrontation: “The situation is deteriorating and without new U.S. action defeat appears inevitable.. . there is still time to turn it around but not much.”

Johnson, worried about American credibility, turned up the pressure on Hanoi and the Viet Cong. On March 2, 1965, more than 100 U.S. planes bombed North Vietnamese targets. Six days later, the Marines landed at Danang. They were now fighting a ground war to defend the credibility of the administration and avoid a humiliating defeat. It was estimated that the Viet Cong controlled 50% of the South’s countryside during the day and 75% at night.

By the summer of 1965, opposition to the war was growing and the exhibit showcases full-sized wall murals featuring the growing protest activity. Draft-card burnings amid chants of “love, not war” and “peace now’ echoed on college campuses across the country. Students for a Democratic Society, various religious groups, and prominent public figures marched in the streets. On July 28, 1965, Johnson spoke to the nation and announced an escalation in the military draft and the fighting forces — from 75,000 to 125,000 immediately. The monthly draft call, then 17,000, doubled to 35,000.

The numbers became staggering. From 1966 to 1967, U.S. troops totalled 485,600 and 45% of the U.S. public believed sending troops to Vietnam was a mistake.

In January 1968, the Tet Offensive by the Viet Cong became the turning point, confirming that the war could not be won. More than a half million U.S. soldiers were in country and public sentiment against the war further escalated.

A hospital setting in the exhibit recreates the horrors of the Offensive, when more than 3,000 U.S., 50,000 Viet Cong soldiers, and 14,000 Vietnamese civilians were killed, leaving more than 600,000 homeless. The scale and fierceness of more than 100 attacks on cities surprised the U.S. and South Vietnamese forces. Much of the fighting surrounded the historic city of Hue and at the Marine base of Khe Sanh. The living room war, anchored by Walter Cronkite, became real and the display at the exhibit, with a television console, is unsettling reminder of what we watched every night.

Nixon continued the fighting, again to avoid humiliation, until 1969 when, in an effort to quiet public discontent, he began to gradually withdraw troops. Even so, opposition to the war continued to mount.

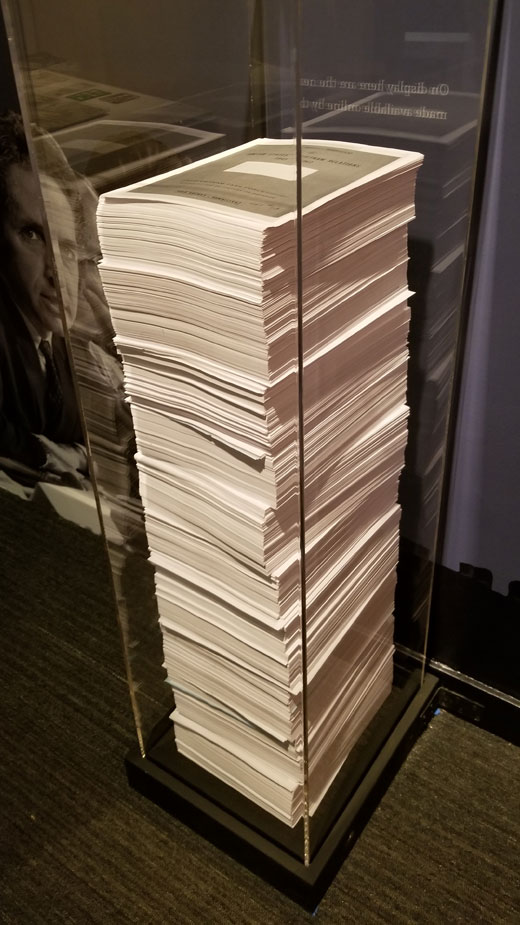

In June 1971, The New York Times published The Pentagon Papers, the 7,000-page classified document leaked by Daniel Ellsberg that detailed how the nation’s presidents had misled the country about the war. In a corner of the exhibit, stacked inside a four-foot-high plexiglas enclosure, are The Pentagon Papers that led to a landmark Supreme Court decision upholding the First Amendment

Challenges to Nixon’s war strategy increased and in January 1973, the Paris Peace Accord ending U.S. involvement in the war was signed

Prisoners of war, 591 of them including the late Sen. John McCain, returned home; 58,315 U.S. military personnel did not. Saigon fell on April 30, 1975. Today it is Ho Chi Minh City and a bustling tourist destination

Pictured at top: The UH-1H “Huey” helicopter is the centerpiece of the exhibit.

The Heinz History Center, 1212 Smallman St., is open daily from 10 a.m. to 5 p.m.

Copyright 2024 The Business Journal, Youngstown, Ohio.