Voices of Former Slaves Preserved in the Mahoning Valley

YOUNGSTOWN, Ohio – One summer day in 1937, an employee of the Works Progress Administration – the WPA – ascended the porch steps of a small bungalow at 1671 Jacobs Road in the Sharon Line district of Youngstown’s east side.

Frank M. Smith had a singular task: to track down and interview former slaves who had experienced the hardships of plantation life during the mid-19th century.

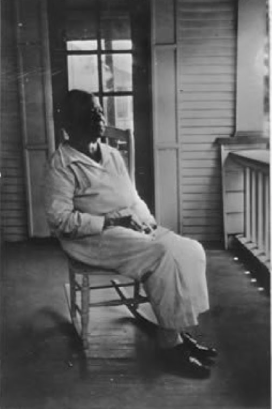

It was here he found Melissa Barden, who was born near Summersville, Georgia, on a plantation owned by David Lowe in Chattooga County. The date of her birth is unknown, and when asked how old she was, she replied, “I’s way up yonder somewhere between 80 or 90 years.”

During the 1930s, writers, sociologists, folklorists and historians fanned out mostly across the South and Midwest in an effort to preserve the heritage and recollections of former slaves. More than 2,300, were interviewed for the WPA – sponsored Federal Writers’ Project. Most still lived in the South, but more than 30 were located in Ohio. Three of them lived in the Mahoning Valley.

The interviews were compiled into 17 volumes of transcribed accounts titled “Slave Narratives: A Folk History of Slavery in the United States From Interviews With Former Slaves.” Interviewers were not trained in the phonetic transcription of speech, but were urged that language with different pronunciations than the norm “should be recorded as heard,” thus reproducing the dialect in the transcripts. All quotations are verbatim from those reports.

To find former slaves living in the industrial heartland of the North wouldn’t have been unusual during the 1930s. Many migrated North in the years following the end of the Civil War in 1865 and the era of Reconstruction, which officially ended in 1877. Moreover, between 1916 and 1918, more than 400,000 African-Americans fled the South in order to seek employment in the industrial and railroad centers of the North. By that time, the southern economy had tanked, as a boll weevil infestation ruined the cotton crop between 1915 and 1920. Simultaneously, northern industry was stimulated after 1917 as a result of the United States’ entry into World War I – and steel mills, railroads and other manufacturing concerns were famished for workers. Many of these younger workers brought extended family members with them – mothers and fathers who had lived in the South under the whip.

Yet Barden’s story reflects the complexity within the slave system of the South. Indeed, Barden said that her owner, David Lowe, treated her well on the plantation, and that she “loved him.” The one time that Barden felt any ill will toward Lowe was when he sold her mother, leaving her and her sister alone. Lowe then sold her sister, she recounted.

Pictured: Melissa Barden.

Most of the time, though, Barden looked back with fondness on life on the plantation, especially dancing and singing southern folks songs such as “Shoo Fly Go ‘Way From Me” in the evening after the day’s work was done.

Once the Civil War ended, Barden’s mother attempted to locate all four of her children, but could only find Barden. They moved to Newton County and worked on a plantation there before heading north and to Youngstown. Here, she married and had children, and at the time of her interview, lived with her daughter Nany Hardie.

When asked if she would object to a photograph, Barden conceded, “all right, but don’t you-all poke fun at me because I am just as God made me.”

The house on Jacobs Road still stands. Built in 1900, the front porch on the single-story dwelling is the worst for wear and there are signs that the roof has been repaired recently in places. Two hosta plants bracket a walkway leading to the porch steps, which are in need of maintenance.

Other former slaves who lived in the Youngstown area during the Great Depression recount a completely different – and terrifying – experience than Barden’s.

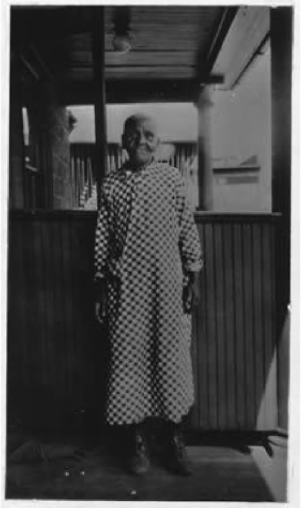

Phoebe Bost, who at the time lived at 3461 Wilson Ave. in Campbell, told Smith that she could not exactly recall her age, but she was told at the time of emancipation that she was roughly 15 years old. Bost was born on a plantation near New Orleans, and she remembers her first owner – a man by the name of Simons – taking her to a slave auction where she was sold to another owner, Val Mooney. Both owners, she recalled, were cruel, “and would administer a whipping at the slightest provocation,” Smith wrote.

On Mooney’s plantation, there was no singing or dancing – no recreation at all, Bost recalled. She was a nurse maid who cared for children, claiming “I had to hol’ the baby all de time she slept, and sometimes I got so sleepy myself that I had to prop my eyes open with pieces of whisks from a broom.”

Pictured: Phoebe Bost.

At the time of her interview, Bost was a widow and lived with her daughter at the Wilson Avenue address, which no longer exists. “Their home is fairly well furnished and clean in appearance. Phoebe is of slender stature, and is quite active in spite of the fact that she is nearing her nineties,” Smith writes.

Other former slaves across the state vividly recalled witnessing whippings, beatings, murder, intimidation, and the breaking up of families by way of the auction block.

“If I could roll up my sleeve, I could show you a mark that come from a beatin’ I had with a cow-hide whip,” Catherine Slim of Steubenville told a WPA interviewer on June 9, 1937. “Dey whip me for nothin’.”

Richard Toler of Cincinnati related to Ruth Thompson that he “never had no good times till ah was free.” Born on a plantation owned by Henry Toler in Virginia near Lynchburg, Toler said that despite the beatings and whippings that occurred regularly on the farm, he was left untouched, even though he’d attempted to escape several times.

“I jus’ tell them – if they whipped me, I’d kill ’em, and I nevah did get a whippin,’ ” Toler said to Thompson. Others didn’t survive punishment. “Whipped ‘em to death,” he said of several on the plantation who were captured. “Ah guess they killed three or fo’ on Toler’s place when ah was there,” he said. “Ah never had no good times till ah was free.”

For some, newfound freedom was as confusing and terrifying as the institution of slavery. “When the slaves heard they had been set free, I remember a lot of them were sorry and did not want to leave the plantation,” said David Hall, who was born in Goldsboro, North Carolina, in 1847 and resided in Canton in 1937.

Hall was among the more fortunate in that he didn’t live on a plantation, but rather in town inside a cabin with his mother, who worked as a cook in a hotel. His job was to work at the military school in Goldsboro, but both his and his mother’s wages were turned over to his owner. Still, Hall said he learned to read and write English with the help of his master’s daughter.

“I was about 14 when the war broke out and remember when the Yankees came through our town. There was a Yankee soldier by the name of Kuhns who took charge of a government store. He was the man who told me I was free, and then gave me a job working at the store.”

But being free didn’t ensure an ex-slave’s safety, even after Gen. Robert E. Lee’s surrender in April 1865 and the end of the war. “I do remember the night riders,” Hall said. “They put the horse shoes on the horses backwards and wrapped the horses’ feet in burlap so we couldn’t hear them coming.”

The so-called “Night Riders” the precursor of what would become the Ku Klux Klan – were southern whites determined to use intimidation tactics in order to quash freedmen’s rights and livelihoods in the South. “The colored folks were deathly afraid of these men and would all run and hide when they heard they were coming,” Hall said. “These night riders used to steal everything the colored people had – even their beds.”

Shortly after the war, that same Union soldier that managed the government store opted to move north to pursue his interests in a flourmill in Canton. In 1866, he asked Hall to join him, and gave him a position as a miller at what was in the 1930s called The Ohio Builders and Milling Co. “I worked there until the end of last year,” he told a WPA interviewer in 1937. “I was 90 years old the 25th of last month.”

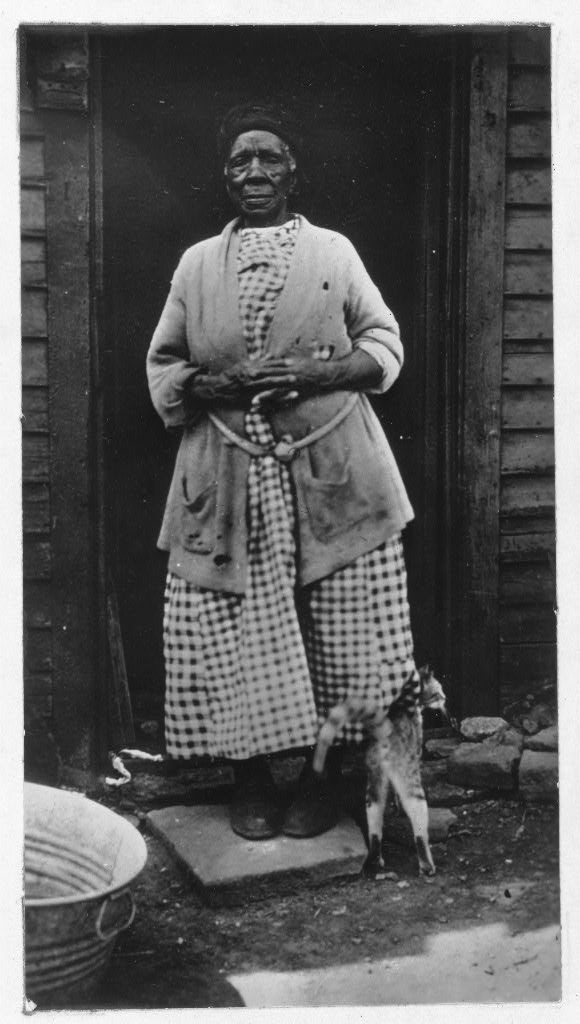

Angeline Lester, who lived at 836 W. Federal St. in a “dilapidated one-story structure” that does not exist today, told the WPA’s Smith that she now devoted all of her time to “Da Lord.”

“The Lord does not want me to smoke, or drink even tea or coffee – I must keep my strength to work for the Lord,” she said.

Lester lived alone, along with several cats and chickens that she kept in the house with her. She was born in 1847 on a plantation owned by Mr. Womble in Stewart County, Georgia, where she lived until she was about four years old.

Pictured: Angeline Lester.

Her father was sold off to a doctor in Brookville, Georgia, while Lester, her mother, and sister, were sold to a plantation owner near Benevolence, Georgia.

Any news about the war was kept from them, Lester said. However, once the fighting had ended, she recalls attending a celebration in Benevolence. It was the first time she recalls tasting a roasted piece of meat.

The following Sunday, Lester said that all of the slaves were called into the master’s quarters, where he informed them that they were now free. Those that wished to go could go, and those that wished to stay on the plantation would be paid a fair wage.

“My father came and gathered us up and took us away and we worked for different white folks for money,” Lester said. After her parents died, she married John Lester and eventually settled in Youngstown after his death.

A photograph of Lester standing in her doorway of her W. Federal Street – today, Martin Luther King Jr. Boulevard – dwelling wearing a checkered blouse and a dingy overcoat is in the archives of the Library of Congress. At her feet is a very thin cat, its tail blurred by it scampering across the entranceway, and a small washtub. After the picture was taken, Lester asked Smith what he would do with it. He replied it would be sent to Washington D.C. “Lawsy me,” she said. “If you had told me befo’ I’d fixed up a bit.”

The Slave Narrative Collection in the Library of Congress consists of texts derived from oral interviews. The interviewers were white, and were instructed to treat “words that definitely have a notably different pronunciation from the usual should be recorded as heard.” The transcriptsand what was interpreted as the “usual” pattern of speech were influenced by stereotypes prevalent in the 1930s, and the language may be offensive to readers today.

Pictured: In 1937, former slave Melissa Lowe Barden lived in this house at 1671 Jacobs Road in Youngstown. It was built in 1900.

Copyright 2024 The Business Journal, Youngstown, Ohio.