When RFK Took on the Youngstown Rackets

YOUNGSTOWN, Ohio – Sixty years ago this August, a former heavyweight boxer living in Youngstown was called to Washington, D.C., for what may have been his toughest and potentially most dangerous bout ever.

Embrel Davidson had a solid career, posting 36 wins and six losses over nine years in the ring. On Aug. 7, 1958, however, Davidson found himself facing not a singular opponent, but rather a select committee of U.S. senators and investigators delving into the influence of racketeering within organized labor – in particular the International Brotherhood of Teamsters.

The chief counsel for the McClellan Committee – so named for its chairman, U.S. Sen. John McClellan, a Democrat from Arkansas – was a young Robert F. Kennedy, who in three years would become attorney general of the United States. That day, Kennedy planned to zero in on Davidson’s ties to one of the most powerful labor leaders in the country, James Riddle Hoffa, then the newly elected president of the Teamsters. During a previous hearing, Hoffa admitted to partnering with another Teamster official, Bert Brennan, to financially back Davidson in the early 1950s.

Facing the McClellan Committee – officially called the Select Committee on Improper Activities in the Labor or Management Field – wasn’t how Davidson wanted to spend his first year of retirement from the ring. At the time, he was living at 526 Belmont Ave. and was employed in the maintenance department at the Jewish Community Center on Gypsy Lane. Recently engaged, Davidson also earned a living as a musician in a local jazz band.

But it was Davidson’s earlier connection with Hoffa and the Teamsters that interested Kennedy. One question that especially intrigued investigators was how Davidson supported himself – he was living and fighting out of Detroit in the early- to mid-1950s – when he wasn’t earning prize money in the ring.

“I was in the face of how I was going to live from day to day when there weren’t any fights,” Davidson testified. “And so I asked Mr. Brennan for a job.”

Davidson testified he was set up on the Teamster’s payroll as a claims investigator at $75 per week, and his checks were drawn from the union’s welfare fund. “If one of the union members would call in sick or report off, it was my job to see if he was really sick and make a report of it,” he said.

“Did you ever do that?” Kennedy asked.

“No,” Davidson replied.

Hoffa had testified earlier that no Teamster funds were used to support Davidson. Yet to Kennedy’s frustration, Davidson would only implicate Brennan, and not Hoffa directly.

“Did you ask Mr. Hoffa about what your duties were to be as an employee of the welfare fund?” Kennedy queried. “No. I asked Mr. Brennan,” Davidson answered.

Indeed, the former heavyweight testified that he never received any money from Hoffa and would only see him on occasions when the Teamster boss inquired about how his training was progressing. “He treated me like a man,” Davidson told the committee, “and I in turn treated him like a man.”

Still, there was an air of nervousness toward the end of Davidson’s testimony, as he carefully navigated questions from the committee.

“What I say is the truth. I am not trying to involve anybody or harm anybody. I don’t want anybody to harm me,” Davidson said. “As far as I can, I am going to stand up for myself and protect myself.”

Davidson’s testimony contradicted statements he had given earlier to committee investigator Jim Kelly when he tracked the boxer down in Youngstown, Kennedy would write later in his book, “The Enemy Within.” Before his testimony, Davidson told Kelly that Hoffa knew of the arrangement with the welfare fund, and Kennedy thought it could lead to a perjury charge against the union boss.

Later, Kennedy spoke with Davidson in his office and asked him why he didn’t mention Hoffa’s role. “He told me frankly that he had been afraid to,” Kennedy wrote. Hoffa was present during the hearing and stared Davidson down as he entered the Senate Caucus Room, and Davidson felt intimidated. Moreover, Kennedy said he made the mistake of allowing Hoffa to sit directly behind the witness. As Davidson testified, Hoffa would often cough quietly. “This had upset him and he just didn’t want to talk about his former manager,” according to Kennedy’s account.

Although Davidson later delivered a sworn affidavit to the committee acknowledging Hoffa’s involvement, “I never again allowed Jimmy Hoffa to sit behind the witness chair,” Kennedy wrote.

Davidson was among several witnesses with connections to the Mahoning Valley during the course of the McClellan Committee hearings. In December 1958, the investigation turned to an inquiry over racketeering influence in the jukebox and vending machine industry.

Just two committee members were present during the morning session of Dec. 4: McClellan and Kennedy’s brother, Democrat John F. Kennedy of Massachusetts, who would less then two years later be elected the 35th president of the United States. Others on the select committee included Democrat U.S. Sens. Sam Ervin of North Carolina, Frank Church of Idaho and Patrick McNamara of Michigan, and Republicans Irving Ives of New York, Barry Goldwater of Arizona, Karl Mundt of South Carolina and Homer Capehart of Indiana.

Of interest was the influence of organized crime in the jukebox and vending machine business in the Mahoning Valley, according to testimony presented to the committee. Also, the committee placed a special focus on what Robert Kennedy and others deemed a rigged election at Teamsters Local 377 in Youngstown – one that favored a slate backed by Hoffa.

The meat of testimony on Dec. 4 came from investigators, not the alleged perpetrators, as at least one crucial witness refused to cooperate with the committee.

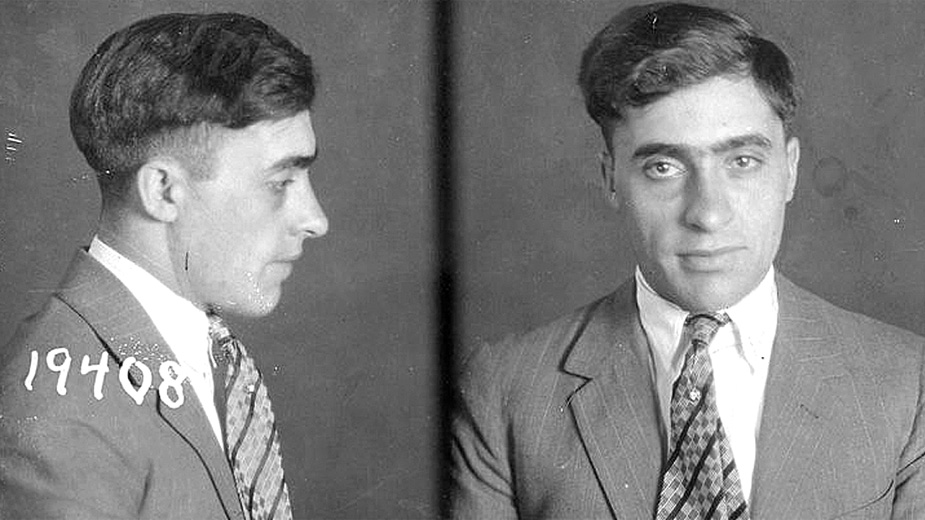

He was Frank Cammarata, who Frank Kaplan, the committee’s assistant counsel, described as having “a long record of association with most of the notorious hoodlums in the Detroit and Cleveland areas.”

Kaplan did much of the talking during the Dec. 4 hearing, as Cammarata refused to answer questions posed by Kennedy and the committee. Kaplan described a situation in Youngstown in which Cammarata was called in to break a “blockade” in the jukebox industry.

The situation involved an unnamed operator who was attempting to enter the Youngstown market with new Seeberg jukebox machines. However, the union – at the time the International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers – blackballed him, making it impossible for the operator to join the local affiliated with the jukebox industry. According to Kaplan, the operator complained to the police, since he “was subjected to a considerable amount of harassment and violence, stench bombs, window-breaking and such.” The Detroit-based distributor, Music Systems Inc., called on Cammarata for help.

By that time, the operator said he’d had enough, according to testimony, and walked away from the whole business. Instead, Cammarata moved in, took care of the trouble, and a relative of his took control of the Seeberg machine operation.

“Was there any difficulty after that?” Kennedy asked.

“They put 16 machines on location immediately,” Kaplan replied. Ultimately, the distributor moved its union affiliation to the Teamsters.

Cammarata was a career criminal that had deep ties and friendships across the region. In 1936, he was paroled in Michigan on the grounds authorities were to deport him back to Sicily. By 1939, he was back. This time hiding out in Ohio, according to Kennedy’s line of questioning:

Mr. Kennedy: “You came back in illegally, the second time, and you were in Ohio for the period of 1939 to 1946, when the immigration authorities found out about it. Is that right?”

Mr. Cammarata: “I refuse to answer on the ground I might incriminate myself.”

Indeed, Cammarata was able to dodge deportation for some time with the help of some powerful political allies – including U.S. Rep. Michael Kirwan, who represented the Mahoning Valley from 1937 until his death in 1970. On March 29, 1949, Kirwan introduced a bill in the U.S. House of Representatives calling for the attorney general to “cancel the deportation proceedings presently pending against Francesca Cammarata.”

Cammarata fled to Cuba one week after his appearance before the committee.

Kennedy also discovered that Cammarata had not filed a single income tax return between 1939 and 1946, yet had never been prosecuted or fined.

That prompted Sen. John F. Kennedy to chime in, “I wonder if it would be possible for the committee to obtain from the Internal Revenue, from the Treasury Department, their explanation of leniency shown to this witness,” as well as correspondence from all of those who might have tried to persuade the department to go easy on Cammarata.

Then once again, Robert Kennedy attempted to establish a link to Hoffa. Kennedy wondered why Hoffa attempted to intercede on Cammarata’s behalf to secure a pardon from the governor of Michigan when Cammarata was returned to the Michigan State Penitentiary in 1953. Cammarata refused to answer, a pattern that continued throughout his appearance before the committee.

Mr. Kennedy: “You have been in touch, Mr. Cammarata, with most of the most notorious gangsters in the U.S., in Miami, Las Vegas, Los Angeles and New York, have you not?”

Mr. Cammarata: “I refuse to answer on the ground that I might incriminate myself under the Fifth Amendment.”

Pictured: Frank Cammarata’s mugshot.

Kaplan then rattled off a list of criminals associated with Cammarata in the Youngstown area. The Farah brothers, who earned notoriety through their operation of The Jungle Inn, for example, had “alleged control of gambling, vice and illicit operations in Mahoning County,” he said. Mike Farah was eventually gunned down in Warren in 1961.

Five days later, on Dec. 9, the committee turned its attention to the testimonies of Larry Carelly and Joseph Sammartino, two members of Teamsters Local 377 in Youngstown who testified they were each wrongly ruled ineligible after being nominated to run against incumbent officeholders who Kennedy suspected were supported by Hoffa and William Presser, the head of the Ohio Conference of Teamsters.

Carelly testified that his candidacy was rendered ineligible because his union dues were not deemed in “good standing.” Yet, his testimony showed that all dues were automatically withheld from his paycheck over the last 15 years, and Sammartino was a member for 22 years without incident.

Once they were ruled ineligible, the matter found its way to Hoffa’s desk. Initially, it was communicated to Carelly that Hoffa had supported the candidates’ eligibility. However, the opinion turned against the pair once Presser intervened, investigators said.

“What obviously happened is that Mr. Presser is a very close associate of Mr. Hoffa’s, and Mr. Presser has the immediate jurisdiction over Ohio, and undoubtedly he intervened and stated that he did not want these gentlemen to be declared eligible,” Kennedy said. “And, so Mr. Hoffa reversed his position on this.”

In the end, despite a court challenge and a unanimous vote of the membership to place them on the ballot, the two were denied the opportunity to run against the incumbent slate, all of who were ruled eligible.

The testimony of Carelly and Sammartino was followed by an appearance by Joseph Blumetti, one of the incumbent officeholders in the Youngstown local. Blumetti refused to answer questions on the grounds of self-incrimination.

Ultimately, the McClellan Committee laid the groundwork for future legislative action against organized crime, including the Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations Act, or RICO. Moreover, it helped launch the public career of Robert F. Kennedy and factored prominently in John F. Kennedy’s bid for the presidency in 1960.

Hoffa too was vaulted into the national limelight, and was acquitted of charges brought forth against him based on evidence presented before the committee. But Hoffa was found guilty of jury tampering in 1964 and imprisoned in 1967. He was released in 1971 and then disappeared in 1975, presumably murdered by underworld figures.

Pictured: Robert F. Kennedy consults with his brother, Sen. John F. Kennedy, during a session of the McClellan Committee hearings.

Flashback is sponsored by Hickey Metal Fabrication in Salem.

Copyright 2024 The Business Journal, Youngstown, Ohio.