This year will see more varieties of electric vehicles on dealership lots than ever before, setting up what one industry analyst calls a “pivotal year” for the segment.

Lordstown Motors Corp. expects to deliver its first Endurance pickup later this year. Ford is introducing the Mustang Mach-E, an electric SUV version of its legendary muscle car. Mercedes-Benz will put out the EQC, an electric-powered luxury SUV. Next year, General Motors will release the Chevrolet Bolt EUV and the GMC Hummer EV.

Looking down the list of EV models arriving soon, it’s easy to pick out the trend: no longer are electric vehicles largely limited to sedans. Now, the most popular segments in America – trucks and SUVs – are getting the electric treatment.

“The fact that we’ll see more affordable SUV options – which is the predominant body style in the United States – gives people the type of car they want,” says Jessica Caldwell, executive director of insights at auto industry analysis firm Edmunds. “2021 probably won’t see a massive spike [in sales], but I think this is where the trend starts. This is still a crazy year with COVID, so there may be delays or other issues, but it feels like a new beginning for electric vehicles.”

Since battery-powered cars and hybrids first started gaining popularity, they were primarily limited to subcompacts and sedans. That was largely because of the technology available, says Stephanie Brinley, principal automotive analyst for IHS Markit. It takes more energy to move bigger vehicles like SUVs and trucks and their designs are less streamlined, increasing drag and further increasing power needs.

“For trucks, you also have an owner that has different demands. You have offroad. You have towing. You have work capabilities that those trucks need to deliver. Customers are very confident and comfortable in their [internal combustion engines]. You have to prove that this can work,” she says. “If you can’t deliver the capability, they won’t accept it. The first models have to prove that it can do everything an [internal combustion engine] truck can do.”

For startup automakers like Lordstown Motors, that’s both a blessing and a curse. More options in the electric market mean more awareness of products and their capabilities, which down the road could turn into more sales. But it also means competing with the likes of GM, Ford and Ram, long-established manufacturers – all of which have announced electric trucks of their own – that have decades of customer loyalty and experience.

“They’re confident they can deliver that. I don’t think they’d be as bold in their steps if they weren’t. It’ll be a long time before you convince all 900,000 F-Series buyers a year to switch to electric, but you can make a dent,” Brinley says.

The key to the success of an endeavor like Lordstown Motors or Rivian – another electric-powered truck startup – lies in finding a niche “off-center,” she continues. Lordstown Motors is targeting the work truck segment and offering only fleet sales for the foreseeable future. Rivian, meanwhile, is developing models that are “lifestyle-oriented and a little more expensive that you can take offroad for an adventure.

“They’re not going against each other and they’re not going head to head with Ford or GM,” she says.

But there is still competition in the EV market. Adjacent to Lordstown Motors’ assembly plant, Ultium Cells LLC, a joint venture between GM and LG Chem, is building a $2.3 billion battery plant and is considering a second site for another Ultium plant, likely in Tennessee. In total, GM has committed $20 billion to creating a zero-emission lineup, a plan that relies heavily on Ultium battery cells.

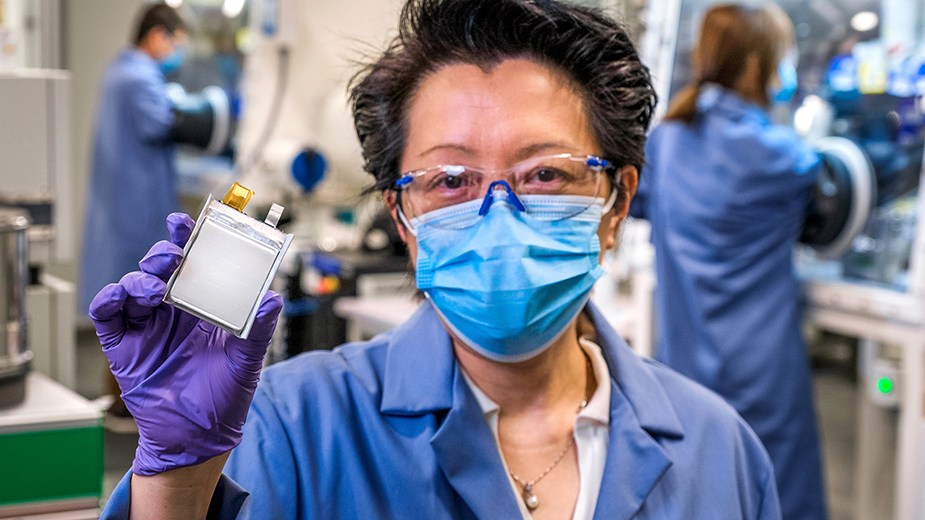

GM R&D Group Manager Mei Cai, Ph.D., holds a prototype second-generation Ultium battery cell. (Photo by Steve Fecht for General Motors)

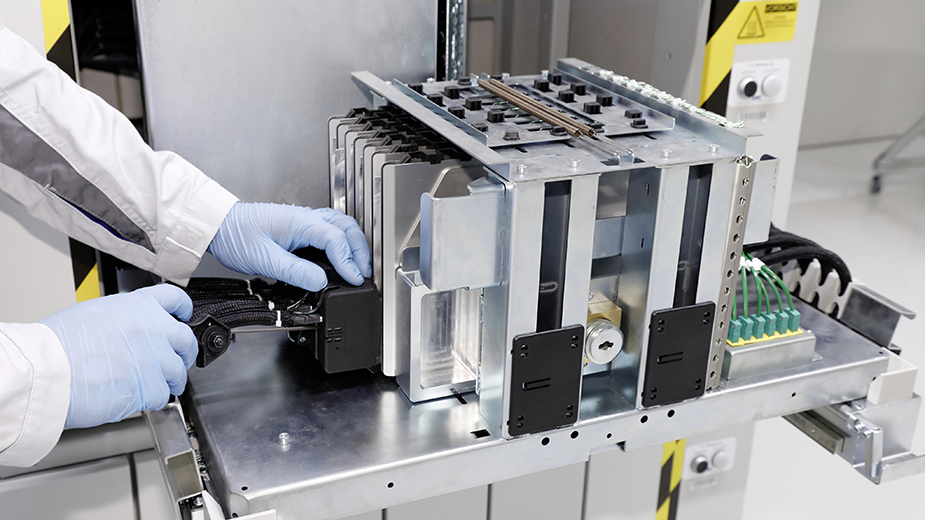

This model shows how Ultium batteries will fit into GM’s electric vehicles. (Photo by Steve Fecht for General Motors)

In Michigan, construction is underway on Ford’s Rouge Electric Vehicle Center. The plant, on a site where the automaker has built cars since the late 1920s, is expected to produce the first electric-powered F-150s in 2022. Overall, Ford is investing $700 million in remaking its F-Series lineup, a move that includes the creation of EV and hybrid models, and more than $20 billion to its electric offerings as a whole.

“The smaller automakers that took pages out of Tesla’s book and said, ‘We’ll take our design a little ways over here and our technology a little over there to be unique.’ That’s not proving as easy as it was six or seven years ago. There’s a tougher time to break in now,” Brinley says.

The move toward electric-powered trucks and SUVs will close the gap between what consumers want and what manufacturers are producing. In a report released in January, IHS Markit reported that SUVs and crossovers accounted for more than half of the American auto market, with trucks around 20%.

“The reality is that people want to consume EVs as they do the rest of the market. They want many offerings, many sizes, many price points,” Caldwell says. “It needed to reflect the market as a whole to gain success.”

The shift could mean greater loyalty to the segment. According to research by Edmunds, 71% of EV owners who didn’t return to the segment traded in their vehicles for trucks or SUVs in 2020, up from 60% in 2019 and 34% in 2015.

“A lot of people just left the electric vehicle segment and went to an SUV or something larger. That told us that for electric vehicles, their size wasn’t meeting consumer needs,” Caldwell says. “The fact that more automakers are introducing different sizes of EVs means there’s a better chance of keeping them inside your brand. Once they’re inside, it’s up to you to lose them. They know their dealer and people are notoriously shy about changing brands.”

As a whole, one of the largest hurdles to widespread adoption of electric vehicles remains infrastructure. Charging stations aren’t yet commonplace in many areas and even where they are, there are still capacity issues. Caldwell points to places like Los Angeles, where EVs are popular but the region encounters brownouts during warmer months as the power grid is strained.

“I can only imagine having three cars in the family and trying to charge those along with running the AC. It’s something we seriously have to look at as a society,” she says. “I live in Los Angeles and although the [electric vehicle] infrastructure is decent here, there’s still lots of talk about broken public chargers or, before the pandemic, Tesla charging stations being packed with a long line.”

But, she and Brinley agrees, EVs are the future for automakers large and small. Whether companies like GM are committing billions of dollars to their efforts or those like Lordstown Motors are working to revamp assembly plants for their efforts, all are making long-term efforts in the field.

“The Lordstowns, the Rivians, the small truckmakers, they’re not expecting that their vehicles will be 80% of U.S. volume in two years,” Brinley says. “They know that this is a long-term play and that they’re in for a decade or 20 years to transition, maybe longer.”

Pictured at top: Ford has built vehicles at its River Rouge Complex in Dearborn, Mich., for more than a century. This rendering shows what’s coming next to the site: the Rouge Electric Vehicle Center and an electrified version of the F-Series lineup.