By Pat Springer

YOUNGSTOWN, Ohio – Whether talking about a daily driver or a modified American muscle classic, cars and emotions – in song, art and life – have been intertwined since they first hit the road over a century ago.

They have also left a lasting imprint on the design of our environment and for both better and worse, have fundamentally reshaped the ways in which we live, work and enjoy ourselves.

Our fascination and love affair with cars began in the 1880s when Karl Benz and Gottlieb Daimler produced their engine technology that would forever change the world.

In the first decades of their existence, automobiles were primarily playthings for the well-heeled and adventurous.

Nobody bought one to commute to work or run errands. But for those who could afford them, cars offered an intoxicating and thrilling experience that raised questions about how they could radically transform our lives.

More than a hundred years later, however, the disruptive technology of mainstream electric vehicles raises these same questions.

How will a car that requires less maintenance yet offers the latest innovative features impact the entire automotive ecosystem – manufacturers, dealers, suppliers, and most of all the customer?

As Ford, Mercedes, General Motors and Volkswagen announce billion-dollar investments to produce new electric and plug-in hybrid electric vehicles, will their results once again revolutionize the way we move?

‘AUTOMANIA’ AS MODERN ART

Automania, a current exhibit at The Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York City, presents an informal history of how we arrived at our current situation.

The exhibit examines cars from years past both as cultural style icons and industrial products and addresses their adverse impact on roads and streets, public health and the planet.

Inside the museum are paintings, photographs, drawings, sculptures, and the nine on-display cars selected to make up the exhibit.

It’s hard to imagine a future world of cars stripped of driver responsibilities and control when looking at these vehicles that were so much fun to drive and became such a part of our culture.

Taking its name from the 1963 animated dark film “Automania 2000,” which satirically looked at our automobile obsessed consumer culture, the exhibit is more whimsical and fun.

After working a decade for a global automotive company that sells parts and accessories to make cars go faster and look pretty, I consider myself a novice gearhead and looked forward to seeing the exhibit in person in late October.

‘BEETLE’ TAKES A STAR TURN

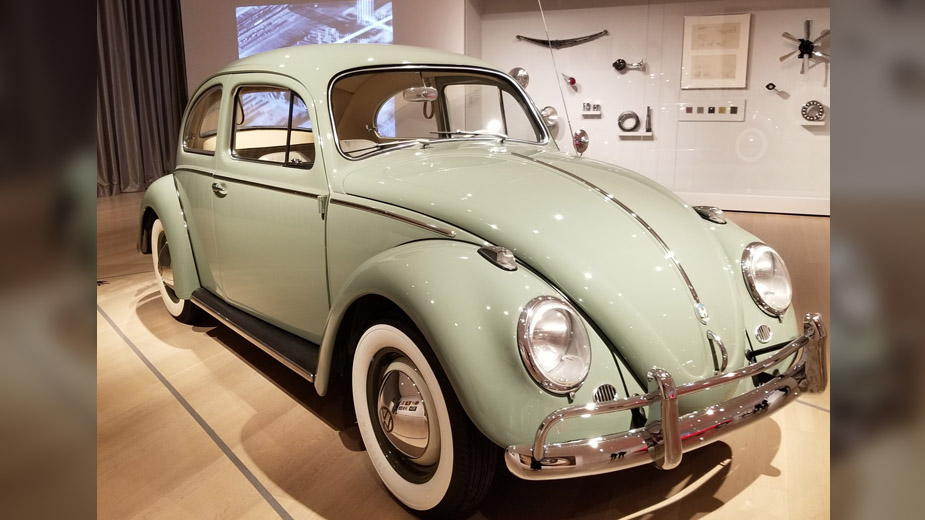

The star of the show is a restored 1959 lime green Volkswagen Sedan Type I, also known as the “Beetle,” “Bug” and in Germany, the “people’s car.”

At the 1933 Berlin Motor Show, Adolf Hitler’ declared, “A nation is no longer judged by the length of its

failings but by the length of its highways.”

This challenged German automakers as Hitler envisioned a future for Germany paved with asphalt and filled with private automobiles.

Introducing a plan to produce a car affordable for the middle and lower classes, Hitler tasked the manufacturers to build a vehicle capable of accommodating up to four people and maintaining a speed of 60 mph.

The result, despite its shameful origin, became one of the most famous cars ever produced.

Designed by Ferdinand Porsche in 1938, it was mass produced more than 20 million times on an assembly line. It became a cultural icon in the United States, a symbol of the 1960s counter-culture movement. In 1972, it surpassed Henry Ford’s Model T as the best-selling car of all time.

The Beetle is the car baby boomers grew up with. We drove it with no air conditioning in July (it was air-cooled) and no heat in freezing February.

Despite its frugality, it was reliable and charming and has evolved from a daily driver into a much sought-after collectible.

RADICAL DESIGN, Hand Made

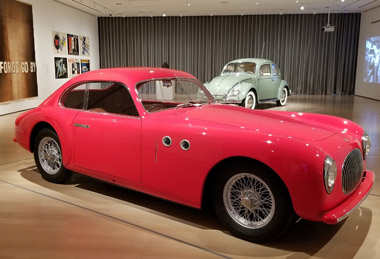

If the VW bug became a car for the masses, then the Cisitalia 202 GT exists as one of the rarest ever built. Designed in Turin, Italy, in 1946 by Battista “Pinin” Farina, archives show that only 170 Cisitalia models were made. Its small production run resulted in part from the handmade qualities of the car.

In a process held over from the horse-drawn carriage trade, the body panels were hammered out over wooden forms as opposed to being stamped by machines.

Pininfarina’s radical design eschews the ornamentation and separation of parts typical of cars of the period in favor of a unified structural skin.

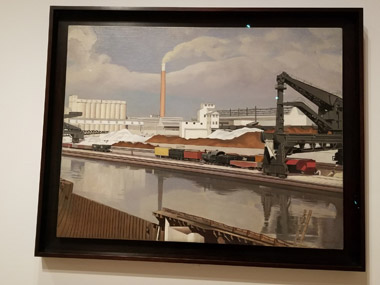

At the same time, however, in the United States, Henry Ford was proving that his system of parts produced on the assembly line, a spectacular form of industrial capitalism, drove efficiency and boosted capacity.

No figure had a greater impact on automobile manufacturing – and modern industry. At the heart of Ford’s program was the River Rouge factory complex in Dearborn, Michigan.

Completed between 1917 and 1928, workers there manufactured standardized parts for utilitarian vehicles like the Model T that made car ownership available to the masses. Indeed, some of these car parts, pistons, ball bearings and headlamps, are included in the exhibit.

FUTURISTIC FLOURISHES

During the 1950s, sales in the United States boomed in large part because of the emerging middle-class consumer. To stay competitive, each year manufacturers, began to introduce updated models. They offered cars in a range of colors and with futuristic space age flourishes such as tail fins.

In the United Kingdom, a large production passenger car emerged as both a cutting-edge racing car and a luxurious passenger vehicle. The Jaguar E-Type Roadster (the XK-E here), designed by a British trio in 1961, was fast.

The Jaguar Roadster could reach 62 mph in less than seven seconds. Its sleek steel unibody was sexy and attractive to film producers, who put it in countless James Bond movies

The technological optimism of automobile mass production, though, began to wane during the late ’60s.

While the automobile industry had driven the post-war economic boom and improved our standard of living, its positive impact was becoming overshadowed by the problems that came with a car-centric world – clogged traffic, smoggy cities, suburban sprawl, the displacement of communities by highways, and escalating fatalities.

Cars made suburban living possible, resulting in a nationwide urban flight. They also made mass leisure possible. The summer vacation became an annual ritual for many families as they hauled the classic Airstream Clipper behind their station wagons.

Designed and built by Wally Byam, who had worked in aircraft factories during World War II, he named the Clipper after the first trans-Atlantic seaplane.

Incorporating aerospace rather than home-design elements, Byam built the Airstream to provide more comfort when people camped.

The model in the photo below, designed in 1963 and wrapped in aluminum, is called the Silver Bullet. Displayed with its door open, taillights on, and windows propped open, it appears to have just been parked at a campsite.

Mitigating the harm wrought by cars while still accommodating and embracing them is a challenge that continues to this day, troubling planners, architects, environmentalists and political leaders worldwide.

The exhibit runs through Jan. 2. Museum of Modern Art, 11 West 53rd St., New York. Open daily 10:30 a.m. to 5:30 p.m. COVID-19 vaccinations (age 12+) and masks (age 2+) are required.

Pictured at top: Volkswagen Type 1 Sedan. Manufacturer: Volkswagenwerk AG, Germany, 1938.