YOUNGSTOWN, Ohio – Most residents know The Butler Institute of American Art as the treasured centerpiece of culture in the Mahoning Valley – a gallery that houses the works of some of the most important American artists across four centuries.

Few know the man behind this legacy.

Indeed, as Joseph Lambert Jr. and the late Rick Shale point out in their book, “First Citizen: The Industrious Life of Joseph G. Butler, Jr.,” the Youngstown museum’s ornate marble façade “bears his name but not his story.”

It’s this void that the authors fill with the first in-depth biography of this prominent figure.

Throughout the book’s nearly 200 pages, the reader bears witness to Butler’s life as the Mahoning Valley undergoes its seismic transformation – from the mostly agrarian and early iron works economy of the 1840s to the region’s rise as a steelmaking powerhouse during the latter half of the 19th and early 20th centuries.

“I just thought this made for an exciting story,” Lambert says of his interest in Butler and his life. That interest began more than 30 years ago, when the co-author worked at the Youngstown Historical Center for Industry and Labor as that institution prepared to open its doors.

“All kinds of information was coming in,” he recalls. Among the recurring names that stood out as the museum was gathering its collection was Joseph G. Butler Jr. “I wanted to learn more about him.”

The result was several decades of research that incorporated Butler’s personal correspondences, books and articles he’d written, papers, ephemera, documents, newspaper articles, as well as secondary sources that provided valuable context of the time period.

Lambert, a nursing home administrator for Windsor House Inc., holds a master’s degree in history from Youngstown State University. Co-author Rick Shale, a former professor who taught in YSU’s English department, signed on to the project nearly 10 years ago to help craft Butler’s narrative.

Shale died in February 2022, just after McFarland & Co. accepted the biography for publication. “First Citizen” was published later that year.

Butler’s Formative Years

Butler was indeed a man of his times, Lambert says. He was born in 1840 to a modest household in Mercer, Pa., the son of Temperance and Joseph Green Butler Sr., who operated a small iron blast furnace. After struggling with that venture, the family relocated to Niles, Ohio.

It was here that Butler’s father took a position to manage the company store for James Ward & Co., a rolling mill operation. At age 13, Butler left school and joined his father as a clerk in the company store.

The experience in Niles led to friendships that would alter the course of Butler’s life, especially a close relationship with the Ward family. When Butler’s father relocated to Warren after being elected to county office during the 1860s, for example, Butler stayed with the Ward family in Niles to learn more about the iron business. It was also in Niles during the 1850s that the future industrialist began a lifelong friendship with future U.S. President William McKinley, whose father was a former business partner with Butler Sr.

“He rose from very humble beginnings through hard work and dedication to his profession,” Lambert says. “He had limited education, but he was a man who took advantage of opportunities that came his way.”

It was under James Ward’s tutelage that Butler became a seasoned student of operations and management.

After devising a process that significantly reduced waste in the iron-rolling process, Butler was promoted to bookkeeper. Then, he was offered the position of office manager where he would shepherd the company’s financial operations.

He left James Ward & Co. to work as a sales manager for an iron shipping company in Chicago, before returning to the Mahoning Valley as an investor in one of that company’s ventures in Youngstown.

After the Civil War, Butler struck up a friendship with former Ohio governor and Youngstown resident David Tod.

In many ways, Tod became a second mentor to Butler as he and other investors, including James Ward’s brother William, established the Girard Iron Co.

Thus began a career in the iron and steel industry that led Butler to interact with some of the biggest financiers and industrial titans of the era. Andrew Carnegie, Charles Schwab and Henry Clay Frick were all contemporaries who knew Butler well.

It was one of Frick’s early coke operations in Connellsville, Pa., for example, that fed the Girard Iron Co.’s blast furnace.

As such, the company became the first in the Mahoning Valley to manufacture pig iron from coke.

Frick later earned notoriety as the Carnegie surrogate who many historians agree precipitated the Homestead Steel crisis of 1892.

Lambert emphasizes that Butler was not as cutthroat as his wealthier contemporaries.

“A lot of those characters that emerged were kind of ruthless,” he says, as many resorted to violence to suppress strikes and kept wages low for the working class.

“You never got the impression that Butler was made that way,” Lambert says. “He was a person I thought who differed from the others.”

While he was certainly sympathetic to management during periods of labor strife, Butler was “someone who got amongst the people,” Lambert says, citing the numerous charitable causes he spearheaded during his lifetime.

It was Butler who persuaded Carnegie to donate the final $50,000 toward the construction of a new public library in Youngstown, Lambert says. “Even though Carnegie was building libraries across the country at this time, his stipulation was that the library had to be named after him.”

Instead, the Youngstown library was named for educator Reuben McMillan.

Political Influence

Butler’s rise in the iron and steel industry also corresponded with his emerging political clout.

“Butler was always a Republican, as was his childhood friend William McKinley,” Lambert says. “When McKinley ran for governor, Butler helped him out in his campaigns and the presidential campaigns of 1896 and 1900.”

Butler served as a delegate to three Republican presidential conventions, including the 1920 convention that nominated another friend, U.S. Sen. Warren G. Harding.

“He built a network within the iron and later steel industry, but also within the Republican National Committee,” says Bill Lawson, director of the Mahoning Valley Historical Society.

If you were a Republican office seeker and stumped in the Mahoning Valley, the candidate’s likely first visit was to see “Uncle Joe,” as Butler would be affectionately called. “He had a very fatherly presence both here in our community and in the Republican Party statewide during the early 20th century,” Lawson says.

Other major political figures of the late 19th and early 20th centuries expressed gratitude and deference to Butler, according to Lambert.

“When William Taft ran for president, his official campaign opened and closed in Youngstown because of Joe Butler,” Lambert says.

Butler also paid close attention to local politics and sat on Youngstown’s first city council.

Butler’s Legacy

While Butler accumulated great wealth, he didn’t live extravagantly. Rather, Butler spent much of his money on community causes and his passion for collecting art.

“Butler early on in his life takes an interest in art,” Lambert says. Later in his career, when Butler had the means to travel, he frequently visited the renowned art galleries of London and Paris.

“What struck him on all those travels was the lack of representation of American artists,” Lambert says.

His art collection was stored on the third floor of his family’s Wick Avenue house – where the McDonough Museum stands today – while some of his collection was often displayed at the public library, Lambert says.

Butler then began contemplating constructing a permanent home for his collection and the collections of others, and put in motion plans to build what would become The Butler Institute of American Art.

A house fire would subsequently destroy approximately 100 paintings in Butler’s collection but that didn’t deter him from completing his museum. Despite construction delays, the art museum opened Oct. 15, 1919, during a private ceremony. The artwork displayed then was valued at an estimated $500,000.

Butler’s original portraits of Native Americans and the American West survived the house fire and remain part of The Butler’s permanent collection on display.

Butler also spearheaded the drive for the construction of a permanent memorial to his old friend McKinley, who was assassinated in Buffalo, New York, in September 1901.

The National McKinley Birthplace Memorial was dedicated Oct. 5, 1917. An estimated 10,000 guests attended. Among those who contributed funds for the project was none other than Henry Clay Frick, who donated $50,000.

“I think the most interesting part of Butler for me is just what a Renaissance man he was,” the history society’s Lawson says. “He was an industrialist. He didn’t have a formal education above the grade school level. He studied and appreciated art, and he was an archivist for the community.”

He was also an author. As a historian, Lawson says Butler’s most significant work is his three-volume “History of Youngstown and Mahoning Valley,” published in 1921. “Still, a century later, it’s one of the gold standard publications for understanding our region’s history,” Lawson says.

In December 1919, Butler was returning from Pittsburgh after attending the funeral of Frick. As he crossed Wick Avenue at the intersection at Rayen Avenue, a motorist struck Butler.

Although he recovered from the accident, friends would say that the accident severely impaired the 78-year-old and observed he would never be the same. Butler died Dec. 19, 1927, one day shy of his 87th birthday.

Lambert says he hopes his book helps to enlighten local readers about the life and career of Butler.

He recalls a craft show last December at The Butler, where Lambert had set up a table with books for sale.

“I had people coming up to me, looking at the book, saying ‘Who’s this guy?’” Lambert says incredulously. “Butler needs to be in our historical memory, our historical conversation. There’s no reason why we shouldn’t know about him.”

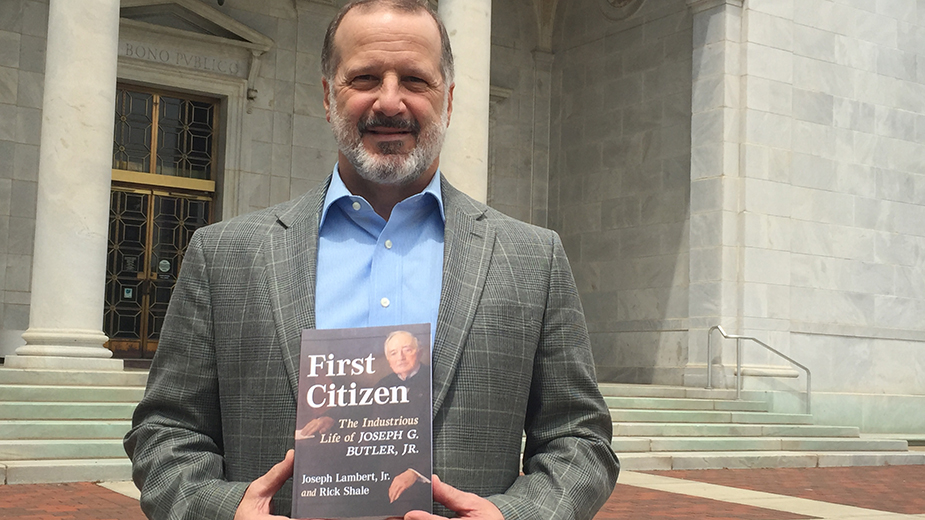

Pictured at top: Joseph Lambert Jr. holds a copy of “First Citizen: The Industrious Life of Joseph G. Butler, Jr.”