YOUNGSTOWN – Dyonn Perry is a good student. He’s self-motivated, embraces his studies and is eager to please his teachers.

On a chilly afternoon in February, Dyonn is at his book-strewn kitchen table peering into a laptop as he works on a project about Harriet Tubman, the Black abolitionist who personally led dozens of slaves to freedom during the mid-19th century.

The sixth-grader at Harding Elementary School in Youngstown says he enjoys English and reading but admits this year he’s struggled with several subjects that he thinks he could master were he in a traditional classroom.

“I get frustrated easily on some subjects,” he says. “I’d rather be in a classroom where I could focus better and listen to my teacher.”

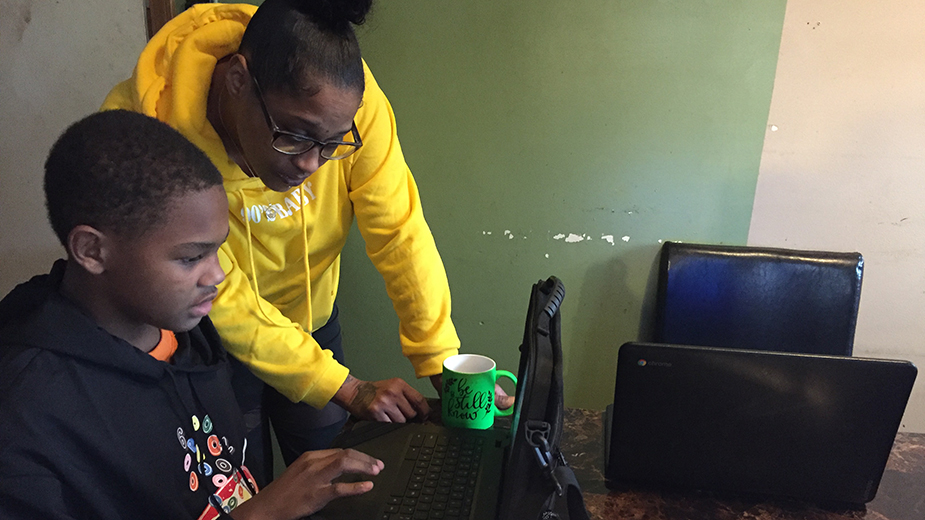

Dyonn is among thousands of students who over the last year have adapted to remote learning brought on by the COVID-19 pandemic. His brothers, Jyonn, a fifth-grader at Taft Elementary, and John, a sophomore at East High School, have documented learning disabilities, making remote education even more difficult and complicated for them, says their mother, Jasmine Hyde.

“It’s killing my 10th-grader,” she says. “It’s caused him to lose interest and I’m finding it harder to motivate him. He’s a social butterfly and misses being in school.”

All of Ohio’s public school districts pivoted to remote education classes in March of last year per Gov. Mike DeWine’s orders as the pandemic tightened its grip across the state. Most districts have since opened up face-to-face instruction through either a hybrid model or full attendance, as the state steps up its vaccine program.

According to the Ohio Department of Education, just 10 of the state’s 609 public school districts, including Youngstown, remained fully remote as of Feb. 23. The district has since announced it would allow students enrolled in pre-kindergarten through first-grade – as well as those with multiple disabilities and autism – to return to classes two days a week beginning March 23.

Beginning April 13, second- through fifth-graders will return for in-person instruction on Mondays and Fridays. Students will continue to participate remotely on days that they are not scheduled to attend.

Families, however, will still have the option of keeping their children home and implement remote instruction full-time. The school district has not determined when in-person classes would resume for grades six though 12.

For mothers such as Hyde, the prospect of her children returning to the classroom brings them a sense of hope. Her 10th-grader has an individual education plan, or IEP, and his tutor has helped to fill in the gaps that he needs to complete his schoolwork. But the family’s internet bandwidth is often clogged since all three boys are working online simultaneously, she says.

“It lags a lot,” Hyde says. “With all the children on it at once, it’s not good.”

There are some benefits to online instruction, she admits. Since she was placed on layoff from her job last year, Hyde has been able to spend more time with her children and take a more active role in their education. “I’m involved either way, in-person or online,” she says. “If there’s a silver lining to this, I know my kids are safe every day.”

Even so, there are early signs that the pandemic could take a serious toll on younger students. According to a report released in January by Vladimir Kogan and Stephane Lavertu of Ohio State University, the statewide results of the Third-Grade English Arts Assessment shows a significant drop in proficiency compared to 2019.

The tests are administered twice a year, once in the fall semester, the other at the end of the school year. The second proficiency test determines whether the student is able to advance to the next grade.

The study found that overall scores in the fall test dropped by the equivalent of one-third of a year’s worth of learning compared to 2019. For Black students, that number declined to about one-half, the report shows.

While the study cited remote learning as a potential reason for this decline, it emphasized other factors brought on by the pandemic, such as sickness, death or job loss. It also cautioned that the study was limited to one subject and one grade so a full scope of how COVID-19 has affected overall education across the state might not be fully understood until other assessments are completed later this year.

Youngstown City School District CEO Justin Jennings says that although participation in this year’s third-grade reading assessment is higher than in 2019, overall scores were lower.

“The scores weren’t as high as they’d been in the past,” he says. Jennings could not provide specific data as to how much they had declined.

Jennings says he’s received emails from parents still nervous about sending their children back to the classroom amid the pandemic. Often, an elderly family member may have a compromising health condition that places him at high risk for COVID. Or, parents are uncomfortable about their children returning to the classroom without a vaccine.

“I’m getting a lot of that,” he says.

Jennings says the district’s reopening plan is based on recommendations from the Centers for Disease Control, which suggests that schools in high-risk areas remain virtual for older students. Attendance rates in Youngstown have also been affected throughout the course of the pandemic.

Last semester, attendance across the school in the district was down about 10%, says Jeremy Batchelor, chief of staff.

“We were at 81.4% attendance in the fall compared to 91% the same time last year,” he says. Much of the attendance leakage, he says, was evident during the afternoon, when students wouldn’t return from lunch.

“It’s not ideal but we’re making it as palatable as possible,” he says. “The schools and teachers are doing the best they can.”

Batchelor says he understands how hard it is for students and teachers alike. He underscores the importance of returning to the classrooms safely. “This has been a tough time,” he says. “We want to get back in the building full-time, but also want to be safe.”

As of now, the third-grade assessment is the only measurement that exists on student performance, says Traci Hostetler, superintendent for the Mahoning County Educational Service Center.

“We’re not sure yet what results COVID is going to have on our kids,” she says. “Right now, we’re making our best educated guess.”

What is clear is that administrators, teachers and others worked diligently over the summer to prepare flexible plans to conduct classes during the pandemic, which intensified over the early winter, Hostetler says. “It was quite refreshing to see, at an ugly time, how everyone was empowered to make sure the kids were prepared as they could be.”

That included Zoom sessions between teachers and administrators to acclimate them to new technology intended for the classroom, says John Kuzma, director of teaching and learning at Mahoning County ESC. “During the summer, we had close to 1,800 teachers attending different sessions.”

Challenges remain, Hostetler says, including improving internet access in underserved portions of the county. However, the rollout over the fall pales in comparison to the demands placed on school systems in March 2020, when administrators, teachers and students had two days to completely overhaul their learning platforms.

“The difference between March and August of 2020 was night and day,” she says.

Nevertheless, remote education doesn’t provide the type of hands-on collaboration necessary between students and instructors, Hostetler says. “We’re losing that,” she says. “It’s much more conducive to solve a problem in the classroom than in a room by yourself. So, our kids were missing out.”

There’s also evidence that the impact from COVID has infiltrated much further than students’ academic performance, says prevention coordinator Ashley Mariano, who coordinates mental health at Mahoning ESC. “We see depressive symptoms increasing,” she says. “The anxiety in children and adolescents is very prevalent.”

It’s still too early to determine what long-term effects the pandemic will have on students, Mariano says. “I’m trying to help teachers understand the tenets of prevention and act as a family liaison to the district for students,” she says. The goal is to identify any at-risk students early and then direct the proper resources to help them.

Key is collaborating with organizations such as the mental health recovery board, school prevention programs, even food and nutrition services across the region, Hostetler says.

On one end, students are already anxious over pressure from parents who overwhelm them with work and activities. Then, there are students who are stressed because of gunshots in their neighborhoods or insufficient food in their houses, she says.

“Kids have always been stressed and this pandemic hasn’t helped,” Hostetler says. “We’re trying to reach these kids proactively, instead of reactively after the pandemic. The biggest risks are those kids with higher external stressors and the lack of parental support.”

In Columbiana County, all of the school districts have returned to in-class learning, says Anna Marie Vaughn, superintendent of the Columbiana County Educational Service Center. “I saw a lot of students anxious to be face-to-face,” she says. “They just wanted to be there.”

School districts across the county participated in other measures to help alleviate the pressures of COVID, Vaughn says. “We needed to get equipment out to students,” she says, as well as providing other services. “We had days where parents could drive through and feed students breakfast and lunch,” she says.

A broadband connectivity grant helped to expand internet service in some of the more rural areas in Columbiana County, Vaughn says. This is likely to accelerate the integration of new technology into the classroom, then push it out to students across their respective districts. Professional workshops extended to teachers are likely to continue long after the pandemic.

“We’ve seen huge steps in that area,” she says.

For other institutions, making the transition to fully remote education this academic year was never an option.

“Being a tech center, we can’t go remote,” says John Zehentbauer, superintendent of the Mahoning County Career and Technical Center in Canfield.

Much of the education is hands-on through lab courses, Zehentbauer says, since assessment in these classes depends on a student’s in-class performance and aptitude. To alleviate concerns over the pandemic, MCCTC would hold in-class labs on Monday and Wednesdays for seniors, and Tuesdays and Thursdays for juniors. Students would then move to remote learning for their academic courses, he says.

“These students come to us for hands-on learning,” he says. “So it’s tough for these kids.”

More important, in-person instruction is vital in developing the skills of a young person looking to pursue a career in his field, whether in public safety, industrial welding and maintenance, trucking, or EMT professions, Zehentbauer says.

“Our business and industry partners have pushed us,” he says. “Not making these kids employable is not an option.”

Pictured: Jasmine Hyde helps her children, Dyonn, Jyonn and John. She’s concerned about how much they are learning.