YOUNGSTOWN – Key to the sustainability of companies such as Lordstown Motors Corp. and Ultium Cells LLC is procuring the very materials necessary to develop electric-vehicle battery and motor technologies.

And it all begins in the ground.

Rare-earth elements used in magnets for electric motors and metals such as cobalt and lithium used in lithium-ion batteries, are critical materials for the next generation of EVs. However, most of these materials are processed and mined overseas, creating a potential challenge to the supply chain as the auto industry electrifies.

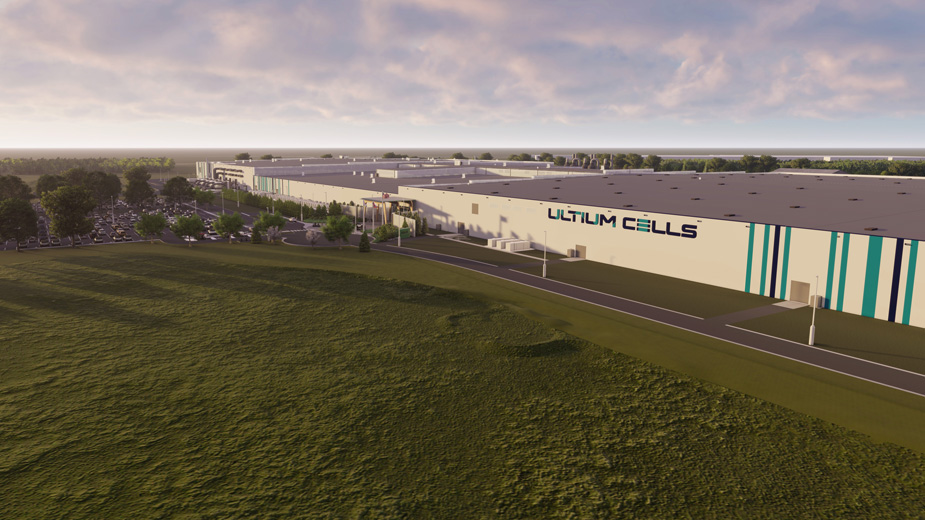

By September, the first commercially produced all-electric pickup should be rolling out of the former General Motors Lordstown assembly plant, now owned and operated by Lordstown Motors. By the middle of next year, the first electric-vehicle battery cells will begin to ship out of Ultium Cells LLC’s new $2.3 billion plant in Lordstown.

Both ventures are pioneering battery and electric-power technology, making access to rare earth and critical metals essential to their success.

“The supply chain is dominated by China now. But it doesn’t have to be,” says Robert Schoenberger, editor of Today’s Motor Vehicles, a publication that tracks the automobile industry. “They’re just coming out of China now because China is the only country really pushing electrification on a scale that requires it.”

Yet as demand for electric vehicles increases in the United States – General Motors has pledged to commit its entire product portfolio to zero emissions by 2035, for example – the need for these materials will likely motivate the development of a domestic supply chain, he says. At the same time, chemical engineers and scientists are researching ways that could reduce the content of rare earths or cobalt in electric vehicles, making U.S. producers less reliant on foreign sources.

“At this point, it’s looking like the biggest bottlenecks in the system aren’t going to be from Tesla, Ford or GM having the cars to provide,” Schoenberger says. “It’s going to be the supply chain.”

Given the anticipated growth of the EV market, Schoenberger says that even China’s output is insufficient to satisfy projected demand in the United States over the next 15 or 20 years.

Manufacturers such as Tesla have demonstrated there is a market for EVs in this country, he says. The discussion has now shifted to adopting a policy that could help to support domestic production of these raw materials or to establish a reliable network with stable and friendly governments as a source, Schoenberger says.

President Joe Biden’s “China-Free” initiative could be a first step in that direction. Biden signed an executive order Feb. 24 that calls for a 100-day review of products where domestic manufacturers depend on imports. These include high-capacity batteries, semiconductors, and critical and rare earths. The initiative has received bipartisan support.

Rare earths aren’t exactly scarce. They are, however, expensive to extract, Schoenberger says. These elements are found in magnets used in electric-vehicle motors, not unlike the hub motors on Lordstown Motors’ Endurance. As of now, more than 80% of these elements are imported from China, according to the U.S. Geological Survey.

Schoenberger says Lordstown Motors’ hub-motor platform – the truck will carry motors for each wheel, all synchronized by software – could be a game-changer for the entire industry.

Other elements such as cobalt, nickel, graphite and lithium are also abundant. But China remains dominant in mining graphite and nickel and has a sizeable market share of chemical processing all of these materials.

For example, China processes 100% of the world’s graphite, 80% of the world’s cobalt, 51% of the global lithium supply and 33% of nickel, says Dan Sawmiller, Ohio energy policy director for the Natural Resources Defense Council.

“It’s a serious concern when you think about the need to source these materials domestically,” he says. “The U.S. is, frankly, behind.”

Controlling the supply chain, Sawmiller says, is vital to the new EV industry and Ohio could play an important role in securing a healthy part of it. Cobalt, for example, is needed for cathode and anode production – manufacturing that could easily be performed in Ohio because of an already existing automotive supply line.

“We’re an automotive powerhouse,” he says. “We’ve got recycling, renewable energy that these companies want.”

The driving force is Ultium, a joint venture between GM and Korea-based LG Chem which is constructing its nearly 3 million-square-foot EV battery plant along Tod Avenue in Lordstown, Sawmiller says.

While mining for critical materials is not likely Ohio’s strongest contribution in a prospective supply chain, chemical processing, cathode and anode production, and battery cell manufacturing certainly are, Sawmiller says. Moreover, electric-vehicle production evidenced by Lordstown Motors exemplifies a finished application of the product.

Cathode and anode production – or the positive and negative terminals on a battery – represents some of the biggest job-intensive and tax revenue creating pieces of the supply chain, he says. At present, no cathode or anode production occurs in the United States. China commands 82% of the cathode production market while it controls all of the anode business.

Raw materials critical to EV battery production also consume a higher proportion of manufacturing costs, Sawmiller says. “As you move this stuff around the world, there’s a lot of places where this supply chain can break or be disrupted.”

Although automakers are working to reduce the amount of rare earth and critical metals used in EVs, the need to tighten the domestic supply chain from mining raw materials to a finished product remains paramount.

Foreign dominance on the supply side in this industry convinced the U.S. Department of Energy in 2018 to award researchers at West Virginia Water Research Institute at West Virginia University a $5 million grant to study more efficient ways to extract rare earth elements and cobalt from the Appalachian region.

The director of the institute, Paul Ziemkiewicz, says researchers have surveyed hundreds of coal mines in Appalachia and some hard rock mines out west that produce acid mine drainage, a byproduct of the mining process. Rare earth elements and cobalt could be extracted from coal mine waste.

“What we found is that acid mine drainage is loaded with rare earth elements,” he says. “We can generate – at least this region and one hard rock mine out west – at least 400 tons per year of rare earth elements. And these are just the mines we know about.” The sites could also produce another 400 tons of cobalt per year, he reports. Cobalt is mined mostly n the Democratic Republic of the Congo, a country the United States has deemed politically unstable.

The West Virginia project has applied for a second DOE grant to study expanding the program on a national scale, Ziemkiewicz says. He acknowledges that 800 tons doesn’t appear to be much. However, the domestic defense industry annually consumes about 800 tons of rare earth materials for its programs. Rare earth elements are also used in electronics, cellphones, medical devices and clean-energy applications such as wind turbines.

The institute, along with the West Virginia Department of Environmental Protection, is spearheading a project to build a pilot acid mine drainage treatment plant near Mount Storm, W.Va., that can separate these elements from contaminated mine water. This process eliminates the need to open a new mining operation, Ziemkiewicz says.

“It’s easily recovered and you don’t need any new permits,” he says. “You’re treating an existing pollutant and you’re recovering value. We think we could go to production very quickly.”

Ziemkiewicz says the amount of rare earth elements is unlikely to reach levels of, say, 16,000 tons annually, but it could help to alleviate some stress on the domestic supply chain.

He says he fields calls from private interests exploring opportunities to the tune of “about one a week,” but cautions that this technology is in its infancy. Yet relying on foreign sources for this material is not an option and the United States needs to act quickly to establish a plan that encourages reliable access to these metals.

“That’s something we absolutely have to do in this country for purely strategic reasons,” he says. “What we want to do is make sure we can do it for good economic reasons as well.”