By Bob Stanger

YOUNGSTOWN, Ohio – For most people, entry into one’s career is through gradual predictable steps, starting with primary and secondary education, followed by years of college oriented toward a specific goal.

Thus we have today’s doctors, lawyers, educators, accountants, clerics and those engaged in specific fields, such as social work and business.

The military might be added to this mix, although those who follow this career path perhaps need more in the line of specific personal qualities than might be required in other fields, such as the ability to fit into a hierarchical regime at the expense of one’s own personality.

(I say this as a somewhat rueful veteran of service in the Navy.)

Then of course there are countless others (including this writer), who entered a career through necessity or default, with perhaps even happenstance added. (Some innate ability along a specific line is certainly a plus in any job choice, however.)

Today, what I receive in retirement income is based almost entirely on years of laboring on what rolls off the presses of daily newspapers that have sadly declined in number in recent years.

I defy anyone in the field of journalism to match in oddity (or even absurdity) just how I happened to pursue what I call my life’s work.

Although my taste for newspaper work was whetted by the year and a half I spent following high school working as a display advertising department copy boy for the Erie Daily Times, my actual start in newspapers took place in, of all places, Tokyo, Japan.

I happened to land a job there doing rewrite work for the Asahi Evening News following an unhappy experience with the Peace Corps in Hilo, Hawaii.

After leaving the latter, and while enjoying the oceanic pleasures of Waikiki Beach on Oahu, I contemplated “what next?” since I had left both the Navy and the Peace Corps behind (as well as a job with the U.S. Commerce Department in Cincinnati) and was, at the same time, reluctant to return to my hometown of Erie with my tail tucked (you know where).

Having served in the Navy in nearby Yokosuka, I knew that there always seemed to be openings for English teachers in Tokyo. So that’s where I headed, booking passage out of Honolulu on one of the American President Line’s white-hulled steamships.

Aboard the ship, I quickly bonded with a fellow Navy veteran, Jerry Stanhoff, who had leads on job prospects in Tokyo including with the Asahi Evening News, an English-language daily newspaper.

But Jerry had his doubts on his ability to work for a newspaper and he suggested that I might apply with the Asahi Evening News.

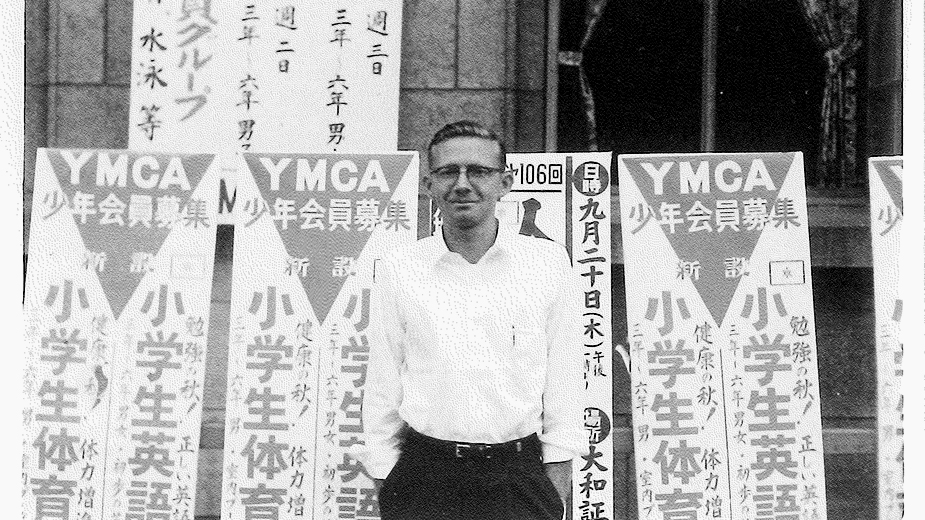

I did this after the steamship landed in Japan. To provide proof of some writing ability, I was asked to write letters to the editor. This I did while seated at a small desk in my tiny seventh-floor YMCA room in Tokyo’s Kanda area, which overlooked squalid Japanese housing built after the incendiary raids by American B-29s in World War II.

In the evening the plaintive calls of cart-pushing noodle vendors rose from byways in the ramshackle housing below.

The Asahi Evening News editor with whom I was in contact, a Mr. Shiba, (whom I believe was a Nisei, an American of Japanese parentage) apparently liked my letters. And, to advance my application further, he asked that I go to a photo studio and send him a likeness of myself, which I did.

(I learned later that Mr. Shiba believed in phrenology … that the shape of one’s head has a strong influence on character. He arrived at this belief, I was told, while working on the crime beat for a Chicago newspaper.)

After passing Mr. Shiba’s letters-to-the-editor and phrenology criteria, I was soon seated at a desk in the sparse offices downtown, which had a dirt floor and were located beneath the tracks of the circular rail line that links Tokyo’s various communities with its central district. (The trains rumbling overhead were a distraction.)

My basic job was to edit articles written by Japanese writers that were to appear in supplements to the newspaper. Some of these articles were fairly well written. Others, however, presented a real editing challenge.

My work was constantly interrupted by the need to edit articles for the daily paper. I also unwisely went on breaks to nearby coffee shops staffed by comely young Japanese girls with a couple of other “foreigners” who worked in the office.

One of these was a guy who had been drafted into the Japanese army. He had been captured by the Russians in Manchuria and had spent time in a POW camp in Siberia.

The office staff also observed an early quitting time, leaving soon after that day’s paper came out. I imprudently followed their example.

These factors put me behind in my editing tasks to the chagrin of Mr. Shiba and others higher up in the newspaper staff who apparently thought that I was just an incorrigible slacker.

The day I was let go, Mr., Shiba graciously took me to one of the coffee shops before letting me know my fate. I was offered a letter of recommendation, which I turned down, and a parting stipend, which I did not turn down.

I remained in Tokyo for some time after losing the Asahi job, conducting classes at a small school in an area known as Ikeburkaro for Japanese who wanted to practice their rudimentary English. Most of these were women of all ages.

But I grew weary of this and decided to return to the United States, booking passage on a ship leaving nearby Yokohama.

Once back in the states, I followed the advice of Jack Sellers, my mentor in Japan with whom I worked at the AEN and lived in the same small apartment complex as I did, and sought an entry-level newspaper job.

An ad in Editor & Publisher led me to travel from Erie to Sandusky on a very cold day in February of 1963.

There, a Scotsman named Tony Thompson, city editor of the paper, asked for proof of writing ability. All I had was a book review from my college days.

“How long did it take you to write this?” Tony inquired.

“Oh, about 45 minutes,” I replied in what was probably a gross understatement.

But the book review was enough to help launch my subsequent newspaper career.

Editor’s Note: Stanger turned 90 earlier this year, and credits his longevity to a healthful lifestyle, including outdoor activities, which have offset the effects of sedentary jobs. He says that no city in his varied past can match Mill Creek Park. He does lament his now age-imposed “slowdown.”

Pictured: Bob Stanger stands in front of the Tokyo YMCA in the early 1960s. The surrounding area was devastated during World War II by American air raids, but the YMCA, a well-built stone structure, survived.