YOUNGSTOWN, Ohio – Martha Bishop, an archives library assistant at the Youngstown Historical Center for Industry and Labor, official name of the Steel Museum, recalls more than a decade ago a man walked into the library requesting drawings of the former Brier Hill Works of the Youngstown Sheet & Tube Co.

It wasn’t an unusual request. Often, architects, engineers and contractors use the archives to examine blueprints related to old industrial buildings or machinery. What Bishop didn’t know was that the visitor needed the information as a starting point for what would become a $1 billion expansion of Vallourec’s pipe and tube operation just off Martin Luther King Jr. Boulevard.

“Connecting the dots in retrospect, it turns out it was the section of Brier Hill where they expanded,” Bishop says. “Early on, they were clearing the section and wanted to know what was here before. They were interested in what they were finding in the ground.”

The Historical Center for Industry and Labor has for 30 years helped to tell the story of the Mahoning Valley through the eyes and experiences of industrialists, workers, managers, and others engaged in occupations that helped to build this community.

Thousands of artifacts, documents, and pieces of artwork, photographs and manuscripts are on permanent public display at the center – a physical reminder of how men and women lived and worked in the Valley’s industrial economy of the 20th century. It also serves as a repository for additional documents, books, trade journals, posters and other important archival materiel related mostly to the local iron and steel industry.

But more so, the center has evolved into an educational laboratory for students and the community, says its site manager, Marcelle Wilson. “It started out as primarily an archives library and a museum,” she says.

But since it opened in 1992, the historical center has served a much broader purpose. Here, students enrolled in both graduate and undergraduate programs have an opportunity to gain practical, hands-on experience in applied history, she says.

“They get the opportunity to work in a museum,” Wilson says. “It’s a hands-on, day-to-day realistic opportunity to discover what it’s like to work here.”

Alexys Diamond, a student in the history program at Youngstown State University, is among several who have secured internships at the museum over the summer. “I’ll be working with archives, catalogs [and assigned other duties],” she says. “I’m going through the history program and have a minor in applied history.”

Wilson says other universities have sought out the center’s program for internship opportunities. This year, for example, a student from the University of Akron and another from the University of Illinois – Springfield will join the team.

That other universities seek out the Youngstown center underscores its importance and the role it plays in the community and beyond, Wilson says. “It’s exciting,” she says. “We’re being introduced to their program and they to ours.”

Travelers, academics, media, authors, family members and others from all over the world have visited the center to examine how 20th century industry shaped the region, Bishop says. An immigrant workforce, technical innovation, efficient production methods – all contributed to the legacy of the Mahoning Valley as a global manufacturing powerhouse.

“It’s amazing how much the Youngstown mills were mentioned in national journals,” Bishop says. “Markets were global – these companies had sales offices overseas and clients in Asia, South America and Europe. Globalization wasn’t just a buzzword. It was their business.”

Bishop, who has served in the archives and library for more than 20 years, says the center has attracted scholars from throughout the world who are also interested in the de-industrialization of cities such as Youngstown and how the community responded. “There are numerous visitors that find us on their own,” she says. “Many in the museum field note that this there’s no other place like it in the country.”

She credits the vision and persistence of the late state Sen. Harry Meshel, who represented this district in the Ohio General Assembly between 1971 and 1993 and witnessed firsthand the retrenchment of the steel industry across the Mahoning Valley. As majority leader of the Ohio Senate between 1983 and 1984, Meshel used his clout to appropriate the necessary funding that provided the foundation for the historical center.

“It was his vision to preserve the story of how this industry led to the growth of this community and the whole Valley,” Bishop says.

Just as evocative is the building’s design and architecture. Michael Graves, regarded as among the most prominent architects of the latter half of the 20th century, used a postmodern design that incorporates the look of steel mills from different eras, including a smokestack-like addition to the building.

Like the steel industry, however, the center had its share of challenges. During the Great Recession, the Ohio Historical Society – today, the Ohio History Connection – had contemplated shutting the museum down, at least temporarily. Swift action by YSU, its history department and the state kept it open. A management agreement was signed in 2010 where the history department would manage daily operations.

Local management has led to exhibits that better reflect the cultural and industrial heritage of the Valley, Wilson says. In addition to its permanent collection, the center has public displays that feature the William B. Pollock Co., Vallourec, and the Youngstown General Duty Nurses Association.

Past exhibits include the Little Steel Strike of 1937, which turned deadly in Youngstown. The exhibit earned the Ohio Academy of History Public History Award in 2014.

Among the permanent exhibits at the site are a mock kitchen from a company house, items a steelworker would store in a locker representing different decades, a washbasin from U.S. Steel Corp.’s McDonald Works, and videos of steelmaking and the demise of the industry.

“It’s the story of the grit and integrity of these men and some women,” Wilson says. “They had to work very difficult jobs that were very dangerous to provide for their families.”

Wilson has expanded the reach of the center to encompass those in skilled nursing or assisted living centers who require memory care. These programs include modified tours, bringing artifacts to these complexes to help spark residents’ memories, or simple PowerPoint presentations that encourage interaction with residents. “It’s fun,” she says.

And, to commemorate its 30th anniversary, the museum has launched a series of lectures that kicked off in May. These lectures feature Mahoning Valley Historical Society Executive Director Bill Lawson, YSU history professor emeritus Tom Leary, former YSU history professor and Youngstown Historical Center site director Donna DeBlasio, and representatives of OCCHA, a social services organization representing the Hispanic community that will discuss migration from Puerto Rico to the Youngstown area.

While the center celebrates the rich history of the Mahoning Valley, it also embraces its role as a pathway for the future of the community and how it interacts with other disciplines such as math, geology, science, technology and engineering.

The center is working with the Center of Excellence, a partnership between YSU and Eastern Gateway Community College, to prepare an exhibit set to be unveiled in September, says assistant curator John Liana.

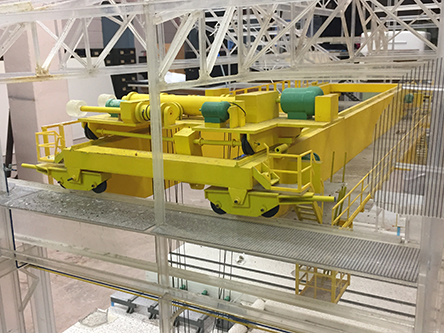

The project constitutes refurbishing a model of a continuous caster, equipment used to cast molten steel into strips or shapes. The model, donated by Cleveland Cliffs to the Ohio Historical Society during the 1970s, has been stored in the basement of the center nearly 30 years.

“We’re bringing in engineering students and faculty from Eastern Gateway and the Center for Excellence to help with the project,” he says.

The sprawling plastic model has moveable parts and most certainly has pieces missing that will need to be replaced, Liana says. It’s possible that these students could use 3D printing technology to reverse engineer and manufacture the plastic components through additive manufacturing.

“We’re going to move the model from where it sits to another location downstairs and build a room around it,” Liana says.

Bishop says it’s a great opportunity for future engineers and those engaged in STEM programs: “It’s a great experience for students working in some kind of engineering.”

Ultimately, the Youngstown Historical Center for Industry and Labor represents a full snapshot of the heritage of a community and its potential, Wilson says.

“We want to tell a multifaceted story that involves not just the leaders, owners and managers, but also the daily workers,” she says. “What they did on a daily basis, how hard did they work, how did they do their job, what dangers did they face?”

Pictured at top: Marcelle Wilson and Martha Bishop peruse a Vindicator front-page story about the U.S. Supreme Court decision in the landmark case Youngstown Sheet & Tube v. Sawyer.