YOUNGSTOWN, Ohio – Kimberly Smith was always interested in the nursing profession. But a love for animals led her to pursue a career as a registered veterinary technician.

Now, 30 years later, Smith finds herself doing things a typical RN would do and then some.

“We are radiology techs, anesthesia techs, dental technicians,” Smith says. “We also can give vaccinations and do routine physical exams.”

Smith works with a team of vet techs and veterinarians at Angels for Animals in Canfield. Since its incorporation in 1990, the nonprofit has provided veterinary services, cat and dog adoptions and shelter medicine services for Mahoning Valley residents and communities.

As need has grown, so has the organization. Fundraising efforts since 2015 culminated in the construction of the Angel Wing – a $10 million veterinary hospital at 4750 W. South Range Road in Canfield. The organization moved into the hospital in May 2020, says founder Diane Less, and provides veterinary services as well as a few niche businesses, including pet euthanasia.

“If you’d have said to me 32 years ago, ‘You’re going to be running a big animal shelter,’ I would have said no. That won’t happen,” says Less, who was operating her own art studio when Angels was founded. “But I always loved animals.”

Since the founding of the nonprofit, Less has seen the need for shelter medicine increase. On a given day, Angels for Animals veterinarians can perform 30 to 60 spay/neuter surgeries alone, she says.

The volume of work requires the clinic to maintain sufficient staff. That includes vet techs, for which she says there is a huge demand.

“I can almost find veterinarians easier than I can vet techs, which is hard to believe,” Less says. “We have probably five vet-tech programs within 100 miles of this place. We don’t get any.”

To help bridge the gap, Angels has partnered with the Youngstown campus of Eastern Gateway Community College for its veterinary technician program. Classroom education takes place at the college and Angels provides students the necessary clinical experiences.

In the first class of the program, 22 students completed their admission requirements this fall and will begin the clinical portion in the spring. The first class is expected to graduate in fall 2023.

Admission requirements are robust. To be accepted, students must pass courses in math, English and chemistry, and attain at least 40 hours of field experience with a private practice, shelter or farm, says Dr. Mike Sabihi.

“Anywhere they can deal with working with animals, dealing with animals and getting hands on,” he says.

High school graduates with a grade of C or better in math and chemistry can transfer those credits to EGCC.

The two-year vet tech program requires 64 credit hours students must complete to graduate, of which 80% to 90% will be at Angels for Animals, Sabihi says. While a vet tech isn’t responsible for everything a veterinarian does, it’s two years of school compared to eight.

“One of the toughest schools to get in are the veterinary schools,” he says. “You’ve got to have a good GPA. You’ve got to have a lot of field experience.”

Along with requiring less schooling, the need for vet techs makes the job search less competitive. Within two to five years, the demand for vet techs will increase 20%, according to Sabihi. In Ohio and other parts of the eastern United States, salaries can range from $30,000 to $40,000 and more, he says.

“A lot of places are looking for them,” he says. “Before they graduate, they’ve already got the job.”

Kelly Lesnak has been a veterinary technician for a little more than a year. Originally, she wanted to be a vet. But after three years at Westminster College, she transferred to the Vet Tech Institute in Pittsburgh and earned her degree. Today, she’s the head registered vet tech at Angels for Animals.

Lesnak works primarily in the surgical prep area and administers control drugs and intubation for the patients. She also monitors anesthesia and administers reversal drugs for the animals coming out of surgery.

The daily work can be a lot for some people unused to it, she says. But vet techs become accustomed to the work. Those who love it are successful, she says.

Although she wanted to be a vet, Lesnak says she has no plans to pursue that career at this point.

“I like where I am right now,” she says. “I like being in charge of surgery. I don’t necessarily like doing the surgeries itself.”

Shelter medicine is “a completely different environment” from private practice, she continues. The surgery is faster paced and every day is different. Lesnak says she’s always had a soft spot for stray animals. So working at Angels gives her the opportunity to care for that population.

“You get to help the animals that aren’t being given everything they need,” she says. “It’s nice to see them come in and then get everything they need and go out and get a home.”

Being a vet tech provides job flexibility that veterinarians don’t necessarily have, says Amber Padula, a vet tech with Angels for Animals and the EGCC program. Padula has been a registered vet tech, or RVT, since 2004.

“You can change your career path in a lot of ways,” she says. “If you decide being more hands-on with the animals isn’t as much for you, you can also look into doing research. There’s a lot of facilities for that.”

Vet techs can work in pharmaceutical sales and medical equipment sales, as well as lab work, she adds. Others have gone on to work in pet insurance.

“And since they are in demand so much – really anywhere in the state you can walk in with an RVT license and you could get a job,” she says.

Vet techs can expect to put in long hours, which can be emotionally draining for some, particularly with regard to euthanasia, Padula says. It’s important that vets and vet techs understand what that entails before getting into the profession – not just the mechanics of it, but also dealing with grieving families.

“There’s happy puppy visits and happy kitten visits,” Smith says. “But there’s also the opposite end. The end of life. And that happens every day.”

Daily tasks for vet techs include analyses of urine, fecal and blood samples, Padula says. They’ll also need to be familiar with lab equipment and know how to read an electrocardiogram, monitor oxygen percentages and measure blood pressure, she says. That’s particularly important when assisting veterinarians during surgery.

“You have to be someone who can be an advocate for all of the patients,” Padula says. “Doctors are busy. They count on you for their support.”

While veterinarians make many of the final decisions in the treatment of a pet, they work closely with vet techs throughout the day, says Dr. Jennifer Clipse. Vet techs help the vets to perform necessary tasks, whether it’s holding the pets during certain treatments or monitoring the pet during surgery.

“It’s definitely a group effort,” Clipse says.

Clipse has worked as a veterinarian since 2016, both at Angels for Animals as well as in private practice. From the time she was a little girl, Clipse was interested in science and wanted to be a vet, she says. Initially interested in marine biology, she found she enjoyed all aspects of veterinary medicine, so pursued general practice.

“I like that I see new things every day,” Clipse says. “It’s always a learning experience.”

For students who want to explore careers in veterinary medicine, Clipse recommends contacting Angels for Animals at 330 549 1111 for opportunities to shadow. Students typically start on the shelter side learning the ins and outs of shelter medicine and becoming acclimated with the animals. Then they’ll be moved to the wellness side where they can interact with the vets and vet techs.

“Occasionally, depending on their comfort level, they may be able to see a surgery or two in a day,” Clipse says.

While they’re in school, Clipse advises students to focus on the sciences, particularly biology and chemistry, as well as math. Some vets will use geometry to plan their surgeries, she says. If they plan to open their own clinic, “Business classes are a must,” she adds.

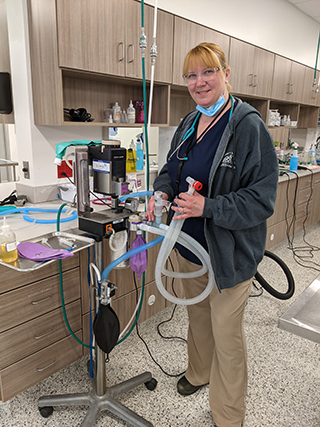

Pictured: Kelly Lesnak (left), head vet tech, works with her team to prep a patient.