When English Isn’t a Child’s First Language

YOUNGSTOWN, Ohio — After leaving Puerto Rico in the wake of Hurricane Maria in 2017, Moises Diaz and his family faced a new challenge: acclimating themselves to a new home and culture in Campbell.

Integrating his five children into Campbell City School District came with its own set of challenges, not the least of which being the language barrier. Cultural differences, understanding how the school system worked, the weather and even the food took some getting used to.

“In Puerto Rico, they serve you rice and beans and meat every day in the school,” he says.

Students who don’t speak English as their first language are enrolled in the district’s English learner program and tested to gauge their comprehension. This determines what type of help they receive in the classroom. The system helped the Diaz children a lot, he says.

“Every year, they test the kids again,” Diaz says. “After three years, three of my kids tested out of the English test. So they don’t need the assistance right now.”

Today, his children – starting grades 11, nine, seven, five and three, respectively – are doing well integrating into their classes and are playing on the school’s soccer and volleyball teams.

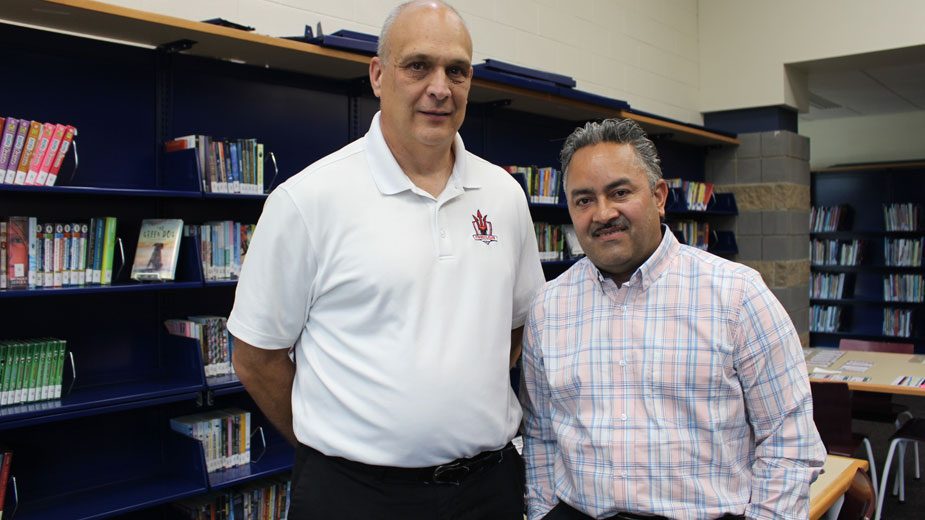

Diaz got involved with the schools as well, first as an in-class assistant working with Spanish-speaking students, last year as family/community outreach coordinator for the district. His job is to bridge the communications gap between the school and the families whose first language is Spanish.

“Some parents stay away because they don’t understand the language,” he says. “But I think the school is doing a great job reaching out to them and letting them know, ‘We can listen to you. We can talk to you. We can communicate.’ ”

By relating to families through shared experience, he’s able to improve communications between parents and the school, as well as establish mutual trust.

This makes it easier to connect with students and to help them through any trauma they may be dealing with, he says. When living through a hurricane, “you’re worried about your life that day.” After that, there is no school, as well as no electricity or running water.

“So then you move to another country, and you have to say bye to grandpa, grandma, your friends, your bicycle, leave your toys and move,” he says. “And then you have to face another language.”

Social and emotional learning strategies help students to cope with “those situations where they have to leave because of a traumatic situation in different areas of their life,” Diaz says.

Diaz also works to provide clarity on cultural differences. For instance, students in Puerto Rico spend much of the school day outside. So if there is a lot of rain, “they won’t go,” Diaz says. The district noticed Hispanic families weren’t sending their children to school during inclement weather.

Additionally, it’s common for schools in Puerto Rico to close the day after a major sports victory, such as a Puerto Rican boxer winning a championship match or for holidays and family celebrations, including birthdays. Part of Diaz’s job is explaining to parents the importance of attendance in mainland schools.

“We explain to them the way the school functions,” he says. “I think we’re doing a good job. They realize the schooling here won’t stop.”

The district has adapted to and learned from the culture, says Jim Klingensmith, principal of the Campbell Elementary & Middle School K-6 building. For instance, because many Hispanic families celebrate Three Kings Day, the district extended its holiday break to Jan. 6.

“We knew we were going to lose a lot of kids that day. So we built that into our waiver days,” Klingensmith says.

Incorporating Hispanic culture into the fabric of the community is important, Klingensmith says, because “it shows the students and even the parents that we’re trying.”

The district offers Spanish classes for teachers and staff to learn basic vocabulary and gestures to help make the Spanish-speaking students feel more comfortable. And the efforts are paying off, he says.

“You see the kids smile. They’ll say something to you and you’ll reply back … and they’re like, ‘Oh, he’s trying. He’s not right. But he’s trying,’ ” Klingensmith says with a laugh. “It puts their guard down and it opens up communication and you get more accomplished that way.”

Having a point of contact to field calls and actively reach out to parents makes them more engaged with their children’s education. So they call the school more often to ask questions, the principal notes.

The COVID-19 pandemic created a host of new challenges, Diaz adds. Hispanic families “take the news really serious,” and have opted for remote learning.

Diaz helps them understand how to operate the Chromebooks and access their school’s online assets.

And because the pandemic disproportionately affects Hispanic and Black communities, those families are more likely to have lost someone to the virus, he says.

Diaz has spoken with several families in the community who have lost relatives in other states and in Puerto Rico, who hesitate to send their children to school.

“If they say in the news that school is not good for kids, they don’t send them,” Diaz says. “I think we have a lot of Spanish-speaking kids home right now because of that.”

About 15% of the students in the K-6 building alone are English learner students, Klingensmith says. Overall, just north of 30% of the district’s students are Hispanic. And the numbers are increasing.

The local trend mirrors a national surge in English learner students. In the 2016-17 school year, the number of English learners in the United States increased by 28.1% from the 2000-01 school year, according to data from the U.S. Department of Education. In that time, Ohio saw its English learner population increase by a range of 100% to 199.9%, according to the report.

The Youngstown City School District has about 440 English learner students, most of whom speak Spanish as their first language, reports Ava Yeager, the district’s chief of school improvement. That’s up from 289 four years ago. Those students currently account for about 7% of the district’s total student population.

“We’re looking at an increase of about 25 students per year,” Yeager says. “So we do definitely know that the area is increasing with more students that need English language services.”

As more families move to the area, it’s common for their relatives to follow, school administrators say. Outreach efforts are vital to ensuring the students and families are integrated into the school system.

Youngstown City’s English learner program staff distribute language usage surveys to new families to evaluate a student’s ability to comprehend English, says Dennis Yommer, program coordinator. From there, staff get permission to screen students for the language services they may need.

“Should a need be identified, then what we do is we begin to provide services for that student,” Yommer says. Communications are sent home in a family’s native language, including robocalls and letters.

“We do our best to keep them in the loop, just like any other family that’s in the district,” he says.

To keep them on track with the rest of their class, students in each district’s English learner program receive in-class help from bilingual educational assistants on core content, including math, science, history and English language arts, or ELA.

TESOL teachers (Teaches English to Speakers of Other Languages) foster the students’ skills in English, Yommer says. This year, the Youngstown district hired four TESOL teachers, bringing its total to 15. It has room for one more.

“Ultimately, our goal is to reduce that scaffold in their first language and build up their second language,” he says. “So hopefully over time, that shift from the educational assistant to an [English language] teacher moves a little bit.”

TESOL teachers work to develop comprehension in four areas: listening, speaking, writing and reading. The district has found that students tend to pick up verbal communication faster than writing.

“After a year of being in an American school, they’ll have listening and speaking down pretty well,” he says. “Writing sometimes tends to be the hardest to move them.”

Once a student is proficient in English, “It’s often shown that those students, those scholars, actually outperform [other] students in the room,” Yommer says.

“This curriculum is unique in a sense that it addresses a student’s language capabilities,” he says. “So no longer are we looking at the standard applied for their grade level. We’re taking a look at that individual student’s language level.”

Bilingual staff members in Youngstown City’s Parent Pathways office provide a point of contact for parents who have questions. This year, the district looks to hire two more Parent Pathways staff members.

The office also works to engage Hispanic families in school activities, particularly parent teacher conferences and community events, Yommer says. Each year during Hispanic Heritage Month, the schools invite students and parents into the buildings to meet the teachers, administrators and “to see what their children are doing day in and day out, and who they’re working with,” he says.

Building that trust between families “helps with the community piece” as well, says Campbell’s Klingensmith, because it encourages the students to live and work in the community when they get older.

“We’ve made huge strides in this area in the last couple of years,” he says. “We’re not where we need to be yet. By all means, we’re still growing in this area. But we’ve made huge leaps and bounds and the kids seem happy.”

Copyright 2024 The Business Journal, Youngstown, Ohio.