Flashback: ‘My Life as Mayor Would Be a Torture’

YOUNGSTOWN, Ohio – During the early 1930s, shortly after serving his one and only term as mayor of Youngstown, Judge Joseph L. Heffernan was asked by The Saturday Evening Post to write a firsthand account of how politics operated in the city – at the time one of the busiest industrial centers in the country with a population of more than 170,000.

There was just one problem. Heffernan found that his story would impugn the reputations of those who were still alive and also still very influential in municipal, Mahoning County and state politics. His solution was to change the names of the actors in the story, but not the story itself.

But it became clear to Heffernan that even assigning pseudonyms couldn’t conceal the identities of those involved. After starting to write a draft of his account, he shelved the project.

That unpublished manuscript survives today in the archives and special collections division at Youngstown State University’s Maag Library.

“I went into office a poor man. I left office a poor man,” reflected Heffernan in his 21-page memoir. “I passed up hundreds of thousands of dollars simply because I wanted to go straight. Because of my attitude toward public office, efforts were made to frame me. There were persistent plans to drive me from the City Hall, and I even had the interesting experience of dodging charming women who were supposed to vamp me.”

Such was Heffernan’s indoctrination to the mean streets of Youngstown politics in an era consumed with bootleggers, bribery and menacing political bosses who were queasy to the very concept of change. In Heffernan’s eyes, this was no place for a man of integrity.

“When you read of the struggles and torture I underwent, perhaps you will wonder if people can really be vicious enough to do the things I experienced, or if there is any hope at all for honesty in municipal government in its present form,” he would write.

Heffernan was hardly naïve – far from it. By the time he had returned to Youngstown in 1920 to seek political office at age 33, he had already lived a life packed with travel and adventure. He’d quit school to go to work, but returned to complete his high school degree. He studied at Ohio State University and Valparaiso University, worked in steel mills in the Mahoning Valley, was employed on a steam shovel gang in the Midwest, earned a living as a chef in Illinois and as a cook on a steamboat along the Ohio River, fished for pearls along the Wabash River, became a rivet heater on oil rigs in Oklahoma, tried his hand at prospecting in Death Valley, and helped build aqueducts in the Mojave Desert.

In 1910, he returned to Youngstown to embark on a career in journalism and worked at the Youngstown Telegram, The Vindicator, and the Ohio State Journal in Columbus before heading off to Europe to freelance from Paris and London. He returned to Ohio when World War I broke out in 1914, passed the bar exam in 1916, and became an attorney. In 1917, after the United States entered the conflict, he made his way back to Europe as a war correspondent for Stars and Stripes. He arrived back in Youngstown with a desire to hold elective office.

Heffernan was ambitious, young and connected to the right people inside the Democratic Party. Among his friends was Vic Donahey, who was elected Ohio governor in 1922. Another political mentor was Newton D. Baker, the Cleveland attorney and prominent figure in the Democratic Party who served as Woodrow Wilson’s secretary of war.

Yet Heffernan was also well liked among the city’s working class. “I suppose it was only natural that on taking up law, I was interested in politics,” he wrote. “Fortunately, I was well known by the working people of this city.”

A growing law practice, plus the desire to engage in politics, convinced Heffernan to jump into the race for Democratic Party committeeman in 1922, defying the party establishment. Even more surprising to the party elders was Heffernan’s successful bid for Mahoning Democratic Party chairman that same year.

None of this went over well with Edmond H. Moore, a former Youngstown mayor, brilliant attorney and living legend in local politics, who served as Gov. James Cox’s campaign manager during his presidential bid in 1920.

Heffernan refers to Moore as “Boss Tom Curtin” throughout his abandoned account. A note handwritten by Heffernan shortly before his death in the late 1970s discloses all of the identities of the players in the manuscript. Donahey, for example, is Bob Jackson, while Baker’s name is changed to Douglas Henderson in his story.

With advice from Baker, Heffernan organized a Young Democratic Club that eventually brought in a coalition of young and older members who were irritated at Moore’s overbearing control of local politics. According to an interview conducted in 1974 by former YSU history professor Hugh Earnhart for the department’s oral history program, Heffernan recalled that Baker described Moore as “an old wolf. He wants to keep power himself, and does not enjoy seeing young men getting ahead.”

As such, “I was to be stopped before I started,” Heffernan reflected in his memoir, as Moore and his “henchmen had no welcome for me.” Despite Moore’s repeated attempts to derail the young attorney’s efforts, Heffernan’s coalition prevailed and successfully outflanked Moore’s machine. An arranged dinner to establish a truce between the two men ended with Moore growling to a friend, “The young rascal has licked me. But he’s right, I am about through.” Moore relocated to Cleveland and joined a prominent law firm.

By 1923, Heffernan’s stature had grown. He was appointed by Donahey to fill a vacant spot on the municipal court, a seat he would win in his own right later that year.

While on the bench, Heffernan earned a reputation for fairness, but could also be unorthodox. According to Heffernan’s oral history at YSU, on one occasion he selected a young man, John Davis, out of a group of accused before the court and appointed him judge for a day. “Judge Davis did an excellent job,” Heffernan recalled. When he asked Davis to adjourn the court, the prisoner reminded Heffernan that he had not tried his case yet.

“Oh, that’s right,” Heffernan said. “I think you should try yourself.” Davis recommended a $5 fine for drunkenness and three days in jail – suspended. Heffernan agreed.

In 1927, Heffernan launched his campaign for mayor of Youngstown. It was during this campaign that the judge met John Farrell, an able, wealthy, political organizer who was referred by friends and who threw his support behind the judge.

“During the campaign, I had no reason to be apprehensive as to the future,” Heffernan wrote. “Soon, however, I was to discover that my life as mayor would be a torture such as I had never foreseen. My disillusionment began as soon as I took office.”

It started almost immediately with Farrell, whom Heffernan refers to in his account as Egan Drew. According to Heffernan, Farrell all the while had designs on running local government as a protection racket, arguing that it was his influence that put Heffernan in office in the first place. It was clear to Heffernan that Farrell was maneuvering to fill the shoes that Moore had left empty, and the judge would be a “willing puppet.”

Instead, Heffernan rebuffed repeated attempts by Farrell to use him as a conduit for graft. “Don’t be a damned fool,” Heffernan recalled Farrell telling him. “You will go out of office broke and everyone will laugh at you. I could make a fortune for you. You’d be set for life.”

In the end, Heffernan’s reasoning was simple. “I could not bring myself to be a crook,” he would write.

Still, the battle with Farrell intensified. A heated exchange ended with Farrell threatening, “I’ll drive you out of office. I’ll crush you in the gutter,” Heffernan wrote.

Heffernan would reflect that he sought public office for the sole purpose of providing better, efficient government for the people. Graft and corruption didn’t align with his idealism, which by now was shattered. As Heffernan writes: “Alone I sat with my bitter thoughts, wondering at the difference between my dream of the mayor’s office and the sordid reality. I even thought of resigning. Politics was not worth such mental anguish.”

Heffernan didn’t quit, and neither did Farrell. At one point, the political operative told the mayor that he was jockeying for statewide power and that if Heffernan played his cards right, he could be elected governor. “He could guarantee us at least $100,000 a year. All I had to do was let him run things, keep quiet, and take my cut,” Heffernan recalled. Then, Farrell produced $500 and shoved it in the mayor’s pocket as a set-up. Heffernan returned the money that night, and war was officially declared.

According to Heffernan’s account, Farrell and others orchestrated an elaborate smear campaign. One of the schemes involved setting him up with women. On one occasion, Heffernan was suspicious of a young, beautiful woman who maneuvered past his secretary, using a fake referral to get by, and entered his office.

“She suggested that I meet her outside at an agreed rendezvous,” Heffernan writes. At that moment, the mayor’s foot pressed a floor button beneath his desk, and then his secretary bolted in with a stack of documents. He apologized to his guest, noting that he was obliged to finish the work today. Once the woman left, Heffernan turned to his assistant: “If there’s nothing important on the docket, I’m going home. It’s been a tough day.”

Heffernan’s tenure as mayor – he did not seek re-election because of charter limitations – emerged as an overall success, despite political opposition from groups such as the Ku Klux Klan and chicanery such as Farrell’s. When he left office, the city was on sound financial footing, while Heffernan was also successful in establishing relationships with immigrant groups from eastern and southern Europe.

Once out of office, Heffernan again turned to practicing law, but many of his progressive ideals still persisted. It was Heffernan, for example, who organized a Youngstown chapter of World War I veterans to march on Washington in the summer of 1932 during the throes of the Great Depression as part of the Bonus Expeditionary Force, or Bonus Army.

Veterans, demanding Congress pass a bill that would allow them to cash in early bonus certificates they earned during the war (the bonuses were not scheduled to mature until 1945), mobilized a march on Washington that numbered at one time about 15,000 strong. Roughly 100 of those marchers were from the Mahoning Valley and organized by Heffernan.

Once in D.C., Heffernan founded the B.E.F. News, the official publication of the Bonus Army.

About 10,000 marchers set up a tent city along the Anacostia Flats and on July 28, 1932, U.S. armed forces under the command of Gen. Douglas MacArthur, launched an attack on the site in order to disperse the marchers. The entire camp went up in flames, injuring hundreds of servicemen, their wives and children.

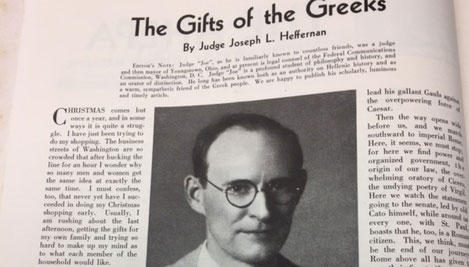

Heffernan continued to be active in Democratic politics, leading to appointments as counsel to the Federal Communications Commission in 1934 and as an assistant attorney general for Ohio in 1937. He was also active in writing scholarly articles for magazines – especially ones devoted to the history of Ancient Greece.

“I’m now hoping to finish a history which, I’m sure, will displace Gibbon’s ‘Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire,’ ” he joked to YSU’s Earnhart more than 40 years ago.

He never again held elective office and retired to live with his daughter in Maryland, where he died in 1977 while working on a book about the settlement of the Northwest Territory.

Pictured: In 1930, when Joseph L. Heffernan was mayor, corruption did not align with his idealism. “I even thought of resigning. Politics was not worth such mental anguish,” he later wrote.

This Flashback story is the second of a two-part series. The first, “Flashback to an Extraordinary Life Well Lived,” can be found here

Copyright 2024 The Business Journal, Youngstown, Ohio.