Framing History Is Butler’s Art

YOUNGSTOWN, Ohio — There is a nondescript painting by Nehemiah Partridge you see as you enter the front entrance of the Bacon Gallery of The Butler Institute of American Art. The subject – a young girl named Catherine Ten Broeck – is dressed in a dark-brown gown holding a rose in her right hand and a small bird perched on her left.

The piece dates to 1719 – the artist found it important to place the year in the far right-hand corner. Painted 300 years ago, it is the oldest work in The Butler collection, and it was presented to The Butler by Josephine Butler Ford Agler, granddaughter of museum founder Joseph G. Butler Jr.

It’s not the most striking painting by far. Still, the image is an expression of early 18th-century American art – nothing elaborate, just plain, the work of a journeyman – but one reflective of an emerging “middling sort” people then subjects of a larger colonial empire.

“These were primitive paintings painted by itinerant craftspeople,” says Louis Zona, director of The Butler. “That’s where it was in the 1700s.”

And that is what makes The Butler such an important asset in the course and scope of American art and American history. The Butler tells the story of a country through tangible artistic interpretation that predates the founding of this nation to its most modern forms of expression.

“This is art created by Americans,” Zona emphasizes.

“America is a melting pot of different cultures and every culture has added something to this,” he says.

As America changed, so too did its art.

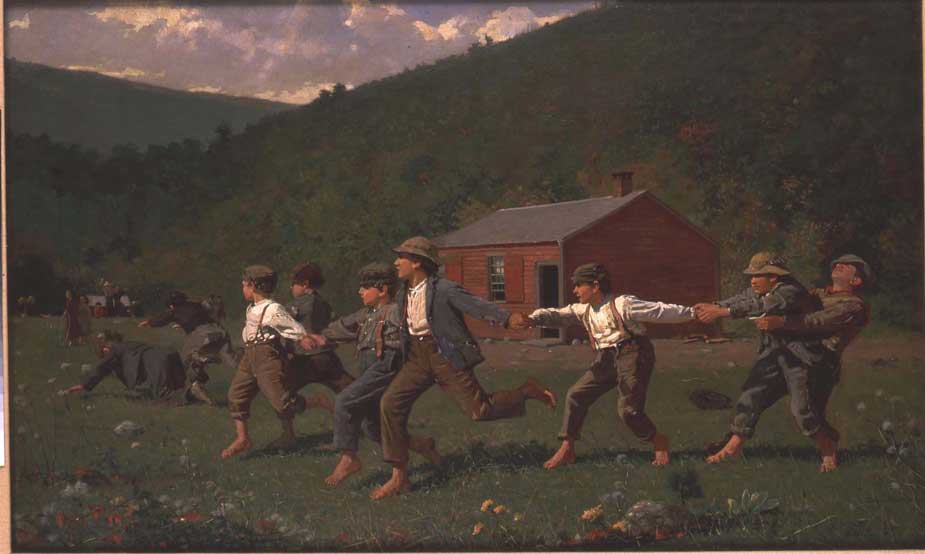

Masterpieces of the 19th century such as Winslow Homer’s “Snap the Whip” evoke the simplicity of a children’s game outside of a one-room schoolhouse. Albert Bierstadt’s romantic homage to the West in “The Oregon Trail” is a beautiful, panoramic landscape painted in 1869 that exaggerates the vastness of this part of the country as German immigrants make their way through a mountain pass.

The list of other works and artists is just as remarkable and marks significant milestones throughout history. Mary Cassatt’s pastel, “Agatha and Her Child,” represents a breakthrough moment for American women artists during the late 19th century, while more contemporary examples such as Georgia O’Keefe’s “Cottonwood III” from 1944 is a major statement in that artist’s evolution, Zona says

E.A. Burbank’s portraits of Native Americans – two of them of the Apache chief Geronimo and one of Geronimo’s daughter, E-wa, all painted from life – are on display in the Western collection of the museum. There is also a dose of realism in William Gropper’s “Youngstown Strike,” a 1937 painting that depicts a violent clash during the 1916 strike at the Youngstown Sheet & Tube Co. The piece was most likely inspired by the “Little Steel” strike of 1937, which affected Sheet & Tube.

Romare Bearden’s 1970 collage, “Hometime,” serves as an example of important African-American works, while other 20th-century artists in the collection – Jackson Pollock, Edward Hopper, George Bellows, Clyde Singer, Andrew Wyeth, Andy Warhol, Norman Rockwell – exemplify a variety of styles and originality that helped cement the United States as the center of the art world in the years following World War II.

“I would like to think we’ve made a significant contribution – historically and with contemporary art,” Zona says. He recalls the remarks of an influential art dealer, Ivan Karp, who was an early aficionado of the pop art movement of the 1960s and was in part responsible for developing a gallery in the Soho district of Manhattan.

“He said to me one day that a visit to The Butler for the art connoisseur is akin to a visit to Mecca,” Zona says. “I’ve never forgotten that.”

As The Butler celebrates its centennial this year, Zona marvels how American art has matured from its colonial origins to become the center of the international art world. “If you’re an artist – French, Italian, German – and you want to make it in the world, you come to New York,” Zona says. “It’s a position we haven’t relinquished.”

The museum founder and its namesake, Joseph Green Butler Jr., understood this before anyone else, Zona says. Like many of his contemporaries, the Youngstown industrialist during the turn of the 20th century collected his share of paintings from Europe. Unlike his colleagues, Butler had an eye for American artists that few others shared.

Then, in 1917, a fire swept through Butler’s Wick Avenue home, destroying much of his collection, Zona says. “He vowed to build another collection – this one all American.”

Butler engaged one of the most celebrated architectural firms of the era – McKim, Mead & White, which had recently finished renovations to the White House for President Theodore Roosevelt. The idea was to build a museum dedicated solely to the display and preservation of American art. The new museum was officially dedicated in 1919.

“He was very proud of what he accomplished here,” Zona says. Butler believed that as a center of industry, Youngstown should also become a cultural fulcrum that would draw national and international attention: “The idea of a museum dedicated to American art was a novel idea.”

The centerpiece of the collection, indeed, the soul of The Butler, is Homer’s “Snap The Whip,” Zona says, which Butler acquired after the assassination of his good friend, President William McKinley. “He searched for that painting, found it, and spent an enormous amount of money to acquire it,” Zona says. The industrialist spent an estimated $5,000 on the piece, a substantial sum at the turn of the 20th century.

Yet for a long period of time, the piece was hidden from public view, Zona notes. Butler’s grandson, Joseph Butler III, realized that the cost to insure the painting would be so exorbitant that it would cripple the museum budget. “It remained in his office. And for those who wanted to see it, we’d have to be taken into Mr. Butler’s office,” he says.

Zona started working for Joe Butler III after he finished his doctoral work. “He was a very good man. He wasn’t educated in art, but he had a wonderful eye.”

The original collection consisted of about 30 pieces, Zona says. Today, the holdings exceed 22,000 individual works by thousands of American artists.

Among the pieces Butler III acquired were John Singer Sargent’s “Mrs. Knowles and Her Children,” Robert Vonnoh’s “In Flanders Field” and Bierstadt’s “The Oregon Trail.” His father, Henry Butler, was responsible for The Butler’s marine collection, such as Fitz Henry Lane’s “Starlight in Fog,” painted in 1860.

“If you are going to study American art, if you want to appreciate the beauty of American art as a reflection of American history and culture, then you have to go to The Butler,” says David Shirey, a former art critic for The New York Times and Newsweek.

Shirey, a Mahoning Valley native, lives in New York City today and says that any major show that features American art in that city is incomplete without a piece from the Butler. “I went to an exhibit at the Whitney [Museum of American Art] that featured a show devoted to Grant Wood,” Shirey says. “There was a piece there from The Butler.”

Shirey notes that he’s had a long association with The Butler – he gave the keynote address during its 50th anniversary – and says the collection is of international significance. “When Joe Butler amassed his collection, the ascendant taste in art was toward abstraction,” he says. “He was capable of seeing the inherent value of representational art and recognizable imagery.”

“Snap The Whip” is one of three such similar versions painted by Homer and is considered the most esteemed by many critics, Shirey says. Representation by the Hudson River School is also prominent in the collection, he says.

Zona has embraced a wide pallate of American art in all its forms – technology, abstract, modern, impressionism, Shirey says.

The fact that he’s also shown the works of celebrities such as actress Kim Novak, singer Tony Bennett and rocker John Mellencamp – artists in their own right – has helped raise the profile of the museum. “He has so expanded the collection and enriched the exhibition schedules,” Shirey says.

For those unfamiliar with The Butler, the museum is “one of the great unsung odes, hymns and anthems to the pantheon of art,” Shirey says.

Barbara Haskell, curator of The Whitney Museum of American Art, says the museum regularly borrows from The Butler when it features major exhibitions. Edward Hopper’s “Pennsylvania Coal Town” comes to mind, as does George Luks’ “The Café Francis.”

The Butler, she continues, is “a name that people know and associate with the best quality of American art during the first half of the 20th century. People should be proud of what they have.”

Haskell says The Butler has earned a reputation of being a museum dedicated to furthering the cause of American art by generously lending its major pieces to shows all over the country. “When the best of American art gets spread around the country, it sends the message to other places that this is important.”

There are gaps in the collection, Zona acknowledges, that he would like to see filled. “I wish we had a major abstract expressionist piece – we don’t. I wish we had a major pop art piece – we don’t,” he says. “We have some examples of Andy Warhol, some examples of contemporary movements,” but no major works.

Zona’s favorite painting at The Butler is the William Merritt Chase work, “Did You Speak To Me?” from 1897. The painting depicts Chase’s daughter at his 10th Street studio in New York City, seated and turning from a series of unfinished paintings to face her father as if he had just murmured something to her. “What art historians like about this painting is that it indicates other works he had been working on in various stages,” he says, taking note of the unfinished works. “Most art historians can tell where those paintings are,” he says.

Zona reflects that The Butler stands as a testament to its original idea and purpose that engrosses and inspires artists from all over the country. “Every summer we do a themed show and invite people from the entire country and they cannot get over The Butler,” he says. “These are practicing artists.”

Moreover, Zona says he’d like to think that Joseph G. Butler Jr. would be pleased at how his museum has become such an important part of the preservation of American art history. “I was on a TV show in Chicago once,” he recalls. “The host of the show referred to The Butler as ‘America’s museum.’ I thought to myself, ‘Wow. We have a lot to be proud of.’ ”

More Butler 100th coverage

- Honoring 100 Years of The Butler (video)

- 3 Minutes With Dr. Louis Zona, Executive Director, Butler Institute of American Art (video)

- Conservation and Archiving Saves Butler’s Treasures

- Learning Is Lifelong at The Butler Institute of Art

- Business at The Butler Is Its Own Art

- The Butler Paints a Paper Trail to Display Exhibits

Pictured above: William Gropper, (1897-1977), “Youngstown Strike,” ca.1937. Oil on canvas, 20”x40”. Collection of The Butler Institute of American Art, Acquired in 1985.

Copyright 2024 The Business Journal, Youngstown, Ohio.