The Butler Paints a Paper Trail to Display Exhibits

YOUNGSTOWN, Ohio — Susan Carfano wishes that putting together an exhibit at The Butler Institute of American Art were as easy as many visitors think.

“People seem to think that the fairies show up overnight and then the show opens. It’s not that easy,” says the assistant to museum director Louis Zona. “It’s a lot of emails; it’s a lot of paperwork to get everything together and pull it together.”

At large museums, the process can take years, even decades. In that regard, Carfano says, she’s grateful that it’s as simple as it is.

“When you’re putting an exhibition together, like one we did called ‘The Artist at Ringside,’ the file we accumulated was about that big,” Zona says, his thumb and finger stretched as far as they’ll go.

“All the paperwork requesting the rights to photograph works, reproducing the works and, of course, all the insurance forms. It’s a major, major undertaking,” he continues. “For a small museum like us with a limited staff, it’s tough but we’ve done it.”

From the administrative end, putting together an exhibit is largely paperwork, Zona and Carfano agree. Elsewhere in the files are condition reports noting every detail of the work and frame, from scuffs and scratches to flaking paint, and a facility report.

“It’s everything from the construction of the building to fire systems to security. It gives you temperature and humidity readings. We do those here every week,” says The Butler’s registrar, Pat McCormick.

Once all the proper forms – largely standardized throughout the museum field, Carfano says – are turned over between museums, then comes the logistics of getting a painting from Point A to Point B. Unsurprisingly, FedEx and UPS aren’t options.

“There are art transport companies. Sometimes you’ll see a box truck in our driveway without any kind of markings at all; those tend to be the fine-arts carriers,” Zona says, noting that lending works from The Butler collection are subject to approval by the museum board of trustees.

Such trucks have air-cushioned suspensions, are climate controlled and, in some cases, the drivers are trained in art handling.

The lack of company logos serves as an added layer of security, preventing passers-by from discerning just what type of cargo sits within.

Before a piece is loaded onto the truck, it’s packed securely in a wooden crate lined with foam that holds it snugly in place. In many instances, crates are reused time and again, modified each time for the work within.

McCormick recalls one piece The Butler lent out, a piece of stained glass. For its journey, he found a crate that was previously set aside for a painting by Salem native Charles Burchfield.

“It was the perfect size except

it was half an inch too long. I cut that bit of foam and the stained

glass slipped right in,” he says. “Sometimes we might retrofit a crate because institutions don’t like to pay for crates.”

Of the process of moving art between museums, shipping is usually the costliest part, Carfano says. It’s not uncommon for prices to reach into the tens of thousands of dollars.

For a treasured piece like “Snap the Whip,” it can be as much as $40,000, she says.

“It has to go on a truck by itself because of the insurance,” she adds.

For an exhibition, that process of paperwork, condition report and shipping is repeated for each individual piece, which for larger shows such as the annual National Midyear can be hundreds of pieces.

Still, the process is usually completed within a few months. Work started in late July to begin assembling an exhibit by comic artist Jim Steranko, known for his work with Marvel and creating concept art for “Raiders of the Lost Ark” and “Bram Stoker’s Dracula.” That show is expected to open in May 2020, Carfano says.

“He wants to produce a catalogue and that could be wonderful. It would open The Butler to people who’ve never heard of us,” she says, noting that Steranko is working on obtaining some of his works from the collection of Lucasarts.

“That work starts now, but that’s a long time frame for us to what we usually do.”

Even with so much bureaucracy involved, the movement of artwork often comes down to relationships.

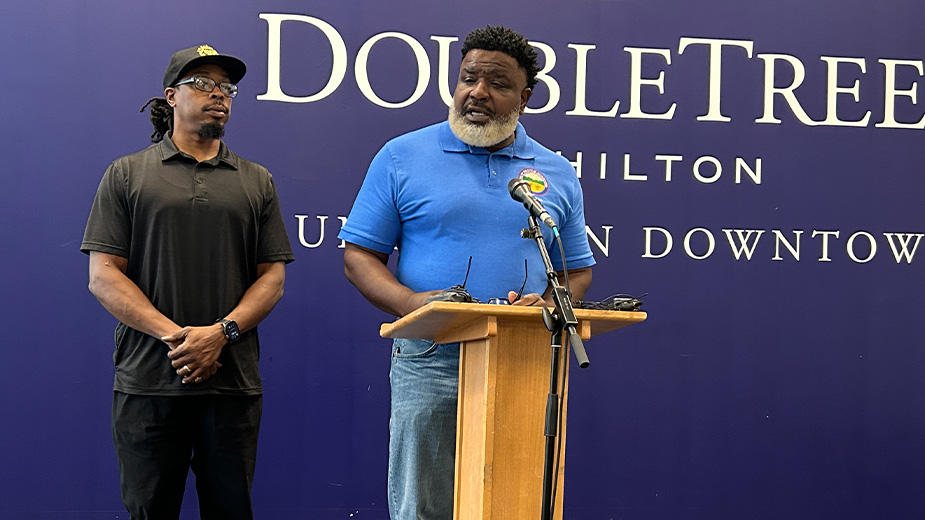

Over the course of his career, George Bolge has built three museums from the ground up – Art Museum Fort Lauderdale, the Boca Raton Museum of Art and Museum of Art-DeLand, where he currently serves as CEO – and at each stop worked with Zona to put together exhibitions and borrow art.

“He’s lent me many things from the collection, which in this day and age is very unique,” Bolge says of Zona. “That’s no little thing. Most museums in the country are hesitant about their collections and won’t bother with smaller museums. We’re just not on their radar. But The Butler has been very helpful to smaller museums getting their start around the country.”

An exhibition largely serves as a thesis, Bolge continues, centering on a theme prevalent across a wide range of works, whether by individual artists or a group.

“When you’re finished with that, you look across the country and try to find the best exemplars of it. After you find it, you write a letter to the curator or, if you’re a director, talk to the other director,” Bolge explains. “Sometimes it’s not fit for travel or it’s already out on loan or any number of things. The director and curator get together and discuss that.”

There are benefits to both sides participating in an exhibit. Because of the research a curator puts into hosting a show, it creates a clear trail of history, critiques and commentary. And for the owner, the value of his work – although not necessarily financially – increases because it’s traveled and been involved in such discussions.

“I’ve done so many shows with Lou. I’ve gotten print collections. I’ve done shows he put together that came to me and vice versa,” Bolge says. “When I’ve put a great show on, I can call Lou up and ask if he could use it. It’s always great when, as a director, you find an institution you can deal with.”

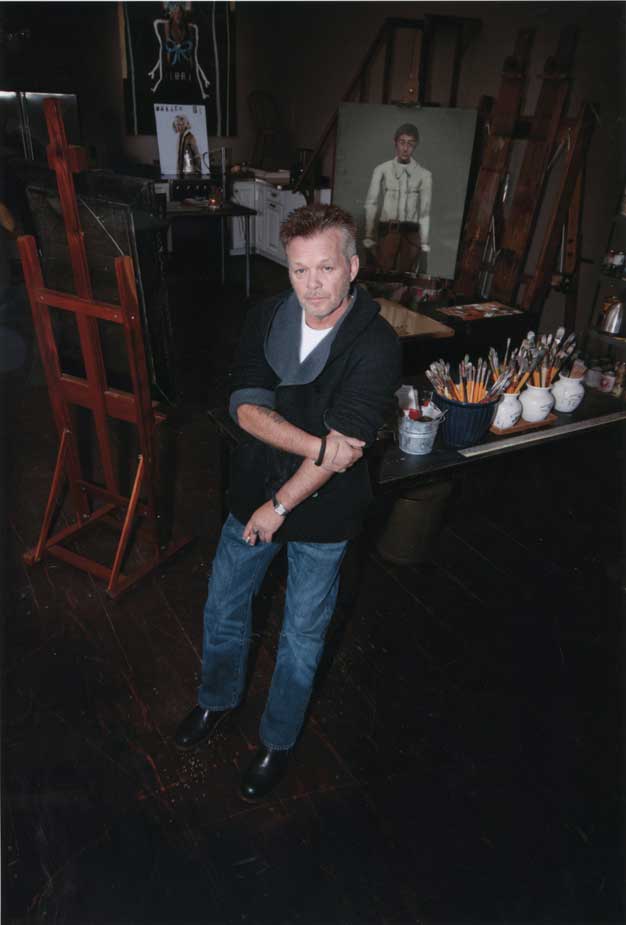

Loans and exhibitions aren’t the only way works of art move through the museum world. Since participating in the 1983 National Midyear, artist Gary Erbe has had three of his works placed in The Butler, including the commissioned “Baseball Album” and “A Gentleman’s Sport,” which the museum purchased. The third, “Lipsync,” was a partial gift-partial purchase, he says.

“My rule of thumb is that when I have a show at a museum and I see that they’ve spent money – shipping costs and the overhead of a gallery for a month or two, which can get expensive – the least I can do is give a gift to that museum,” the New Jersey-based artist says.

The Butler has also organized three career retrospectives for Erbe, celebrating his 25th, 40th and 50th anniversaries of professional work. He’s also served as a guest curator for exhibits at the institute.

Like Bolge, the artist has developed a personal connection with Zona since the two met after the 1983 Midyear. What fostered the relationship wasn’t just the museum collection, Erbe says, but how the collection is used.

“What’s important [to me] is if the museum will lend a painting when another has a special exhibition,” he says. “It’s a discussion I have with them before I even make a gift: will they lend this painting to another show I have? It’s important to me to have accessibility to the painting for exhibitions.”

It’s that accessibility, Bolge and Erbe agree, that sets The Butler

apart from other museums they’ve worked with around the world. Much of that comes down to the work Zona does.

“I’ve never met a director who’s so sensitive to the needs of contemporary artists. He’s such an open-minded man,” Erbe says.

“He believes that a museum is an institution that should give living artists the opportunity to show their work,” he continues. “The bigger a museum is, the more hostile they are toward contemporary artists. They’re just interested in the big names.”

Adds Bolge: “If you go to the Met, they give you one of 10,000 things from that artist they’ve got. … When you get to borrow something from The Butler, it’s no small thing.”

More Butler 100th Anniversary coverage

- Honoring 100 Years of The Butler (video)

- 3 Minutes With Dr. Louis Zona, Executive Director, Butler Institute of American Art (video)

- Framing History Is Butler’s Art

- Learning Is Lifelong at The Butler Institute of Art

- Conservation and Archiving Saves Butler’s Treasures

- Business at The Butler Is Its Own Art

Copyright 2024 The Business Journal, Youngstown, Ohio.