Oak Hill Brings Brain Gain to Inner City

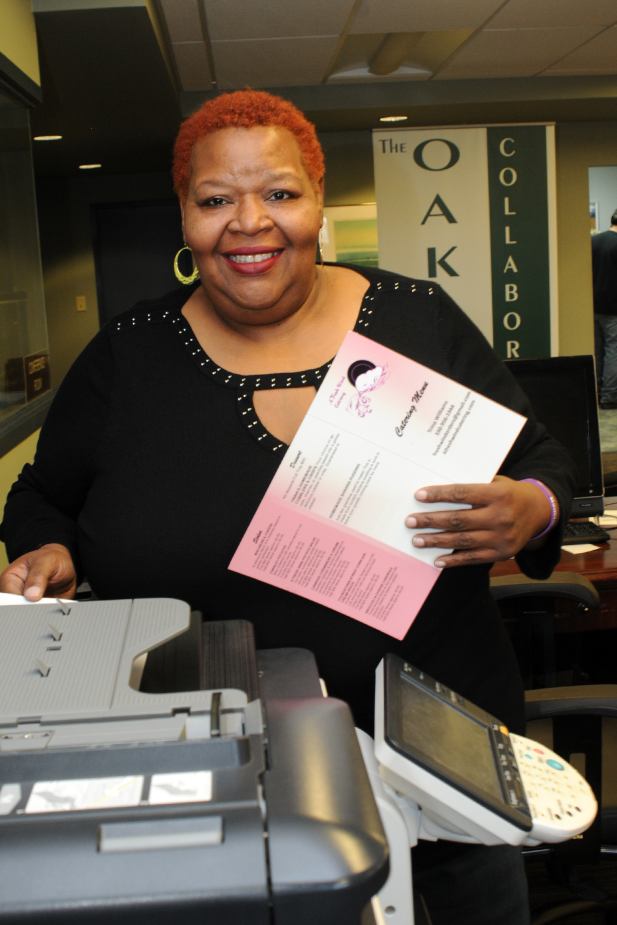

YOUNGSTOWN, Ohio — Trina Williams went from selling drugs on the streets to catering food for politicians.

Her transformation was possible through an entrepreneurial venture at the small-business incubator in the Oak Hill Collaborative where she created a catering business. She now operates the business out of the Kitchen Incubator on the city’s North Side, but continues to use the collaborative for business resources.

Williams, who started her business in her late 40s, exemplifies how people can reinvent themselves, learn new skills and contribute to the brain gain as an entrepreneur.

Before, she hustled all her life – and says she earned good grades in high school by slipping a teacher a fifth of whiskey and a carton of cigarettes under his desk. She’s been a hairdresser, sold cars, was a home-health aide at a group home, worked as a cook at the county jail, but never stopped selling.

“I always kept good jobs, but I always wanted the extra money so I could give my kids everything,” she says. “It’s what I knew, because that’s what my mom did. She sold marijuana from the house when I was growing up. She did what she had to do to take care of us.”

Williams is happy that her two daughters broke the cycle. “They knew what I was doing. I never sugar-coated anything,” she says. “I’m just glad they listened when I told them I didn’t want this life for them; not like me when my mom told me that.”

Her oldest daughter, she says, graduated as a valedictorian from Youngstown Early College. Her youngest is currently on the honor roll. Hoping to be a better role model for her daughters and tired of the streets, she quit selling drugs before she started her catering business.

Her small-business journey began in 2015, when she stopped at the collaborative to see a friend. Oak Hill Executive Director Patrick Kerrigan struck up a conversation with her and learned of her knack for cooking, and how she was selling her signature chicken-fried rolls around town.

“He brought me inside and said I needed a Facebook page. My business took off from there. I push everything out through social media,” she says.

What began as a hobby is how she makes her living today. She came up with the name, A Fresh Wind Catering, “because any wind I took out of the city doing wrong, I want to breathe it right back in. I have children. I’m not a bad person. I’ve never been arrested and I don’t have a record, but I have a platform now for good.”

City law director Jeff Limbian is one of several politicians for whom she caters. He was introduced to Williams on the campaign trail where she was serving food to the homeless.

“She insisted that I try her chicken-fried roll. I did and it was phenomenal,” Limbian says.

Limbian now hires Williams to cater his private events, adding that he can see her opening her own restaurant some day.

“She is such a dynamic person with an infectious personality,” he says. “It would be great if the city could turn out a couple more Trinas.”

Williams says her reinvention was made possible through Kerrigan, the collaborative and hard work.

“I went all the way from selling drugs to owning my own business. I’m an example of success,” she says. “I am the change.”

Kerrigan knows something about success and change. The former municipal court judge was addicted to drugs and alcohol, served time in prison for extortion and lost his license to practice law.

His fall from grace conflicted with his past persona as an altar boy where opportunities came easy – until they didn’t. “I truly believe that going away [prison] saved my life,” he says. And now he hopes Oak Hill will be a “redemption story.”

Kerrigan and retired St. Patrick Church priest the Rev. Ed Noga came up with the idea for the collaborative as part of the Oak Hill neighborhood revitalization effort. A church parishioner provided most of the funding to renovate the abandoned Forum Health building near the church.

The concept was to provide digital tools in the disadvantaged neighborhood for a better quality of life and to bridge the digital divide. The center provides free internet access, computers and printers for families unable to afford them.

Last month the collaborative marked Digital Inclusion Week with classes on 3D printing that taught adults and youth the new technology.

In one class, instructor Amy Zell explained how software can be used to create an object like a cookie cutter. Once it is created and sliced to cut using tools in the software, it is saved on a photo card or jump drive that is inserted into a 3D printer. The image passes into a roll of plastic filament that feeds into an extruder and creates the item one layer at a time. “It’s like Cheez Whiz coming out of a can that makes layers,” Zell says.

The collaborative is home to other free services such as a small-business incubator, a makerspace site that offers tools and resources to transform ideas and inventions with 3D printing and carpentry equipment, business offices with digital resources and community and group meeting space. Some office space has a minimal rental fee.

Kristen Olmi rents one of those offices. She’s had a side business of consulting for small businesses, nonprofits and politicians since 2010. When she accompanied a client to see Oak Hill, she realized she needed an office there as well. She has been there since 2015, writing grants for the nonprofit’s makerspace and program funding to keep the collaborative open.

Her day job is as a full-time grant writer for the county sanitary engineering department. She works at her Oak Hill office in the evenings and on Saturday morning, helping anyone who walks in and wants to start a business. She volunteers her services to help people prepare and file state paperwork to become incorporated and draft a business plan.

Olmi has a B.A. in political science and management from Youngstown State University and went to the University of Akron for a master’s degree in applied politics. “I took a detour and did some work in Columbus and a stint in Washington, D.C., for a short time,” she says. “But I was compelled to come back and build a career here.”

The Struthers native has a straightforward philosophy about reversing brain drain: “You can either leave and be part of the problem, or stay and be part of the solution.”

Olmi sees opportunity for entrepreneurs here, describing it as “ground zero for change.” But would-be entrepreneurs need access to capital. “We desperately need a small-business revolving loan fund. It would be nice if some foundations or corporations could put in seed money to get it started because it’s the biggest barrier to entry no matter the skill set.”

Sometimes workforce barriers are more difficult. Despite being highly educated with a judicial and college teaching background, Kerrigan was unable to get a job because of his felony record. “It’s easy to screw up and I’ve experienced it,” he says, which is why he’s committed to helping people through re-entry programs and workforce training so they have the opportunity for a second chance.

Café Augustine was created at the collaborative and is a mechanism for second chances. The Rev. Edward Beinz was in New Orleans doing recovery work after Hurricane Katrina when he came across a business called Café Reconcile that offered help and work for older adults.

Beinz returned with the idea, but changed the concept to help and employ young black men who’ve had brushes with the law. Café Augustine now operates out of the Newport Branch of the public library.

Oak Hill was a fiscal agent before the café became a nonprofit. “They were training wheels for us,” he says.

Five years later, Café Augustine has helped 350 young people by providing a model for young men to give up what they knew and learn new life skills. Workers make minimum wage and must continue to stay in school. The job teaches menu planning, sales, food preparation, advertising and shopping skills. The students run the café while the organization offers oversight and mentoring.

As companies and organizations help students learn new skills, Noga and Olmi believe people need to learn how to let go of the past.

Revamping the image the Valley has, says Olmi, will take a realization that 50 years after the steel industry’s collapse, the area is different, and change is OK.

Noga, who continues to work with Kerrigan at the collaborative and the Oak Hill Association, says “everyone knows the [region’s] problems. But stopping the exodus of young people lies in empowering our kids,” so they know that opportunities exist here and their skills are marketable.

He believes an aspect of change is to acknowledge that we have a future, but we have to claw our way back with the same hard work our parents and grandparents exhibited.

“Maybe it’s just a matter of helping young people and us to acknowledge that we do have a future. They just don’t believe it. I don’t really know the answer,” Noga says.

One thing he does know: “The future is now.”

Pictured above: Davanzo Tate strums a guitar with a 3D-printed base. With him is Pat Kerrigan, executive director of Oak Hill Collaborative.

Copyright 2024 The Business Journal, Youngstown, Ohio.