Telehealth Connects Doctors with Patients

YOUNGSTOWN, Ohio – At one point, it was the stuff of pulp science fiction novels. From the comfort of one’s home, one can push a button on his TV and a few seconds later, a doctor appears to talk over whatever ails him, maybe even make a diagnosis and write a prescription.

Today, such health care – minus robot nurses and flying ambulances, of course – is seen as the future of the industry. Through an array of services known as telehealth, physicians can connect with patients wherever either may be. It could be a video call with a specialist on the other side of the state asking questions through an online portal to figure out if a trip to urgent care is necessary or even remotely monitoring chronic conditions.

Regardless of the delivery method, it’s all done to provide patients with access to health care.

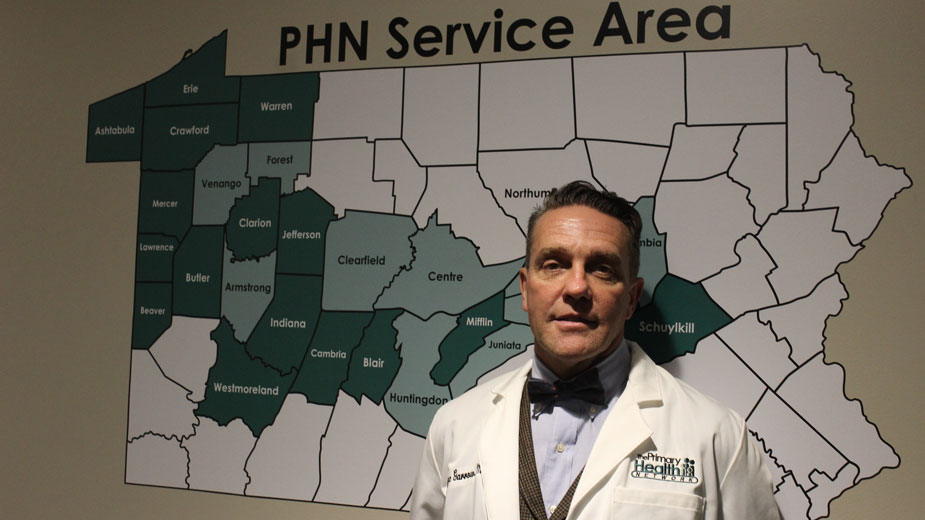

“Unfortunately, due to the economics of it, many small, rural hospitals just cannot survive. They either need to join with large systems or close,” says the chief medical officer of Primary Health Network, Dr. George Garrow. “What happens when those critical-access hospitals close? Where do patients get care? Access to primary and specialty care from an urban or tertiary facility is imperative.”

Last year, Primary Health Network, based in Sharon, Pa., was awarded a $350,000 grant from the Hospital Resources & Services Administration to implement a telehealth system to improve access to psychiatric care in Lawrence and Mifflin counties. Through the telehealth system, patients can go to Primary Health sites and talk with psychiatrists in the health system via video call. Counseling and therapy services are not available through the service.

“This is another way to provide added specialty services in the primary-care office. The behavioral health overlay on top of general medical care is critical. We can’t think of them as separate and distinct,” Garrow says. “Patients still need to go to a facility; but now we can provide services in rural communities with a doctor at another site.”

According to the American Telemedicine Association, more than half of U.S. hospitals have a telehealth program, while 90% of health-care executives say their organizations are developing or already have telehealth applications. In 2015, BCC Research projected telehealth to be a $19.7 billion business this year.

A survey by American Well found 65% of consumers want to use telehealth and 7% would consider leaving their primary care physicians for one that offers such services. According to the American Hospital Association, 76% of consumers give priority to access to treatment above meeting with doctors face-to-face.

“In 2019, we have to meet people where they are. It’s not going to a store. It’s going to Amazon. It’s having food delivered to your house instead of going out to pick it up,” says Dr. James Kravec, chief clinical officer of Mercy Health-Youngstown.

Mercy doesn’t offer video appointments, although it’s being explored. The foray by the health-care system into telehealth includes the MyChart service, an online portal for patients to communicate with doctors, schedule appointments, get lab results and request medication refills, as well as Evisit, which allows patients to type in symptoms and fill out a questionnaire to receive information back from physicians about treatments.

While efforts by Primary Health are directed toward rural areas, Mercy’s Kravec says telehealth benefits all communities because it provides easier ways for patients to connect with doctors.

“The option in a rural area might be drive 45 minutes or have no care, if there were nothing online,” he says. “Even in Youngstown, Boardman, Austintown – where there are a lot of doctors – patients don’t necessarily want to go to a busy office and wait. Even if the doctor’s on time, that’s still about an hour.”

For pediatric health, says the Ohio Hospital Association director of health economics and policy, Aly DeAngelo, being able to connect with specialists digitally can have positive effects on both children and their parents. “Kids are missing school and their lives are being disrupted, too. If they can use telehealth to get what they need, it’s a huge win for families and kids,” she says.

It’s also proven quite helpful in patients’ recovery after strokes. Since one of the biggest factors in recovery is time between occurrence and treatment, having patients be able to meet with doctors, regardless of where the physician is, is invaluable.

“Telestroke enables a prompt evaluation and recommendations regarding [clot bursting medication] administration,” said a report published by the hospital association. “Moreover, stroke neurologists can identify patients that may benefit from endovascular treatment to facilitate efficient transfer to a hospital that can provide this level of service.”

Primary Health Network’s Garrow says behavioral health is at the forefront of telehealth adoption, because it doesn’t always require the same hands-on examinations that physicians need to do.

“Psychiatry can be visual. It doesn’t necessarily need to be tactile. A lot of the visit is verbal communication and [visual] observation,” he says. “It’s hard to hear someone’s heartbeat or feel their swollen lymph nodes if you’re not right there.”

The largest barrier to widespread adoption in Ohio, the OHA’s DeAngelo says, is the lack of standardized reimbursement policies across insurance carriers. Ohio has no parity law for telehealth, meaning payers aren’t required to reimburse for the services, while Medicare and Medicaid reimbursements have strict guidelines on originating sites, distance sites, eligible services and approved providers.

“Medicare has moved in the direction of covering more telehealth services. We talk to our state Medicaid office all the time about this and they understand, especially given the opioid and behavioral-health crises, the need to open that rule and pay for more things,” she says, noting a bill in the statehouse would require parity for covering telehealth services.

For doctors, there are challenges, Kravec and Garrow agree. Medical training operates on the assumption that patients are in the room with doctors and all develop their own habits and routines when they work with patients.

“We’re taught in medical school to be physically present. So it’s a challenge to figure out how to establish that trusting relationship without being next to them physically,” Garrow says. “It’s also about establishing relationships with the staff at the remote site. … We’re relying on the staff that’s there with the patient to tell us a patient’s blood pressure is running high or they seem anxious.”

Even so, telehealth systems don’t mean a drop-off in the level of care, Kravec emphasizes.

“With the appropriate complaints and concerns from patients and [doctors] asking the appropriate questions, it can be a very effective way to deliver care,” he says. “It’s certainly not appropriate for all things. There are many complaints where you need to be able to listen to a patient, perform an exam.”

In its 2018 report, the Ohio Hospital Association measured metrics at three hospitals. In surveys done after urgent-care visits, the three hospitals reported that between 78% and 87% of telehealth patients were satisfied with their visits. The average wait time at the three hospitals ranged from four minutes and 50 seconds to nine minutes and 54 seconds.

In an 8,000-person study by the Centers for Disease Control diabetes-prevention program, there was no difference in the quality of care between in-person and telehealth visits. Meanwhile, an American Hospital Association study found telehealth programs in intensive-care units are associated with improved survival rates and shorter stays in the hospital.

Telehealth also opens up top-tier care to all communities, whether they be in rural Pennsylvania or on the other side of the world. With telehealth, anywhere that has an internet connection could potentially tap into doctors’ expertise at Mercy Health, Primary Health Network or any other medical system.

“If you think about the middle of Alaska or the middle of Nigeria, if there’s access to Wi-Fi and internet, this really opens up care to the world,” Kravec says. “Access to care means how can you get in touch with a medical provider about your health care. Is it electronically? Is it a walk-in clinic? Urgent care? An emergency room? A primary-care office? We have to have all of those available.”

Pictured: The map behind George Garrow, chief medical officer of Primary Health Network, shows its wide service area.

Copyright 2024 The Business Journal, Youngstown, Ohio.