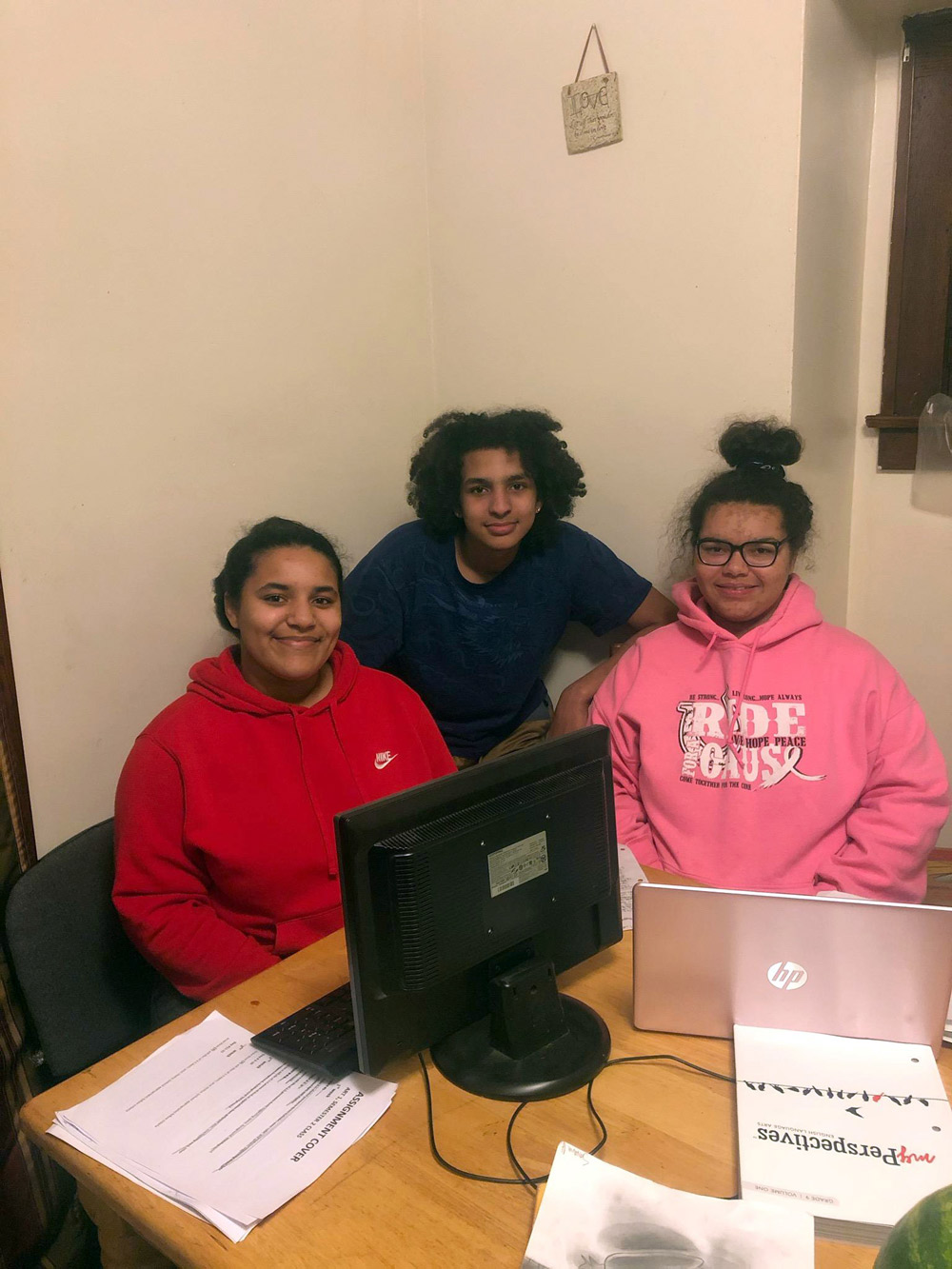

YOUNGSTOWN, Ohio – Getting three students to share one computer is a challenge, particularly during the coronavirus pandemic when students who haven’t seen their classmates in weeks would rather chat using FaceTime than focus on the course material.

That’s Leslie Tatum’s biggest challenge since schools in the state were ordered closed on March 17. Like all school districts, Youngstown City Schools had a short time to enact a plan to keep students on track and avoid brain drain. And while it’s been challenging, the district is seeing some successes.

As a certified nursing assistant, Tatum’s work is essential for her home health clients, but it means she can’t always be home to help her daughter and niece – a senior and freshman at East High School, respectively – and son, who attends Stambaugh Charter Academy. “But they work it out,” she says. They start classwork in the morning and have it done by noon so Tatum can check it after work.

“I like the idea that they can go online and pick up all of the lessons that they are missing in class,” Tatum says. “And it makes it easy for them to stay in contact with their teachers and ask for any advice.”

Initially, the district sent students home with paper packets and workbooks. Currently, all K-8 students in the district get workbooks for math, English language arts and handwriting, says Tiffaney Trella, technology integration supervisor for the district.

To supplement the lessons, teachers learned to create and post videos and have been using Google Classroom, which allows them to create, distribute and grade assignments electronically. They also conduct online class meetings with their students using Zoom and Google Meet.

In 24 hours, essentially, teachers compiled hard copies and digital assignments. They even scanned some paper documents into a digital format, says Jeremy Batchelor, principal at East High School. All digital documents and assignments are stored in a Google Drive folder that administrators can share with students and parents at their request, he says.

“There’s definitely never enough time, but I feel with the time we had, we did a great job,” Batchelor says.

Teachers have been receptive to the change, says CEO Justin Jennings. Online education includes lessons in English language arts and math as well as 35 to 45 minutes of enrichment, such as a science or art project, to help break up the day. “It’s difficult for any scholar to sit there” for hours of instruction, Jennings says.

Now, teachers are earning certifications for Google platforms through Ashland University, Jennings says, as well as all essential office personnel.

The transition from in-class teaching to online “was very fast,” and didn’t give teachers much time to prepare, says Heather Myers, who teaches language arts and seventh-grade social studies. The district’s tech department “has been fantastic” with getting teachers up-to-speed on the platforms they would be using, she says, and has offered professional development via Zoom to help them navigate the remote learning environment.

Some teachers previously had used Google Classroom, so students are familiar with the platform, she says. But while the students still receive the same academic content Myers would present in the classroom, the challenge, she says, is the lack of face-to-face support.

“We’ve been together since school started. So, we know each other’s nuances,” Myers says. “I can look at their face and body language and know [whether] they’re confused or getting frustrated.”

Being able to read those nonverbal cues is essential to a child’s education, affirms Quiana Faison, a ninth-grade English language arts teacher at Chaney High School. Faison does what she can through making videos – something that she’s never done before – and providing enough details on the assignments based on her students’ individual learning abilities, she says.

But the in-person coaching can’t be replaced, she says. During classroom instruction, she knows whom she has to prompt with questions.

“Not having that possibility for them is challenging because they knew I would be there to ask them. I can’t see what they’re thinking,” Faison says. “Not being able to do that with them and not have that verbal and nonverbal contact is something I’m currently grappling with.”

Using the software can also be a challenge for students, Myers adds. Students must navigate different tabs and screens to get the full context of the lesson. Myers shares her screen with one window, has instructions in another and the text of the assignment in another. Students also need to be able to find and use digital highlighters in the software.

Older students who are more experienced with technology handle it well, she says. “I can only imagine for younger students who haven’t had any experience what a challenge that would be for them.”

Amid the challenges, teachers are finding more parents getting actively involved in their students’ education. Several parents have contacted Faison about how to help their children log on to the online platforms and how to help with certain assignments.

Faison recently spoke with a parent who needed more information on “Romeo and Juliet” to help teach her child.

“I gave her some additional resources like SparkNotes so she could be ahead of the story for her child,” she says. “It’s really great to see parents getting involved. Now they’re seeing their work and they’re trying to keep their kids motivated.”

It’s important to let the parents know they aren’t forgotten either, says Leslie Kitchen, dean of students at Taft Elementary School. On a snowy Friday in April, Kitchen organized a parade of about 40 vehicles with faculty and staff from Taft to connect with the students and their families. So far, teachers are getting “a pretty good response” with schoolwork being completed and are following through with extra support when needed.

“Home schooling is brand new to many of our parents,” she says. “It can be overwhelming; but it can be successful if they know they have a partner in the process.”

The chief concern among parents is whether what they’re doing is enough for their students to advance. Jennings and Batchelor say that no students are at risk of being left behind.

All seniors are expected to graduate, Jennings notes. There were seven at Chaney and five at East who were at risk, but they are making up the credits, he says. “Our expectation is that all those scholars will be graduating.”

With Gov. Mike DeWine announcing April 20 that schools will remain physically closed through the remainder of the school year, the Aug. 3 date for the graduation ceremony is tentative, according to the district’s website.

In addition to supporting parents’ needs, teachers have gone to homes and stood outside to talk to their students through windows, Kitchen says. It’s particularly important for special needs students to see their teachers using hand gestures they use in the classroom to keep them engaged.

“There are really creative ways the teachers have found to get to their elementary students,” Kitchen says.

Parents also let teachers know when they don’t have access to the internet, which is the biggest concern for Chaney English teacher Faison. For some students, Google Classroom was used only in the classroom. Now, parents and guardians realize what kind of infrastructure needs to be in place at home so their students can get the education they need.

“It’s unfortunate they’ve had to figure out this way,” Faison says. “A lot of our students depend on being able to do those things at school.”

The lack of reliable hardware has affected attendance, says Trella. Teachers at Youngstown Rayen Early College are seeing a 99% attendance rate for online learning, she says. “Those are our higher kids who are college bound,” she says.

However, a kindergarten teacher in the district is seeing about 75% of her class engage in an assignment where parents record and share the videos of their children reading by using the Flipgrid platform. Some parents say they don’t have enough memory on their phones to record, Trella says.

To get a sense of the digital divide in the district, Youngstown City Schools conducted a survey asking families about their technology capabilities. Based on early numbers, 65% to 70% of families reported having access to devices, says CEO Jennings.

“We can’t tell whether that includes phones or not,” Jennings says. “That’s what we’re trying to discover.”

Some of the students already had devices they used regularly, technology supervisor Trella says. Students attending Youngstown Rayen Early College use Chromebooks and can take them home because they take classes at Youngstown State University. In other schools in the district, students in kindergarten through second grade use iPads in the classroom and students in grade three to 12 used Chromebooks, she says.

The district is working on a plan to make available as much technology as possible to other students. Laptop carts used only in the schools are being broken down to distribute based on data collected in the survey.

East High School has enough devices to cover its students. The challenge is getting them to the families. The district is working on ways to distribute the hardware while maintaining social distancing precautions. Schools in the district face the same issue with collecting workbooks.

“Quite honestly, we’re struggling because right now safety is paramount,” says East High Principal Batchelor.

Until schools collect the workbooks, administrators won’t know for sure who has completed what, he says, but daily emails from students asking when assignments are due is encouraging. The plan is to increase digital learning in lieu of the packets, he says.

Identifying the need of each of the district’s 5,300 students is the first step. Once the plan is completed, the information will be distributed to parents and to the community.

Some teachers have uploaded assignments to ProgressBook, which students and parents can check on their smartphones. Most of the teachers Trella consults with say students are using phones or even video game consoles to access their school work.

Accessing assignments on her phone has helped Leslie Tatum’s daughter, Cataria Quinn, who is a National Honors Society student and on track to be valedictorian at East High.

“They are trying to give her a laptop or computer she can use,” Tatum says, particularly for college prep programs.

However, access to technology “doesn’t equal equity” if the family lacks access to the internet, CEO Jennings says.

In its Worst Connected Cities of 2018, the National Digital Inclusion Alliance ranked Youngstown 43rd of 623 communities that lack sufficient broadband access for its residents. According to the report, of the 27,783 households in the city, 6,808 (24.5%) reported not having broadband access.

Early numbers from the district’s survey finds that 75% of households have some sort of WiFi, but Trella says, that number could be lower, because respondents took the survey online.

There are initiatives to bridge that gap, Trella says. A past government program provided free internet for low-income families at 10MB download speed, which “is not very much at all,” she says. Some households in the district have as many as six students trying to use WiFi devices at the same time.

“That’s not going to work. You can’t be drawing off of that,” she says. “It’s not just a low-income issue. It’s an everybody issue right now.”

A deal from Spectrum was offering low-income families free internet for 90 days, provided the household didn’t already have an outstanding bill with the company. That affects transient students in the district, whose families regularly move from house to house.

“When they decide not to pay their bills, they move,” Trella says. “The kids are punished because of that.”

To help connect students, the district distributed 60 WiFi hotspots. It’s also working on a plan based on the survey information. Jennings conducts weekly meetings with his cabinet and school principals to develop the plan based on their needs and observations over the last few weeks.

Looking forward, Jennings says introducing more online learning now will change education in the district.

“When we have calamities or we have snow days, [online learning] gives us the opportunity to continue educating our scholars,” he says.

Pictured at top: Leslie Kitchen waves to show Taft Elementary students they’re missed during a parade April 17 through the neighborhood.