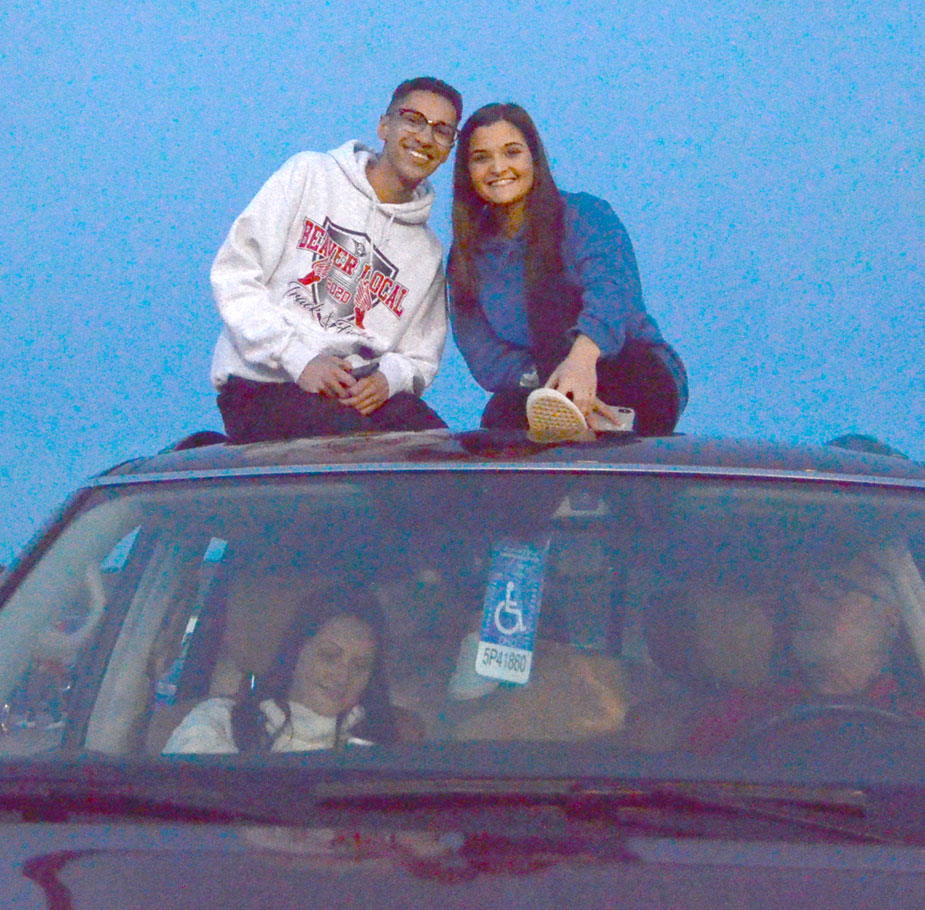

YOUNGSTOWN, Ohio — At 8:20 p.m., April 20, the lights at Beaver Local Fighting Beavers stadium illuminated the football field and the cars and trucks, driven by high school seniors and their families, gathered in the parking lot.

Students sat atop their vehicles, hung out of car windows or sat inside with their families and even their dogs. As the lights glared, students honked their horns, laughed, cheered and visited with classmates they hadn’t seen in a month or longer. First responders lined the driveway, lights flashing and sirens blaring, to honor the senior class.

Just hours before, Gov. Mike DeWine had announced that public and private schools would stay closed the rest of the school year. The light-up event, (similar ones were held at schools in East Liverpool, Wellsville and across the region) is one way the district honored the Class of 2020 as rites of passage such as prom and graduation parties are canceled.

“It’s rough. We wanted it to be a big thing, but unfortunately, it’s not. But, we’ll push through,” senior Brooke Elliott said as she painted “Beavers” and other supportive messages on the side of her car.

“It’s definitely sad. I cried a lot when I heard the news. But, at least the school is having this for us today, which is really nice,” offered senior Jaelynn Young. “I hope they’ll have a little graduation for us.”

It’s too early to say whether a formal graduation ceremony will take place, says Eric Lowe, superintendent of the Beaver Local School District. The idea of a virtual ceremony has been considered and Lowe has been in talks with administrators across Columbiana County on the subject – and districts throughout the Mahoning Valley are having the same conversation.

“I think we’re all craving to gather and see people we haven’t been able to see. That’s just human nature,” he says. “You want to be able to do those things. But you also have to be cautious of how much you’re inviting.”

With DeWine’s announcement comes questions about what school will look like at the beginning of the next school year. For now, schools will either remain closed in favor of remote learning, or reopen but have to abide by social distancing guidelines.

Superintendents in Columbiana County have met weekly via Zoom conferences to discuss both contingencies. Administrators are starting to plan how their schools will look should buildings reopen, and sharing ideas about the many variables, Lowe says.

Considerations are being given to school layouts and how to maintain social distancing, as well as starting the school year earlier, he says. Special accommodations will need to be made for students with health issues as well as those who experience online connectivity issues at home.

Administrators are also discussing the possibility of a blended model, where some students go to school while the rest attend virtually, he says. Building that model is “a large undertaking with many variables,” he says.

“Beyond learning, you got busing and food and union contracts and how districts run,” Lowe says. “It’s going to take a lot of planning and communication and guidance from a lot of stakeholders to make that most successful for students.”

Before DeWine ordered schools closed in March, districts were already planning for remote learning and working to meet students’ needs with curriculum and food, two of the top concerns among administrators, says Marie Williams, director of teaching and learning with the Columbiana County Educational Service Center.

Curriculum consultants at the ESC have worked with districts to identify resources while providing support and training for remote learning platforms, Williams says. The ESC is also working with districts to effect guidance from the Ohio Department of Education regarding grading and calendars.

Should remote learning continue into the next school year, the ESC will work with schools to help them prepare those lesson plans and provide year-round professional development, Williams says.

“We know that there’s going to be gaps,” she says. “We know that some of the material wasn’t covered and that we’re going to have to go back and make sure that this is covered before moving forward.”

Reopening the schools in any capacity presents logistical issues with keeping staff, faculty and students safe. One that’s top of mind with John Tullio, superintendent of Canfield Local School District, is getting personal protective equipment for bus drivers, faculty and staff.

“If the hospitals are having a difficult time getting this equipment, are we going to be able to get this equipment if we need it?” Tullio asks. “And are we going to have to get into a bidding war like hospitals are across the country, bidding against each other for this PPE?”

He’s also concerned about internet connectivity should remote learning continue into next year. Before the fall, the district needs to identify the students who either didn’t perform well remotely or didn’t turn in their work, he says. Any plan needs to be put in place “as soon as possible,” he says.

“We have a few students that we’re concerned about,” Tullio says.

Administrators have actively worked to contact those families, says Dave Wilkeson, president of Canfield Local’s board of education. The district has also asked the police to make wellness checks when necessary.

As for connectivity, the Canfield district distributed about 100 Chromebooks to families who needed the devices, as well as 30 WiFi hotspots, says Wilkeson, a tech consultant by trade. Wilkeson helped in the planning. He also organized STEM teachers and tech coordinators into a tactical team to work with teachers on the platforms they would be using, he says.

“We sent them out into the district and they worked with teachers,” Wilkeson says. “They got them all up and running pretty quickly.”

The biggest challenge was providing the tech to students, says tactical team member Emily Sipe, who also teaches technology classes in grades five to eight. She helped teachers digitize existing curriculum.

“There’s been a lot of thought put into how to achieve that goal,” Sipe says. “I’m impressed with everyone’s willingness to just figure it out. Nobody has been resistant.”

The district designed curriculum with more weeklong assignments, with teachers hosting video conferences with their classes once weekly. That’s allowed more flexibility with due dates, which benefits students as well as parents who work and can’t always provide support at home, she says.

Teachers have made themselves available in the evening to answer parents’ questions, Wilkeson says. The younger the student, the more critical it is that teachers talk to parents about the school work, he says.

“For some parents, it’s a challenge being at home and trying to keep the kids engaged in their school work because that’s really fallen on them instead of their teacher,” Wilkeson says.

To ensure parents aren’t overwhelmed, districts are taking family relationships and dynamics into consideration, says the CCESC’s Williams. Occupational and physical therapists with the ESC are hosting yoga sessions on Facebook and encouraging families to play board games together or go outside and take walks to enhance “social and emotional needs as well as developing those family relationships,” she says.

Like Canfield, districts in Columbiana County are reaching out to households to keep track of students who aren’t engaging in online work, about 10% to 15% of students in the county, she says. Districts reach out via phone calls, emails and Facebook messages “just to make sure that all of our kids are OK.”

Another issue is access to food. Of the 11 school districts in the Columbiana County, some in the southern part report 100% of students are on free and reduced lunches, while other districts report half of their students receive assistance.

On the day Beaver Local honored its seniors, it also held a food drive at the high school, distributing 793 bags of food, each containing a week’s worth of breakfasts and lunches for the students. The district has about 1,800 students and 45% of the families came out to pick up food, Lowe says.

The 144-square-mile rural district has many families who struggle getting to the school, he says. Beaver Local set up five remote distribution points and delivers food to homes as needed.

If there’s a silver lining in all of this, administrators agree it’s that the experience has given districts the tools necessary to not be caught off guard again.

“I’m sure it will change our ideas about budgeting and planning,” says Canfield’s Tullio. “All educators, all school districts will be better prepared for something like this in the future.”

Jo Ann Bobby Gilbert contributed to this story.

Pictured above: Seniors from Beaver Local High School arrive at Fighting Beavers stadium for a senior recognition night.