YOUNGSTOWN, Ohio – When Brandy was told by Mahoning County Judge John M. Durkin during a drug court hearing that she needed to go to residential treatment, her face turned white, and she said “No.”

The judge responded by sending her to jail.

For Brandy, it was a wakeup call. She sat in her jail cell considering the worst thing that could happen if she did go to a residential treatment facility.

She knew if she wanted custody of her daughter, she had to go to rehab.

“It was great in the end,” Brandy says. “I hated it at first, but it was great. And I needed it. It got me away from everybody that I needed to be away from.”

Brandy found drugs in the same way as many others. She was prescribed painkillers following a car accident and when she could no longer get them, she turned to street drugs and alcohol.

“I’ve had sobriety before. I was sober for seven years before, but I never worked a program,” Brandy says. Drug court, which is open to those with lower-level criminal offenses, forced her to get help.

Brandy has now been clean and sober for 13 months. She has a job and is studying for her GED, with aspirations of being promoted to a supervisor position. The people in her corner with the drug court are hoping to see her advancement become a reality, including Lauren Mathews, a vocational rehabilitation counselor, through the Ohio Bureau of Vocational Rehabilitation.

Mathews sits in the courtroom during drug court sessions to discern ways she can help those in the program get jobs. She tells Brandy she knows she can pass the GED test, which – along with the fact that she now looks healthy and professional – will lead to her getting the position she is seeking.

“One size does not fit all,” Durkin says. “So, it is critical that I as the judge and that our team conduct a good individual assessment for the person and that assessment drives their program without question. Whether they need medically managed withdrawal, residential, IOP (intensive outpatient program), we meet them where they are at. And oftentimes that recommendation from that assessment is something that they don’t want. That is nonnegotiable as it relates to their treatment.”

Durkin says some who may want outpatient treatment in order to keep working later find themselves struggling.

There can be a lot of reasons clients continue to struggle. In some cases, Durkin said there is underlying trauma that has gone unaddressed. Others have friends or family who enable their addiction.

Amy Klumpp, the Mahoning County Common Pleas Drug Court coordinator, is another member of the team, helping those going through court navigate the requirements they have been given.

“Shooting heroin is always dangerous, but then came fentanyl,” says Klumpp. “You ask any kid from the age of 25 to 40 now, [and they will tell you] they’ve lost way more friends than I have lost. It’s like we’ve lost a generation almost.”

EVOLVING TREATMENT

When Durkin started his drug court, all treatments were abstinence-based with the 12-step recovery program. He was hesitant when prescription drugs started emerging that were meant to help people kick their habits.

Klumpp points out these drugs can be expensive for the clients and in some circles still controversial.

“I was opposed to it because I didn’t understand it,” says Durkin. “There were many experts, many doctors who ultimately convinced me that it is the gold standard, but not a magic pill, and that when properly utilized along with a good recovery program, it affords the best opportunity to stay clean.”

Klumpp says one of the initial goals is to get them out of the criminal justice system. Of those who complete the program, only about 9% recidivate.

During a recent session of the Mahoning County Drug Court, a man was placed on a last-chance agreement. Minutes later, a woman smiled broadly after learning she had graduated to the next phase of the program.

Durkin took a few moments to reflect with the group on the sadness of losing one client to overdose and disappointment over two members possibly using again.

A little later, he welcomed back two people who had disappeared for a while and returned.

Durkin let those in front of him know when their appearance has improved, and talked about the good things and struggles happening in their lives.

One woman said she was tired because she is working two jobs and was afraid to tell her boss at one that she was quitting.

“Sometimes you have to think about yourself,” Durkin said. “Now is the time to be selfish and when you are working two jobs, it’s too much. I have an idea. Tell the restaurant the judge said you had to quit. I’ll be the bad guy.”

“I’m excited,” said another participant, Jennifer, when Durkin remarked she appeared to be doing better. “I haven’t had anything to look forward to in a long time. I have something to look forward to now.”

“I feel like my skepticism has been replaced by optimism,” said another man, who has been creating a design Durkin indicated will be used on a drug court T-shirt.

“‘Drug court: Where skepticism turns to optimism.’ I like it,” Klumpp added.

JUDGE’S ROLE

The success of these programs “primarily is in the relationship that a judge establishes with a client,” Durkin says. “You get to know these people, much more than a typical defendant or client. So, we do indeed celebrate their success. We celebrate their recovery, and we mourn their return to use and certainly the suffering of the family if they suffer a fatal overdose. Far too many calling hours.”

Klumpp says the program has a great team but Durkin’s engagement with the clients is critical to its success.

“It is absolutely about the judge and his willingness to get involved in these people’s lives and he’s the best in the country and maybe the world,” says Klumpp.

Columbiana County Pleas Court Judge Megan Bickerton is also making those connections. Presiding over a fledgling drug court awaiting final certification, Bickerton says the program has already paid for itself in just five months by saving lives.

She shares the story of one woman, Alissa, who failed at a prior attempt at intervention, completed the Eastern Ohio Correction Center program, but then relapsed while still on probation and was pregnant. “I just said ‘I can’t let you walk out of this courtroom. There are two lives at stake here.’”

Bickerton says Alissa was unhappy at first about those 30 days in the county jail. Then Josh Lytle of Family Care Ministries helped find the woman a place in a residential treatment center despite her pregnancy, which often precludes placement.

The baby was born healthy and the woman has moved on to phase two of the program.

“If this is all we do going forward, we’ve already succeeded,” Bickerton says. “She would tell you she was stubborn. She didn’t want to hear what I had to say. She didn’t think her issues were as bad as we saw them. (Now) she just has a whole new outlook on life. I’m so proud of her.”

Currently, Bickerton’s court has six participants, three each in phase one and phase two. Participants are required to test clean at frequent random drug screenings and meet other individual requirements to move on to the next phase.

COMMITTED TO CHANGE

A person who wants to participate “has to be fully committed,” says Bickerton. They must show up in drug court every week, get tested for drugs multiple times a week, maintain employment and go to counseling. “I think that also weeds out people who are not truly committed to getting sober and doing the drug court and taking advantage of what it has to offer. I think they must be in [the right] mindset to go on that journey to get sober.”

Despite a long record, one participant decided at this point he was ready to get clean. Now living in a sober house, he openly talks about his addiction and challenges, which leads to others finding it easier to open up.

He explained to a younger participant that while smoking marijuana may not seem like a big deal, that was exactly how he started before he spiraled into using any drug he could find.

“It’s such a personal program,” says Bickerton. “I’m invested so much in each of these participants. We talk about everything in drug court. What’s going on in their lives. What triggers they’ve had. What stressors they’ve had. What things have caused them to want to use. How they’ve stayed sober.”

Bickerton likes being proactive in helping people recover.

“It literally takes me off the bench and puts me in a different role, I just feel so much more effective in that role,” says Bickerton.

In Columbiana County Municipal Court, a long-running court program under Judge Tim McNicol helps those with misdemeanor drug-related offenses get help – hopefully before their addiction gets them into bigger trouble.

Currently there are nine participants, but there have been as many as 25 at a time. Since she started in 2017, Julie Tice, the Columbiana court’s drug court coordinator, says there have been 40 to 50 graduates, which is about 72% of those who were admitted.

“Some people don’t make it, but I think we count our successes more than we do our failures,” says McNicol, noting while they do not keep track of recidivism numbers, the court sees very few of the graduates back in court.

A team of people from three counseling groups – Family Recovery, The Counseling Center and On Demand – helps support drug court participants.

“For the most part, when they relapse, they’re apologizing to us over and over because they feel so bad that they let us down,” says Tice. “So, we’ve got to let them know that we get it and we just have to come up with a way to get them back on track. Our goal is not to put people in jail. It is to see them complete the program.”

While staying out of jail can be a motivator, McNicol says first-time offenders who complete the program can have their charges expunged.

For others, getting custody of their children is a motivator. Tice has been known to go to custody hearings in juvenile court to support clients during a stressful time and vouch for them.

“Just having Julie (Tice) go to those as a support person and knowing that she’s there and that we care and we’re following what goes on in their lives, I think helps reinforce to them that we’re on their side and we want to see them succeed,” McNicol says.

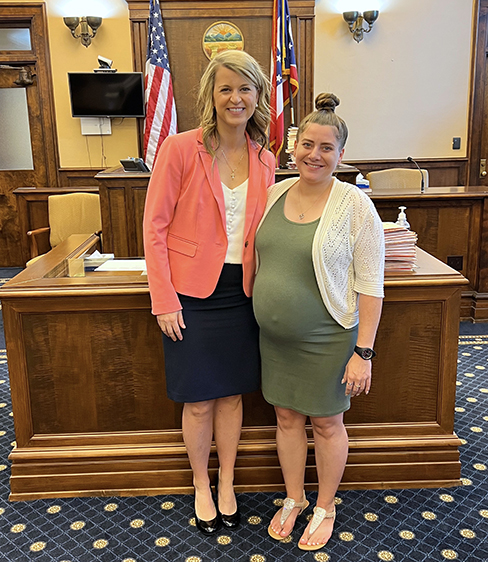

Pictured at top: Mahoning County drug court coordinator Amy Klumpp and Common Pleas Judge John M. Durkin lead a team that helps drug court clients.