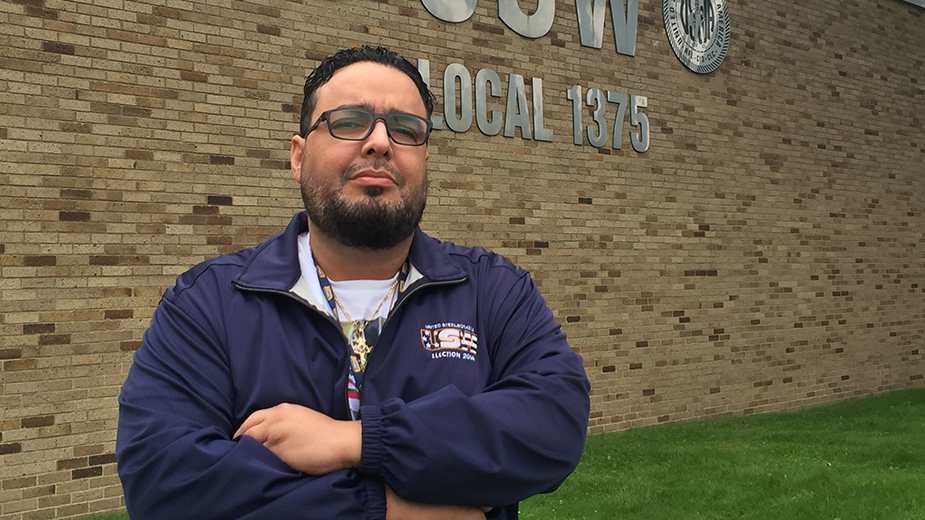

YOUNGSTOWN, Ohio – Jose Arroyo, the United Steel Workers’ staff representative for the region, takes a short break from a midterm bargaining session with managers from the Wheatland Tube operations in Warren.

Negotiations are likely to go on until the middle of the afternoon, he says, as he steps away from a table where approximately 10 others are seated at the USW Local 1375 hall in Warren.

At issue is a $40 million investment that Wheatland Tube plans for its Warren plant. In this case, it’s a highly automated warehouse that would require fewer workers in the future as the company adapts to the ongoing drought in the labor market.

“We love when new capital investment comes in,” Arroyo says. “But this gets into a larger conversation. At some point, the lack of manpower is going to invigorate an effort by companies to automate systems that we haven’t seen since the 1980s and ‘90s.”

Some labor unions have made important gains over the past several years. Workers United, for example, now represents more than 1,100 at TJX HomeGoods’ distribution center in Lordstown. It is also leading the campaign to organize Starbucks coffeehouses throughout Ohio.

Then there are reminders that tensions between labor and management remain high, as the United Auto Workers emboldens its efforts to win big contracts with the Big 3 automakers and their electric-vehicle battery joint ventures.

‘RECORD CONTRACTS,’ FEWER WORKERS

The bargaining sessions underway at the USW Local 1375 union hall reflect the current trade offs facing organized labor in the Mahoning Valley and elsewhere, Arroyo says.

On one hand, the Steelworkers union has of late bargained “record” agreements for its membership, Arroyo says. Companies in this market are more willing to consider proposals from locals because they want to retain and attract experienced and skilled workers to fill much-needed positions. Inflation has also placed pressures on the market, he adds.

“The good thing about a fair labor market is that it gives us a lot of bargaining power at the table,” Arroyo says.

One downside, however, is that the market has also empowered many companies to step up investments in automation, reducing the need for additional workers as employees retire – the very scenario playing out at Wheatland Tube, Arroyo says.

“I see other companies looking to automate as attrition takes hold,” he says. Even service positions have been replaced with pay kiosks at fast-food restaurants or self-checkout lines at grocery stores.

But for now, Steelworkers union members have recently enjoyed hefty bargaining agreements that in any other market would have triggered much more pushback from employers, Arroyo says.

“It’s not just hitting the most profitable of companies. The market is hitting entry-level pay and companies that have not historically given those types of raises,” Arroyo says.

The union recently negotiated what he termed a “record” contract for workers at Hynes Industries in Austintown. “The company and union have worked together,” Arroyo emphasizes. Moreover, Hynes has since included additional wage enhancements above and beyond the pact after it was signed.

Another strong agreement was ratified for warehouse workers in Hudson for a national company that was having its share of troubles.

Employees represented by the Steelworkers union at Universal Stainless in North Jackson, for example, were offered pay increases midway through their existing contract, Arroyo says.

Steelworkers at Datco Manufacturing in Boardman, Howmet in Niles, and Commercial Metal Forming in Youngstown have also recently won generous agreements.

“That doesn’t happen if you don’t have leverage,” Arroyo says. “They can’t find workers.”

Industrial maintenance workers are in especially high demand, he says. “I don’t think a month goes by without me being contacted by an employer saying we’d like to sit down to increase maintenance pay.”

McDONALD STEEL CORP.

Even the bleak announcement in July that McDonald Steel Corp. would shutter its 14-inch hot mill affecting approximately 80 workers still engenders hope among the USW, Arroyo says.

The mill is running out its contractual work and those employees will lose their positions when it’s completed. The USW, along with Teamsters Union Local 377, negotiated enhancements for worker separation pay.

What is unusual, Arroyo says, is that the company has agreed to keep the collective bargaining agreement open for the next three years and ensure recall rights to these workers.

“We’ve been told by the company that this is not the end of McDonald Steel,” Arroyo says. “Their hope is to reinvent themselves.”

Jim Grasso, president and CEO of McDonald Steel, affirms that an agreement with the unions was reached. “The bargaining is completed and agreed to,” he says. He declined to comment on other matters at the company.

Arroyo says he’s negotiated nine plant closures over his more than eight years as a USW staff member. “This is the first time where the company was willing and eager to leave open the agreement and not want to close it out and sever,” he says. “Whether or not the separation is permanent, we’ll find out in the next three years.”

Union representation at McDonald Steel is unusual in that workers share dual membership in the USW and the Teamsters, Arroyo says. Both unions are signatories to a single collective bargaining agreement with the company.

The Steelworkers also represent employees at Brentwood Originals, a decorative pillow manufacturer in Youngstown; chemical plants in Ashtabula; tire production workers; oil workers; education employees; and even gravediggers.

“It’s not just Big Steel anymore,” Arroyo says.

ORGANIZING EFFORTS

Indeed, organizing initiatives have expanded to industries that were once never considered ripe for unionization. Coffee shops, museums, retailers, nonprofits and universities have organized.

In January, the U.S. Department of Labor Bureau of Labor Statistics reported that in 2022, union membership across the United States increased by 273,000 to 14.3 million. The union membership rate of the entire workforce stood at 10.1%, down from 10.3% in 2021, failing to keep pace with overall job growth.

In Ohio, unions have emerged as an effective force, especially in the wake of a special election held in August, says Bill Padisak, president of the Mahoning Trumbull AFL-CIO.

He says organized labor’s successful campaign to defeat Issue 1 – which would have mandated that any amendment to the state constitution would require at least 60% of the popular vote instead of a simple majority – proved that its role has not diminished.

“It’s refreshing to see from around the state how many people have a positive view of unions,” he says.

After the defeat of Issue 1, Padisak reports unions representing more than 1,000 people joined the local chapters of the AFL-CIO.

“These were unions that previously did not participate in the labor council,” he says.

According to the Columbus office of the AFL-CIO, Mahoning and Trumbull counties are home to 26,227 union members and retirees, Padisak says. In Ohio, some 641,000 workers in the public and private sectors belong to unions, or 12.8% of the state’s workforce, according to BLS data.

Moreover, unions have sought additional organizing opportunities across Ohio, especially in the service sector.

“Retail stores, Starbucks – these are companies that were never organized before,” Padisak points out.

Workers United, an affiliate of the Service Employees International Union, has organized approximately a dozen Starbucks coffee houses in Ohio, says the union’s regional vice president.

“There’s always an opportunity to organize,” says Carlos Ginard, vice president of the Chicago and Midwest Regional Joint Board of Workers United. Efforts to arrive at a national contract with Starbucks proved futile, he says, so Workers United has focused on organizing store by store. “That’s pretty much how it’s working,” he says

At present, there are no campaigns to organize baristas in the Mahoning Valley, Ginard says, although the union has succeeded in securing contracts for Starbucks workers in the Cleveland and Columbus areas.

Ginard says the Mahoning Valley is fertile ground for organizing other sectors, such as the region’s potential for expanding distribution and warehousing activity.

Workers United represents more than 1,100 workers at the new TJX HomeGoods distribution hub in Lordstown, Ginard says. “We already had a relationship with TJX,” he says, through previous organization activities at other hubs in the Midwest.

TJX employees in Lordstown ratified a three-year contract in June 2021 after the $170 million distribution center opened.

The contract sets the table for organizing other distribution centers in or around the Lordstown area, according to Ginard. As this industry grows, so too does the potential for building union membership, he says. Workers United represents between 30,000 and 40,000 distribution workers throughout the country.

“Lordstown is a union area that has always had a lot of potential and we want to be part of that,” Ginard says. “We’re very excited about the possibilities and to also grow at TJX HomeGoods,” he says.

UAW TAKES TOUGH STAND

Meanwhile, the United Auto Workers union is locked in bargaining sessions with Ultium Cells LLC, a joint venture between General Motors Co. and Korea-based LG Energy Solution that manufactures electric-vehicle battery cells at its $2.3 billion plant in Lordstown.

Last December, workers there voted overwhelmingly to join the UAW after an election administered by the National Labor Relations Board was held at the plant. On Aug. 24, Ultium and the UAW announced a retroactive agreement whereby hourly wages were increased by an average of 25%.

“The UAW Local 1112 members working at Ultium Cells deserve this increase for being essential in getting the plant up and running,” said Josh Ayers, UAW Local 1112 chairman, in a statement.

“While an entire ‘first’ agreement is being negotiated, the committee is still hard at work in bargaining working conditions, health and safety, seniority rights, addressing other issues raised by the membership and future wage increases throughout the term of this agreement.”

Newly elected UAW President Shawn Fain has been vocal about EV battery workers at plants affiliated with the Big 3 automakers receiving higher wages and additional safety protections.

He and others – particularly U.S. Sen. Sherrod Brown, D-Ohio – have agitated for GM, Ford Motor Co. and Stellantis to fold JV battery workers into any national contract with the UAW. The national contracts between the Big 3 and the UAW expire Sept. 14.

But since Ultium Cells is an entity separate from GM, the battery-cell company argues that it should not be part of a national labor contract with the automaker and the UAW.

Alex Eom, acting president at Ultium, said in a letter to Brown dated Aug. 3 that the company does “not see a viable legal or practical path to place Ultium Cells-Ohio into the General Motors national agreement.”

Fain and the UAW have dug in. Buoyed by significant profits by the Detroit automakers, Fain and the union are demanding higher wages, an end to the tier system and a 32-hour work week for 40 hours pay. Much of these demands, he has said, are in place to make up for concessions the UAW has made in previous negotiations. In late August, union membership authorized a strike against the automakers if an agreement isn’t reached.

The wild cards in these negotiations are the battery plants, says John Russo, visiting scholar at the Kalmanovitz Initiative for Labor and Working Poor at Georgetown University.

“They want to organize these plants,” Russo says. “That’s the difficulty and there’s no clear indication as to how it’s going.”

Russo suspects there might be some give in the national contracts in exchange for assurances to organize battery plants. “Will they get less for their membership in the end in order to get organized in the other plants?” he asks. “That’s the quid pro quo.”

Ultium’s Lordstown plant is the first to negotiate with the union. So there’s pressure to achieve a solid contract that serves as a template for future labor agreements in the EV industry, Russo says. “Ultium is the pace setter.”

Fain has been especially vocal about improving working conditions and pay at the Ultium plant in Lordstown. In May, the UAW chief visited workers from the plant. He objected to low starting wages – calling them “shameful” during a live Facebook broadcast from Local 1112’s union hall nearby. At that point, entry-level workers at Ultium were earning $16.50 per hour, he said.

Fain also called into question workers’ exposure to hazardous materials. On Aug. 23, OSHA said it is investigating a chemical spill caused by a pipe rupture at the Ultium plant that temporarily shut down production.

“Our investigation into the cause of the spill is ongoing and area operations were paused until cleanup was complete. And the entire surrounding area has been inspected for damage and deemed safe,” Ultium’s spokeswoman said in a statement.

Russo observes that the Fain’s tough stance is in part because he’s the UAW’s newly elected president, winning by a slim margin in March. “These negotiations become important in that he doesn’t appear like milquetoast or a pushover,” he says.

A bargaining agreement with the UAW at Ultium could set the tone for the burgeoning EV industry, Russo says. “There is a sense that they need to get negotiations under their belt, get good contracts which they can organize around future automobile subcontractors and battery suppliers.”

Pictured at top: “The good thing about a fair labor market is it gives us a lot of bargaining power,” Jose Arroyo says.