WARREN, Ohio – Wiley Runnestrand looks on as a large yellow excavator extends its arm and picks apart the third floor of what was once St. Joseph Riverside Hospital in Warren. Separated piles of concrete and steel 10 feet high are studded throughout the former parking lot, as one of the city’s most ambitious demolition projects nears the finish line and reduces the building to rubble.

Razing the eyesore – a condemned structure that has sat vacant along the Mahoning River for more than two decades – is a milestone for the city. Still, questions nag Runnestrand. What would be the legacy of this property? What would be left for the community 10 years from now?

“It’s a pretty rare opportunity to take 15 acres of riverfront property in the heart of the city and imagine something that takes the community to the next level,” Runnestrand says as he watches heavy machinery tear the massive building apart piece by piece. “We want to give the city an idea of what could be.”

NEW APPROACH

His answer was to engage the Kent State University College of Architecture and Environmental Design and enlist students to envision uses for the site. The idea was to work with the city administration and community stakeholders to produce several options for redevelopment.

This approach not only provides fresh ideas for the former St. Joe’s property, it also signals a generational shift in thinking that unlocks new potential for the entire Mahoning Valley, says Runnestrand, who is in his mid-30s.

“You’re at a point where you can reinvent yourself,” says Runnestrand, who along with Michael Martof, also in his 30s, and businessman Chuck George are principals of Sapientia Ventures LLC, a venture capital group formed last year that seeks to invest in new development opportunities. The partnership also owns Greenboard IT, an electronics recycling company in Warren.

Sapientia has no financial stake as of now in the former St. Joe’s site, Runnestrand emphasizes. Instead, Sapientia donated $2,000 to KSU’s architectural college that is earmarked for student community projects such as the Warren initiative. The venture capital firm invested another $3,000 to cover the costs of materials for a dozen students to present their design projects and to publish a book that features detailed specifications on all of the students’ work.

Runnestrand says he and his partners understand that the successful redevelopment of the site could set a new standard for reinvigorating older communities across the Mahoning Valley. This in turn could create a draw as the local economy undergoes its own transformation.

“We’re at a point where a lot of people want to come in and make investments,” Runnestrand says.

He cites as catalysts for regional growth Foxconn’s $230 million purchase of Lordstown Motors Corp.’s plant last year, Ultium Cells LLC’s new $2.3 billion battery-cell manufacturing plant in Lordstown and initiatives underway at Brite Energy Innovators in Warren and the Youngstown Business Incubator.

The St. Joe’s project presents a perfect opportunity to attract multiple ideas to the table, Runnestrand says. Previously, he worked in the fundraising department at KSU’s architectural college, where he established an association with Bill Willoughby, associate professor and design innovation fellow at Kent.

After Runnestrand left that job, he and Willoughby continued to work together.

“I go to Bill and pitch the projects,” he says. “I know just enough about architecture and enough of the community officials to suggest projects that could make a good fit.”

Nearly 10 years ago, Runnestrand and Willoughby recruited students to submit design ideas for the successful redevelopment of Phelps Street in downtown Youngstown. The same strategy is now being applied to the Warren site, he says.

“Where I see Kent State playing a role is presenting a treasure trove of ideas for a site that we don’t know quite what to do with yet,” he says.

STUDENTS TAKE THE LEAD

The force behind KSU’s contribution is Willoughby, whose students have worked on projects in Youngstown, Garretsville, Sandusky and Erie, Pa.

“We’ll look at opportunities to take the skills that we want our students to apply and work with community partners,” he says. “We like to get involved where there’s no architect involved yet. We like to get involved in creating a vision for a community that will later lead to a project emerging.”

Among the first local projects he helped direct was the Phelps Street corridor. That effort resulted in the city adopting portions of students’ ideas and hiring a professional design team to execute the project, closing the street to vehicular traffic and converting it into a pedestrian walkway leading directly to the Youngstown Foundation Amphitheatre.

“What we’re trying to do is offer ideas,” Willoughby says. “We’ll try to offer not just a vision, but multiple ones. We had 40 to 50 students offering ideas. It was a pretty extensive project over a couple of years.”

Willoughby has applied the same formula to the Warren St. Joe’s site. In this case, 12 of his third-year architecture students were presented last semester with a challenge to come up with structural and environmental designs for repurposing the property.

Student concepts ranged from creating a nature center to a park and a mixed-use space.

Nelson Logan, a third-year architecture student, says the central theme of his plan is the construction of a food hall at the site. “It’s similar to a food court, but it’s made exclusively for small, local businesses,” he says. “It could either be a permanent place for these businesses or a type of incubator.”

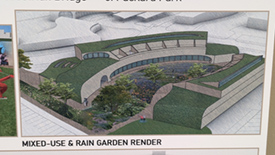

Logan’s design elements for the building include an exterior industrial appearance with a stepped “green” rooftop covered in vegetation but also suitable for outdoor dining.

“We started the project looking at all aspects of Warren to really understand the community,” he says. One of the needs that stood out was that the area is considered a food desert. His creation of a food hall is based on the region’s cultural heritage. A garden that contributes to the food hall is also incorporated into his design.

Another important element to Logan’s design – indeed, this factors prominently in all of the students’ submissions – is the Mahoning River. Part of the plan is to build a walkway over the river to connect it with Packard Park.

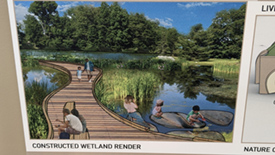

Molly Zwack says the environment heavily influences her project, what she calls the Mahoning Interdisciplinary Revitalization and Sustainability Complex. “Since the site borders along the Mahoning River, I wanted to use it as the main inspiration.”

After she spoke to members of the community and conducted preliminary research, Zwack says she found that the river serves as a natural dividing line between the eastern and western sides of the city. “I wanted to reimagine how the river could become a joining factor and an attractor for visitors,” she says.

A focus of her plan is to build a nature center on the northern portion of the site near the river where patrons could interact with the environment and learn more about the natural history of the area. The center would be designed with a green roof and living wall, while the surrounding area is punctuated with walking paths.

Zwack’s plan also calls for an art and growing center, as well as an observatory near the nature center. “I wanted to explore how Steam [science, technology, engineering, art and mathematics] could be incorporated into the neighborhood.”

The second portion of her plan envisions a mixed-use development toward the middle of the site that integrates natural features such as a vegetation roof into the design. “It would have shops on the bottom and then above it will be affordable apartments,” she says. “I’m hoping it will target the younger generation that want to move into Warren.”

An important component of the student projects was interacting with Warren elected officials, administrators, planners and residents of the community, Zwack says. “We got all of their feedback from what they would like to see in Warren.”

Kent State’s Willoughby says that the objective is not necessarily to present a winning design that the city would adopt. Rather, it’s to help launch a discussion of potential uses and perhaps leverage these ideas for future funding through public or private sources.

“I think it’s an important learning opportunity,” he says.

Willoughby is also co-teaching a course this spring that will examine the city of Warren in a more comprehensive sense that includes mapping and identifying potential areas of development across the city.

“We will create something that we call an atlas of opportunity,” Willoughby says. “We’ll be looking at things that we think present Warren for growth and certainly transformation.” The hope is that this project could lead to the creation of a master plan for the city’s future, he adds.

CITY EMBRACES THE PLAN

From the start, Warren officials were enthusiastic about engaging Kent State students in the St. Joe’s project.

“We thought it was a wonderful idea to get young brains thinking outside the box,” says Mike Keys, director of community development. City officials met with the students – first at Brite Energy and then at the demolition site.

Keys cautioned that the project needed to be sensitive to the western Warren neighborhood that borders the St. Joe’s property.

“They don’t want certain things for their neighborhood; so they were really concerned,” he says. “In a lot of ways, I think this helped soothe their minds about what was going to happen there – that we’re not rushing in to anything and that we’re considering all kinds of ideas from residential to green space – even museums.”

The goal, Keys says, is to continue the city’s relationship with Kent State and apply this development strategy to other parts of Warren. Among these targeted areas could be the Golden Triangle – an industrial sector mostly in Howland Township that also rests in the city. Other areas include sections just north of Courthouse Square downtown.

“These students come in from a different outlook and a different perspective on things,” Keys says.

The first step was to finally remove the blighted St. Joe’s building, which after more than 25 years had become graffiti-laden and dangerous. It wasn’t until 2019 that the state of Ohio took possession of the property after a foreclosure action. In 2021, the state transferred the former hospital to the Trumbull County Land Bank. In April of last year, the state allocated $3.4 million in brownfield grant money to raze the structure. Demolition began in November.

“The demolition of the hospital was the No. 1 priority of my administration,” says Mayor Doug Franklin. “Having that project started and near completion is easily the biggest accomplishment of 2022 – probably of my whole tenure.”

Franklin praises the work of the Kent State students and their designs. “Those students – they’re not constricted by budgets and can think freely,” he says. “It’s pretty impressive. What we plan to do afterward is very exciting.”

LOOKING BEYOND ST. JOE’S

For venture capital firms such as Sapientia, these projects unleash the potential for future investment across the entire Mahoning Valley, says Sapientia partner Mike Martof. “It’s not just about public amenities; it’s about economic use of the space,” he says.

Martof emphasizes that Sapientia’s efforts in their projects is to engage all of the stakeholders. “A big part of it too is making it open source, so that we’re not the only developer doing something,” he says. “Obviously, we’re invested in Warren. But we want other people invested in Warren as well.”

The St. Joe’s site presented an appealing project for Sapientia, Warren and the partnership with KSU, says Sapientia’s Chuck George.

A key element is attracting younger people to the community and to develop cities that accommodate their needs, he says. George, who began his professional career as an accountant in the 1970s, is today the president and CEO of Hapco and Strangpresse.

“I remember in the 1960s what this place looked like,” he recalls, noting that his vision of the future would be clouded by those images. “That’s not what people today want. We need to get some fresh, new ideas, and these students are talented. I think the revitalization of the area is going to be very dependent upon that.”

Pictured at top: Chuck George and Wiley Runnestrand, partners in Sapientia Ventures.